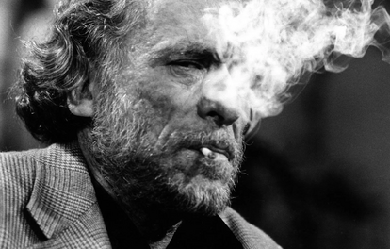

Henry Charles Bukowski (born Heinrich Karl Bukowski; August 16, 1920 – March 9, 1994) was an American poet, novelist and short story writer. His writing was influenced by the social, cultural and economic ambience of his home city of Los Angeles. It is marked by an emphasis on the ordinary lives of poor Americans, the act of writing, alcohol, relationships with women and the drudgery of work.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Evidence suggests that Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation. Considered an eccentric by locals, she developed a penchant for white clothing and was known for her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, to even leave her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most friendships between her and others depended entirely upon correspondence.

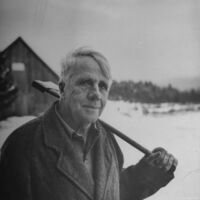

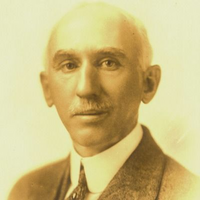

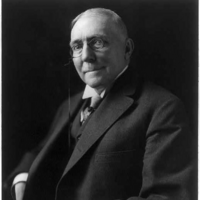

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 – January 29, 1963) was an American poet. His work was initially published in England before it was published in the United States. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech, Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New England in the early 20th century, using them to examine complex social and philosophical themes. Frequently honored during his lifetime, Frost is the only poet to receive four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. He became one of America’s rare “public literary figures, almost an artistic institution”. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1960 for his poetic works. On July 22, 1961, Frost was named poet laureate of Vermont.

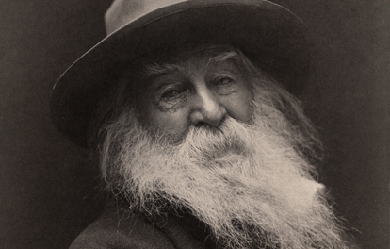

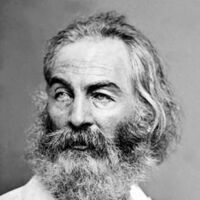

Walter Whitman (May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the father of free verse. His work was controversial in his time, particularly his 1855 poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its overt sensuality.

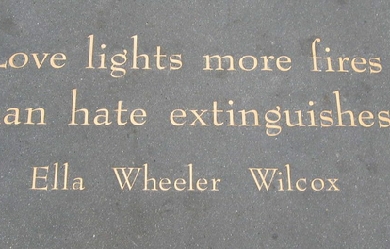

Ella Wheeler Wilcox (November 5, 1850– October 30, 1919) was an American author and poet. Her best-known work was Poems of Passion. Her most enduring work was “Solitude”, which contains the lines, “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; weep, and you weep alone”. Her autobiography, The Worlds and I, was published in 1918, a year before her death. Biography Ella Wheeler was born in 1850 on a farm in Johnstown, Wisconsin, east of Janesville, the youngest of four children. The family soon moved north of Madison. She started writing poetry at a very early age, and was well known as a poet in her own state by the time she graduated from high school. Her most famous poem, “Solitude”, was first published in the February 25, 1883 issue of The New York Sun. The inspiration for the poem came as she was travelling to attend the Governor’s inaugural ball in Madison, Wisconsin. On her way to the celebration, there was a young woman dressed in black sitting across the aisle from her. The woman was crying. Miss Wheeler sat next to her and sought to comfort her for the rest of the journey. When they arrived, the poet was so depressed that she could barely attend the scheduled festivities. As she looked at her own radiant face in the mirror, she suddenly recalled the sorrowful widow. It was at that moment that she wrote the opening lines of “Solitude”: Laugh, and the world laughs with you; Weep, and you weep alone. For the sad old earth must borrow its mirth But has trouble enough of its own She sent the poem to the Sun and received $5 for her effort. It was collected in the book Poems of Passion shortly after in May 1883. In 1884, she married Robert Wilcox of Meriden, Connecticut, where the couple lived before moving to New York City and then to Granite Bay in the Short Beach section of Branford, Connecticut. The two homes they built on Long Island Sound, along with several cottages, became known as Bungalow Court, and they would hold gatherings there of literary and artistic friends. They had one child, a son, who died shortly after birth. Not long after their marriage, they both became interested in theosophy, new thought, and spiritualism. Early in their married life, Robert and Ella Wheeler Wilcox promised each other that whoever went first through death would return and communicate with the other. Robert Wilcox died in 1916, after over thirty years of marriage. She was overcome with grief, which became ever more intense as week after week went without any message from him. It was at this time that she went to California to see the Rosicrucian astrologer, Max Heindel, still seeking help in her sorrow, still unable to understand why she had no word from her Robert. She wrote of this meeting: In talking with Max Heindel, the leader of the Rosicrucian Philosophy in California, he made very clear to me the effect of intense grief. Mr. Heindel assured me that I would come in touch with the spirit of my husband when I learned to control my sorrow. I replied that it seemed strange to me that an omnipotent God could not send a flash of his light into a suffering soul to bring its conviction when most needed. Did you ever stand beside a clear pool of water, asked Mr. Heindel, and see the trees and skies repeated therein? And did you ever cast a stone into that pool and see it clouded and turmoiled, so it gave no reflection? Yet the skies and trees were waiting above to be reflected when the waters grew calm. So God and your husband’s spirit wait to show themselves to you when the turbulence of sorrow is quieted. Several months later, she composed a little mantra or affirmative prayer which she said over and over “I am the living witness: The dead live: And they speak through us and to us: And I am the voice that gives this glorious truth to the suffering world: I am ready, God: I am ready, Christ: I am ready, Robert.”. Wilcox made efforts to teach occult things to the world. Her works, filled with positive thinking, were popular in the New Thought Movement and by 1915 her booklet, What I Know About New Thought had a distribution of 50,000 copies, according to its publisher, Elizabeth Towne. The following statement expresses Wilcox’s unique blending of New Thought, Spiritualism, and a Theosophical belief in reincarnation: “As we think, act, and live here today, we built the structures of our homes in spirit realms after we leave earth, and we build karma for future lives, thousands of years to come, on this earth or other planets. Life will assume new dignity, and labor new interest for us, when we come to the knowledge that death is but a continuation of life and labor, in higher planes”. Her final words in her autobiography The Worlds and I: “From this mighty storehouse (of God, and the hierarchies of Spiritual Beings ) we may gather wisdom and knowledge, and receive light and power, as we pass through this preparatory room of earth, which is only one of the innumerable mansions in our Father’s house. Think on these things”. Ella Wheeler Wilcox died of cancer on October 30, 1919 in Short Beach. Poetry A popular poet rather than a literary poet, in her poems she expresses sentiments of cheer and optimism in plainly written, rhyming verse. Her world view is expressed in the title of her poem “Whatever Is—Is Best”, suggesting an echo of Alexander Pope’s “Whatever is, is right,” a concept formally articulated by Gottfried Leibniz and parodied by Voltaire’s character Doctor Pangloss in Candide. None of Wilcox’s works were included by F. O. Matthiessen in The Oxford Book of American Verse, but Hazel Felleman chose no fewer than fourteen of her poems for Best Loved Poems of the American People, while Martin Gardner selected “The Way Of The World” and “The Winds of Fate” for Best Remembered Poems. She is frequently cited in anthologies of bad poetry, such as The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse and Very Bad Poetry. Sinclair Lewis indicates Babbitt’s lack of literary sophistication by having him refer to a piece of verse as “one of the classic poems, like 'If’ by Kipling, or Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s ‘The Man Worth While.’” The latter opens: It is easy enough to be pleasant, When life flows by like a song, But the man worth while is one who will smile, When everything goes dead wrong. Her most famous lines open her poem “Solitude”: Laugh and the world laughs with you, Weep, and you weep alone; The good old earth must borrow its mirth, But has trouble enough of its own. “The Winds of Fate” is a marvel of economy, far too short to summarize. In full: One ship drives east and another drives west With the selfsame winds that blow. ’Tis the set of the sails, And Not the gales, That tell us the way to go. Like the winds of the sea are the ways of fate; As we voyage along through life, ’Tis the set of a soul That decides its goal, And not the calm or the strife. Ella Wheeler Wilcox cared about alleviating animal suffering, as can be seen from her poem, “Voice of the Voiceless”. It begins as follows: So many gods, so many creeds, So many paths that wind and wind, While just the art of being kind Is all the sad world needs. I am the voice of the voiceless; Through me the dumb shall speak, Till the deaf world’s ear be made to hear The wrongs of the wordless weak. From street, from cage, and from kennel, From stable and zoo, the wail Of my tortured kin proclaims the sin Of the mighty against the frail.

Sheldon Allan Shel Silverstein (September 25, 1930 – May 10, 1999), was an American poet, singer-songwriter, cartoonist, screenwriter, and author of children's books. He styled himself as Uncle Shelby in some works. Translated into more than 30 languages, his books have sold over 20 million copies.

Sylvia Plath (October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) was an American poet, novelist and short story writer. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, she studied at Smith College and Newnham College, Cambridge before receiving acclaim as a professional poet and writer. She married fellow poet Ted Hughes in 1956 and they lived together first in the United States and then England, having two children together: Frieda and Nicholas. Following a long struggle with depression and a marital separation, Plath committed suicide in 1963. Controversy continues to surround the events of her life and death, as well as her writing and legacy. Plath is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry and is best known for her two published collections: The Colossus and Other Poems and Ariel. In 1982, she became the first poet to win a Pulitzer Prize posthumously, for The Collected Poems. She also wrote The Bell Jar, a semi-autobiographical novel published shortly before her death.

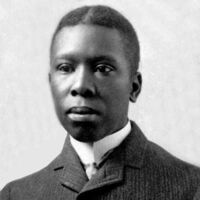

Paul Laurence Dunbar was the first African-American poet to garner national critical acclaim. Born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1872, Dunbar penned a large body of dialect poems, standard English poems, essays, novels and short stories before he died at the age of 33. His work often addressed the difficulties encountered by members of his race and the efforts of African-Americans to achieve equality in America. He was praised both by the prominent literary critics of his time and his literary contemporaries. Dunbar was born on June 27, 1872, to Matilda and Joshua Dunbar, both natives of Kentucky. His mother was a former slave and his father had escaped from slavery and served in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and the 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry Regiment during the Civil War. Matilda and Joshua had two children before separating in 1874. Matilda also had two children from a previous marriage. The family was poor, and after Joshua left, Matilda supported her children by working in Dayton as a washerwoman. One of the families she worked for was the family of Orville and Wilbur Wright, with whom her son attended Dayton's Central High School. Though the Dunbar family had little material wealth, Matilda, always a great support to Dunbar as his literary stature grew, taught her children a love of songs and storytelling. Having heard poems read by the family she worked for when she was a slave, Matilda loved poetry and encouraged her children to read. Dunbar was inspired by his mother, and he began reciting and writing poetry as early as age 6. Dunbar was the only African-American in his class at Dayton Central High, and while he often had difficulty finding employment because of his race, he rose to great heights in school. He was a member of the debating society, editor of the school paper and president of the school's literary society. He also wrote for Dayton community newspapers. He worked as an elevator operator in Dayton's Callahan Building until he established himself locally and nationally as a writer. He published an African-American newsletter in Dayton, the Dayton Tattler, with help from the Wright brothers. His first public reading was on his birthday in 1892. A former teacher arranged for him to give the welcoming address to the Western Association of Writers when the organization met in Dayton. James Newton Matthews became a friend of Dunbar's and wrote to an Illinois paper praising Dunbar's work. The letter was reprinted in several papers across the country, and the accolade drew regional attention to Dunbar; James Whitcomb Riley, a poet whose works were written almost entirely in dialect, read Matthew's letter and acquainted himself with Dunbar's work. With literary figures beginning to take notice, Dunbar decided to publish a book of poems. Oak and Ivy, his first collection, was published in 1892. Though his book was received well locally, Dunbar still had to work as an elevator operator to help pay off his debt to his publisher. He sold his book for a dollar to people who rode the elevator. As more people came in contact with his work, however, his reputation spread. In 1893, he was invited to recite at the World's Fair, where he met Frederick Douglass, the renowned abolitionist who rose from slavery to political and literary prominence in America. Douglass called Dunbar "the most promising young colored man in America." Dunbar moved to Toledo, Ohio, in 1895, with help from attorney Charles A. Thatcher and psychiatrist Henry A. Tobey. Both were fans of Dunbar's work, and they arranged for him to recite his poems at local libraries and literary gatherings. Tobey and Thatcher also funded the publication of Dunbar's second book, Majors and Minors. It was Dunbar's second book that propelled him to national fame. William Dean Howells, a novelist and widely respected literary critic who edited Harper's Weekly, praised Dunbar's book in one of his weekly columns and launched Dunbar's name into the most respected literary circles across the country. A New York publishing firm, Dodd Mead and Co., combined Dunbar's first two books and published them as Lyrics of a Lowly Life. The book included an introduction written by Howells. In 1897, Dunbar traveled to England to recite his works on the London literary circuit. His national fame had spilled across the Atlantic. After returning from England, Dunbar married Alice Ruth Moore, a young writer, teacher and proponent of racial and gender equality who had a master's degree from Cornell University. Dunbar took a job at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. He found the work tiresome, however, and it is believed the library's dust contributed to his worsening case of tuberculosis. He worked there for only a year before quitting to write and recite full time. In 1902, Dunbar and his wife separated. Depression stemming from the end of his marriage and declining health drove him to a dependence on alcohol, which further damaged his health. He continued to write, however. He ultimately produced 12 books of poetry, four books of short stories, a play and five novels. His work appeared in Harper's Weekly, the Sunday Evening Post, the Denver Post, Current Literature and a number of other magazines and journals. He traveled to Colorado and visited his half-brother in Chicago before returning to his mother in Dayton in 1904. He died there on Feb. 9, 1906. Literary style Dunbar's work is known for its colorful language and a conversational tone, with a brilliant rhetorical structure. These traits were well matched to the tune-writing ability of Carrie Jacobs-Bond (1862–1946), with whom he collaborated. Use of dialect Much of Dunbar's work was authored in conventional English, while some was rendered in African-American dialect. Dunbar remained always suspicious that there was something demeaning about the marketability of dialect poems. One interviewer reported that Dunbar told him, "I am tired, so tired of dialect", though he is also quoted as saying, "my natural speech is dialect" and "my love is for the Negro pieces". Though he credited William Dean Howells with promoting his early success, Dunbar was dismayed by his demand that he focus on dialect poetry. Angered that editors refused to print his more traditional poems, he accused Howells of "[doing] my irrevocable harm in the dictum he laid down regarding my dialect verse." Dunbar, however, was continuing a literary tradition that used Negro dialect; his predecessors included Mark Twain, Joel Chandler Harris, and George Washington Cable. Two brief examples of Dunbar's work, the first in standard English and the second in dialect, demonstrate the diversity of the poet's production: (From "Dreams") What dreams we have and how they fly Like rosy clouds across the sky; Of wealth, of fame, of sure success, Of love that comes to cheer and bless; And how they wither, how they fade, The waning wealth, the jilting jade — The fame that for a moment gleams, Then flies forever, — dreams, ah — dreams! (From "A Warm Day In Winter") "Sunshine on de medders, Greenness on de way; Dat's de blessed reason I sing all de day." Look hyeah! What you axing'? What meks me so merry? 'Spect to see me sighin' W'en hit's wa'm in Febawary? List of works * Oak and Ivy (1892) * Majors and Minors (1896) * Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896) * Folks from Dixie (1898) * The Strength of Gideon (1900) * In Old Plantation Days (1903) * The Heart of Happy Hollow (1904) * Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (1905) References Paul Laurence Dunbar Website - www.dunbarsite.org/biopld.asp Wikipedia- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Laurence_Dunbar

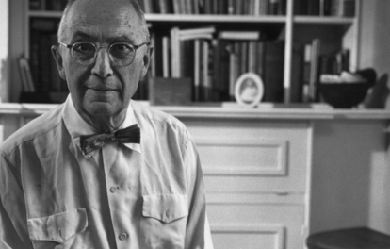

Frederic Ogden Nash (August 19, 1902 – May 19, 1971) was an American poet well known for his light verse. At the time of his death in 1971, The New York Times said his “droll verse with its unconventional rhymes made him the country’s best-known producer of humorous poetry”. Nash wrote over 500 pieces of comic verse. The best of his work was published in 14 volumes between 1931 and 1972.

Carl Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, on January 6, 1878. His parents, August and Clara Johnson, had emigrated to America from the north of Sweden. After encountering several August Johnsons in his job for the railroad, the Sandburg's father renamed the family. The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. While serving, Sandburg met a student at Lombard College, the small school located in Sandburg's hometown. The young man convinced Sandburg to enroll in Lombard after his return from the war.

Anne Sexton (November 9, 1928, Newton, Massachusetts – October 4, 1974, Weston, Massachusetts) was an American poetese, known for her highly personal, confessional verse. She won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1967. Themes of her poetry include her suicidal tendencies, long battle against depression and various intimate details from her private life, including her relationships with her husband and children. Sexton suffered from severe mental illness for much of her life, her first manic episode taking place in 1954.

Madison Julius Cawein (March 23, 1865 – December 8, 1914) was a poet from Louisville, Kentucky. He was the fifth child of William and Christiana (Stelsly) Cawein. His father made patent medicines from herbs thus, as a child, Cawein became acquainted with and developed a love for local nature.

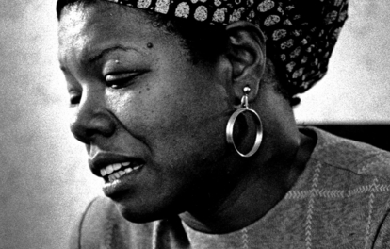

Maya Angelou (born Marguerite Ann Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American author and poet. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry, and is credited with a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning more than fifty years. She received dozens of awards and over thirty honorary doctoral degrees. Angelou is best known for her series of seven autobiographies, which focus on her childhood and early adult experiences. The first, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), tells of her life up to the age of seventeen, and brought her international recognition and acclaim. Angelou's long list of occupations has included pimp, prostitute, night-club dancer and performer, cast-member of the musical Porgy and Bess, coordinator for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, author, journalist in Egypt and Ghana during the days of decolonization, and actor, writer, director, and producer of plays, movies, and public television programs.

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an American expatriate poet, critic and a major figure of the early modernist movement. His contribution to poetry began with his promotion of Imagism, a movement that derived its technique from classical Chinese and Japanese poetry, stressing clarity, precision and economy of language. His best-known works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his unfinished 120-section epic, The Cantos (1917–1969). Working in London in the early 20th century as foreign editor of several American literary magazines, Pound helped to discover and shape the work of contemporaries such as T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Robert Frost, and Ernest Hemingway. He was responsible for the publication in 1915 of Eliot's “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and for the serialization from 1918 of Joyce's Ulysses. Hemingway wrote of him in 1925: “He defends [his friends] when they are attacked, he gets them into magazines and out of jail. ... He writes articles about them. He introduces them to wealthy women. He gets publishers to take their books. He sits up all night with them when they claim to be dying... he advances them hospital expenses and dissuades them from suicide.”

Edward Estlin Cummings (October 14, 1894 – September 3, 1962), popularly known as E. E. Cummings, with the abbreviated form of his name often written by others in lowercase letters as e.e. cummings (in the style of some of his poems—see name and capitalization, below), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. His body of work encompasses approximately 2,900 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as a preeminent voice of 20th century poetry.

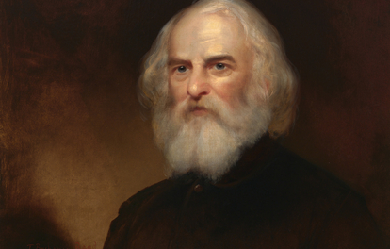

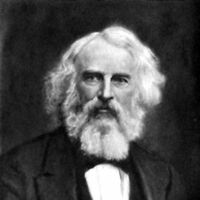

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator whose works include "Paul Revere's Ride", The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline. He was also the first American to translate Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy and was one of the five Fireside Poets. Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, then part of Massachusetts, and studied at Bowdoin College. After spending time in Europe he became a professor at Bowdoin and, later, at Harvard College. His first major poetry collections were Voices of the Night (1839) and Ballads and Other Poems (1841). Longfellow retired from teaching in 1854 to focus on his writing, living the remainder of his life in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a former headquarters of George Washington. His first wife, Mary Potter, died in 1835 after a miscarriage. His second wife, Frances Appleton, died in 1861 after sustaining burns from her dress catching fire. After her death, Longfellow had difficulty writing poetry for a time and focused on his translation. He died in 1882.

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883 – March 4, 1963) was an American poet closely associated with modernism and Imagism. He was also a pediatrician and general practitioner of medicine with a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Williams "worked harder at being a writer than he did at being a physician" but excelled at both. Although his primary occupation was as a family doctor, Williams had a successful literary career as a poet. In addition to poetry (his main literary focus), he occasionally wrote short stories, plays, novels, essays, and translations. He practiced medicine by day and wrote at night. Early in his career, he briefly became involved in the Imagist movement through his friendships with Ezra Pound and H.D. (also known as Hilda Doolittle, another well-known poet whom he befriended while attending the University of Pennsylvania), but soon he began to develop opinions that differed from those of his poet/friends.

James Whitcomb Riley (October 7, 1849 – July 22, 1916) was an American writer, poet, and best-selling author. During his lifetime he was known as the "Hoosier Poet" and "Children's Poet" for his dialect works and his children's poetry respectively. His poems tended to be humorous or sentimental, and of the approximately one thousand poems that Riley authored, the majority are in dialect. His famous works include "Little Orphant Annie" and "The Raggedy Man". Riley began his career writing verses as a sign maker and submitting poetry to newspapers. Thanks in part to an endorsement from poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, he eventually earned successive jobs at Indiana newspaper publishers during the latter 1870s. Riley gradually rose in prominence during the 1880s through his poetry reading tours. He traveled a touring circuit first in the Midwest, and then nationally, holding shows and making joint appearances on stage with other famous talents. Regularly struggling with his alcohol addiction, Riley never married or had children, and created a scandal in 1888 when he became too drunk to perform. He became more popular in spite of the bad press he received, and as a result extricated himself from poorly negotiated contracts that limited his earnings; he quickly became very wealthy. Riley became a bestselling author in the 1890s. His children's poems were compiled into a book and illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy. Titled the Rhymes of Childhood, the book was his most popular and sold millions of copies. As a poet, Riley achieved an uncommon level of fame during his own lifetime. He was honored with annual Riley Day celebrations around the United States and was regularly called on to perform readings at national civic events. He continued to write and hold occasional poetry readings until a stroke paralyzed his right arm in 1910. Riley's chief legacy was his influence in fostering the creation of a midwestern cultural identity and his contributions to the Golden Age of Indiana Literature. Along with other writers of his era, he helped create a caricature of midwesterners and formed a literary community that produced works rivaling the established eastern literati. There are many memorials dedicated to Riley, including the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children. Family and background James Whitcomb Riley was born on October 7, 1849, in the town of Greenfield, Indiana, the third of the six children of Reuben Andrew and Elizabeth Marine Riley.[n 1] Riley's father was an attorney, and in the year before Riley's birth, he was elected a member of the Indiana House of Representatives as a Democrat. He developed a friendship with James Whitcomb, the governor of Indiana, after whom he named his son. Martin Riley, Riley's uncle, was an amateur poet who occasionally wrote verses for local newspapers. Riley was fond of his uncle who helped influence his early interest in poetry. Shortly after Riley's birth, the family moved into a larger house in town. Riley was "a quiet boy, not talkative, who would often go about with one eye shut as he observed and speculated." His mother taught him to read and write at home before sending him to the local community school in 1852. He found school difficult and was frequently in trouble. Often punished, he had nothing kind to say of his teachers in his writings. His poem "The Educator" told of an intelligent but sinister teacher and may have been based on one of his instructors. Riley was most fond of his last teacher, Lee O. Harris. Harris noticed Riley's interest in poetry and reading and encouraged him to pursue it further. Riley's school attendance was sporadic, and he graduated from grade eight at age twenty in 1869. In an 1892 newspaper article, Riley confessed that he knew little of mathematics, geography, or science, and his understanding of proper grammar was poor. Later critics, like Henry Beers, pointed to his poor education as the reason for his success in writing; his prose was written in the language of common people which spurred his popularity. Childhood influences Riley lived in his parents' home until he was twenty-one years old. At five years old he began spending time at the Brandywine Creek just outside Greenfield. His poems "The Barefoot Boy" and "The Old Swimmin' Hole" referred back to his time at the creek. He was introduced in his childhood to many people who later influenced his poetry. His father regularly brought home a variety of clients and disadvantaged people to give them assistance. Riley's poem "The Raggedy Man" was based on a German tramp his father hired to work at the family home. Riley picked up the cadence and character of the dialect of central Indiana from travelers along the old National Road. Their speech greatly influenced the hundreds of poems he wrote in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect. Riley's mother frequently told him stories of fairies, trolls, and giants, and read him children's poems. She was very superstitious, and influenced Riley with many of her beliefs. They both placed "spirit rappings" in their homes on places like tables and bureaus to capture any spirits that may have been wandering about. This influence is recognized in many of his works, including "Flying Islands of the Night." As was common at that time, Riley and his friends had few toys and they amused themselves with activities. With his mother's aid, Riley began creating plays and theatricals which he and his friends would practice and perform in the back of a local grocery store. As he grew older, the boys named their troupe the Adelphians and began to have their shows in barns where they could fit larger audiences. Riley wrote of these early performances in his poem "When We First Played 'Show'," where he referred to himself as "Jamesy." Many of Riley's poems are filled with musical references. Riley had no musical education, and could not read sheet music, but learned from his father how to play guitar, and from a friend how to play violin. He performed in two different local bands, and became so proficient on the violin he was invited to play with a group of adult Freemasons at several events. A few of his later poems were set to music and song, one of the most well known being A Short'nin' Bread Song—Pieced Out. When Riley was ten years old, the first library opened in his hometown. From an early age he developed a love of literature. He and his friends spent time at the library where the librarian read stories and poems to them. Charles Dickens became one Riley's favorites, and helped inspire the poems "St. Lirriper," "Christmas Season," and "God Bless Us Every One." Riley's father enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War, leaving his wife to manage the family home. While he was away, the family took in a twelve-year-old orphan named Mary Alice "Allie" Smith. Smith was the inspiration for Riley's poem "Little Orphant Annie". Riley intended to name the poem "Little Orphant Allie", but a typesetter's error changed the name of the poem during printing. Finding poetry Riley's father returned from the war partially paralyzed. He was unable to continue working in his legal practice and the family soon fell into financial distress. The war had a negative physiological effect on him, and his relationship with his family quickly deteriorated. He opposed Riley's interest in poetry and encouraged him to find a different career. The family finances finally disintegrated and they were forced to sell their town home in April 1870 and return to their country farm. Riley's mother was able to keep peace in the family, but after her death in August from heart disease, Riley and his father had a final break. He blamed his mother's death on his father's failure to care for her in her final weeks. He continued to regret the loss of his childhood home and wrote frequently of how it was so cruelly snatched from him by the war, subsequent poverty, and his mother's death. After the events of 1870, he developed an addiction to alcohol which he struggled with for the remainder of his life. Becoming increasingly belligerent toward his father, Riley moved out of the family home and briefly had a job painting houses before leaving Greenfield in November 1870. He was recruited as a Bible salesman and began working in the nearby town of Rushville, Indiana. The job provided little income and he returned to Greenfield in March 1871 where he started an apprenticeship to a painter. He completed the study and opened a business in Greenfield creating and maintaining signs. His earliest known poems are verses he wrote as clever advertisements for his customers. Riley began participating in local theater productions with the Adelphians to earn extra income, and during the winter months, when the demand for painting declined, Riley began writing poetry which he mailed to his brother living in Indianapolis. His brother acted as his agent and offered the poems to the newspaper Indianapolis Mirror for free. His first poem was featured on March 30, 1872 under the pseudonym "Jay Whit." Riley wrote more than twenty poems to the newspaper, including one that was featured on the front page. In July 1872, after becoming convinced sales would provide more income than sign painting, he joined the McCrillus Company based in Anderson, Indiana. The company sold patent medicines that they marketed in small traveling shows around Indiana. Riley joined the act as a huckster, calling himself the "Painter Poet". He traveled with the act, composing poetry and performing at the shows. After his act he sold tonics to his audience, sometimes employing dishonesty. During one stop, Riley presented himself as a formerly blind painter who had been cured by a tonic, using himself as evidence to encourage the audience to purchase his product. Riley began sending poems to his brother again in February 1873. About the same time he and several friends began an advertisement company. The men traveled around Indiana creating large billboard-like signs on the sides of buildings and barns and in high places that would be visible from a distance. The company was financially successful, but Riley was continually drawn to poetry. In October he traveled to South Bend where he took a job at Stockford & Blowney painting verses on signs for a month; the short duration of his job may have been due to his frequent drunkenness at that time. In early 1874, Riley returned to Greenfield to become a writer full-time. In February he submitted a poem entitled "At Last" to the Danbury News, a Connecticut newspaper. The editors accepted his poem, paid him for it, and wrote him a letter encouraging him to submit more. Riley found the note and his first payment inspiring. He began submitting poems regularly to the editors, but after the newspaper shut down in 1875, Riley was left without a paying publisher. He began traveling and performing with the Adelphians around central Indiana to earn an income while he searched for a new publisher. In August 1875 he joined another traveling tonic show run by the Wizard Oil Company. Newspaper work Riley began sending correspondence to the famous American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow during late 1875 seeking his endorsement to help him start a career as a poet. He submitted many poems to Longfellow, whom he considered to be the greatest living poet. Not receiving a prompt response, he sent similar letters to John Townsend Trowbridge, and several other prominent writers askng for an endorsement. Longfellow finally replied in a brief letter, telling Riley that "I have read [the poems] in great pleasure, and think they show a true poetic faculty and insight." Riley carried the letter with him everywhere and, hoping to receive a job offer and to create a market for his poetry, he began sending poems to dozens of newspapers touting Longfellow's endorsement. Among the newspapers to take an interest in the poems was the Indianapolis Journal, a major Republican Party metropolitan newspaper in Indiana. Among the first poems the newspaper purchased from Riley were "Song of the New Year", "An Empty Nest", and a short story entitled "A Remarkable Man". The editors of the Anderson Democrat discovered Riley's poems in the Indianapolis Journal and offered him a job as a reporter in February 1877. Riley accepted. He worked as a normal reporter gathering local news, writing articles, and assisting in setting the typecast on the printing press. He continued to write poems regularly for the newspaper and to sell other poems to larger newspapers. During the year Riley spent working in Anderson, he met and began to court Edora Mysers. The couple became engaged, but terminated the relationship after they decided against marriage in August. After a rejection of his poems by an eastern periodical, Riley began to formulate a plot to prove his work was of good quality and that it was being rejected only because his name was unknown in the east. Riley authored a poem imitating the style of Edgar Allan Poe and submitted it to the Kokomo Dispatch under a fictitious name claiming it was a long lost Poe poem. The Dispatch published the poem and reported it as such. Riley and two other men who were part of the plot waited two weeks for the poem to be published by major newspapers in Chicago, Boston, and New York to gauge their reaction; they were disappointed. While a few newspapers believed the poem to be authentic, the majority did not, claiming the quality was too poor to be authored by Poe. An employee of the Dispatch learned the truth of the incident and reported it to the Kokomo Tribune, which published an expose that outed Riley as a conspirator behind the hoax. The revelation damaged the credibility of the Dispatch and harmed Riley's reputation. In the aftermath of the Poe plot, Riley was dismissed from the Democrat, so he returned to Greenfield to spend time writing poetry. Back home, he met Clara Louise Bottsford, a school teacher boarding in his father's home. They found they had much in common, particularly their love of literature. The couple began a twelve-year intermittent relationship which would be Riley's longest lasting. In mid-1878 the couple had their first breakup, caused partly by Riley's alcohol addiction. The event led Riley to make his first attempt to give up liquor. He joined a local temperance organization, but quit after a few weeks. Performing poet Without a steady income, his financial situation began to deteriorate. He began submitting his poems to more prominent literary magazines, including Scribner's Monthly, but was informed that although he showed promise, his work was still short of the standards required for use in their publications. Locally, he was still dealing with the stigma of the Poe plot. The Indianapolis Journal and other newspapers refused to accept his poetry, leaving Riley desperate for income. In January 1878 on the advice of a friend, Riley paid an entrance fee to join a traveling lecture circuit where he could give poetry readings. In exchange, he received a portion of the profit his performances earned. Such circuits were popular at the time, and Riley quickly earned a local reputation for his entertaining readings. In August 1878, Riley followed Indiana Governor James D. Williams as speaker at a civic event in a small town near Indianapolis. He recited a recently composed poem, "A Childhood Home of Long Ago," telling of life in pioneer Indiana. The poem was well received and was given good reviews by several newspapers. "Flying Islands of the Night" is the only play that Riley wrote and published. Authored while Riley was traveling with the Adelphians, but never performed, the play has similarities to A Midsummer Night's Dream, which Riley may have used as a model. Flying Islands concerns a kingdom besieged by evil forces of a sinister queen who is defeated eventually by an angel-like heroine. Most reviews were positive. Riley published the play and it became popular in the central Indiana area during late 1878, helping Riley to convince newspapers to again accept his poetry. In November 1879 he was offered a position as a columnist at the Indianapolis Journal and accepted after being encouraged by E.B. Matindale, the paper's chief editor. Although the play and his newspaper work helped expose him to a wider audience, the chief source of his increasing popularity was his performances on the lecture circuit. He made both dramatic and comedic readings of his poetry, and by early 1879 could guarantee large crowds whenever he performed. In an 1894 article, Hamlin Garland wrote that Riley's celebrity resulted from his reading talent, saying "his vibrant individual voice, his flexible lips, his droll glance, united to make him at once poet and comedian—comedian in the sense in which makes for tears as well as for laughter." Although he was a good performer, his acts were not entirely original in style; he frequently copied practices developed by Samuel Clemens and Will Carleton. His tour in 1880 took him to every city in Indiana where he was introduced by local dignitaries and other popular figures, including Maurice Thompson with whom he began to develop a close friendship. Developing and maintaining his publicity became a constant job, and received more of his attention as his fame grew. Keeping his alcohol addiction secret, maintaining the persona of a simple rural poet and a friendly common person became most important. Riley identified these traits as the basis of his popularity during the mid-1880s, and wrote of his need to maintain a fictional persona. He encouraged the stereotype by authoring poetry he thought would help build his identity. He was aided by editorials he authored and submitted to the Indianapolis Journal offering observations on events from his perspective as a "humble rural poet". He changed his appearance to look more mainstream, and began by shaving his mustache off and abandoning the flamboyant dress he employed in his early circuit tours. By 1880 his poems were beginning to be published nationally and were receiving positive reviews. "Tom Johnson's Quit" was carried by newspapers in twenty states, thanks in part to the careful cultivation of his popularity. Riley became frustrated that despite his growing acclaim, he found it difficult to achieve financial success. In the early 1880s, in addition to his steady performing, Riley began producing many poems to increase his income. Half of his poems were written during the period. The constant labor had adverse effects on his health, which was worsened by his drinking. At the urging of Maurice Thompson, he again attempted to stop drinking liquor, but was only able to give it up for a few months. Politics In March 1888, Riley traveled to Washington, D.C. where he had dinner at the White House with other members of the International Copyright League and President of the United States Grover Cleveland. Riley made a brief performance for the dignitaries at the event before speaking about the need for international copyright protections. Cleveland was enamored by Riley's performance and invited him back for a private meeting during which the two men discussed cultural topics. In the 1888 Presidential Election campaign, Riley's acquaintance Benjamin Harrison was nominated as the Republican candidate. Although Riley had shunned politics for most of his life, he gave Harrison a personal endorsement and participated in fund-raising events and vote stumping. The election was exceptionally partisan in Indiana, and Riley found the atmosphere of the campaign stressful; he vowed never to become involved with politics again. Upon Harrison's election, he suggested Riley be named the national poet laureate, but Congress failed to act on the request. Riley was still honored by Harrison and visited him at the White House on several occasions to perform at civic events. Pay problems and scandal Riley and Nye made arrangements with James Pond to make two national tours during 1888 and 1889. The tours were popular and generally sold out, with hundreds having to be turned away. The shows were usually forty-five minutes to an hour long and featured Riley reading often humorous poetry interspersed by stories and jokes from Nye. The shows were informal and the two men adjusted their performances based on their audiences reactions. Riley memorized forty of his poems for the shows to add to his own versatility. Many prominent literary and theatrical people attended the shows. At a New York City show in March 1888, Augustin Daly was so enthralled by the show he insisted on hosting the two men at a banquet with several leading Broadway theatre actors. Despite Riley serving as the act's main draw, he was not permitted to become an equal partner in the venture. Nye and Pond both received a percentage of the net profit, while Riley was paid a flat rate for each performance. In addition, because of Riley's past agreements with the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, he was required to pay half of his fee to his agent Amos Walker. This caused the other men to profit more than Riley from his own work. To remedy this situation, Riley hired his brother-in-law Henry Eitel, an Indianapolis banker, to manage his finances and act on his behalf to try and extricate him from his contract. Despite discussions and assurances from Pond that he would work to address the problem, Eitel had no success. Pond ultimately made the situation worse by booking months of solid performances, not allowing Riley and Nye a day of rest. These events affected Riley physically and emotionally; he became despondent and began his worst period of alcoholism. During November 1889, the tour was forced to cancel several shows after Riley became severely inebriated at a stop in Madison, Wisconsin. Walker began monitoring Riley and denying him access to liquor, but Riley found ways to evade Walker. At a stop at the Masonic Temple Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky, in January 1890, Riley paid the hotel's bartender to sneak whiskey to his room. He became too drunk to perform, and was unable to travel to the next stop. Nye terminated the partnership and tour in response. The reason for the breakup could not be kept secret, and hotel staff reported to the Louisville Courier-Journal that they saw Riley in a drunken stupor walking around the hotel. The story made national news and Riley feared his career was ruined. He secretly left Louisville at night and returned to Indianapolis by train. Eitel defended Riley to the press in an effort to gain sympathy for Riley, explaining the abusive financial arrangements his partners had made. Riley however refused to speak to reporters and hid himself for weeks. Much to Riley's surprise, the news reports made him more popular than ever. Many people thought the stories were exaggerated, and Riley's carefully cultivated image made it difficult for the public to believe he was an alcoholic. Riley had stopped sending poetry to newspapers and magazines in the aftermath, but they soon began corresponding with him requesting that he resume writing. This encouraged Riley, and he made another attempt to give up liquor as he returned to his public career. The negative press did not end however, as Nye and Pond threatened to sue Riley for causing their tour to end prematurely. They claimed to have lost $20,000. Walker threatened a separate suit demanding $1,000. Riley hired Indianapolis lawyer William P. Fishback to represent him and the men settled out of court. The full details of the settlement were never disclosed, but whatever the case, Riley finally extricated himself from his old contracts and became a free agent. The exorbitant amount Riley was being sued for only reinforced public opinion that Riley had been mistreated by his partners, and helped him maintain his image. Nye and Riley remained good friends, and Riley later wrote that Pond and Walker were the source of the problems. Riley's poetry had become popular in Britain, in large part due to his book Old-Fashioned Roses. In May 1891 he traveled to England to make a tour and what he considered a literary pilgrimage. He landed in Liverpool and traveled first to Dumfries, Scotland, the home and burial place of Robert Burns. Riley had long been compared to Burns by critics because they both used dialect in their poetry and drew inspiration from their rural homes. He then traveled to Edinburgh, York, and London, reciting poetry for gatherings at each stop. Augustin Daly arranged for him to give a poetry reading to prominent British actors in London. Riley was warmly welcomed by its literary and theatrical community and he toured places that Shakespeare had frequented. Riley quickly tired of traveling abroad and began longing for home, writing to his nephew that he regretted having left the United States. He curtailed his journey and returned to New York City in August. He spent the next months in his Greenfield home attempting to write an epic poem, but after several attempts gave up, believing he did not possess the ability. By 1890, Riley had authored almost all of his famous poems. The few poems he did write during the 1890s were generally less well received by the public. As a solution, Riley and his publishers began reusing poetry from other books and printing some of his earliest works. When Neighborly Poems was published in 1891, a critic working for the Chicago Tribune pointed out the use of Riley's earliest works, commenting that Riley was using his popularity to push his crude earlier works onto the public only to make money. Riley's newest poems published in the 1894 book Armazindy received very negative reviews that referred to poems like "The Little Dog-Woggy" and "Jargon-Jingle" as "drivel" and to Riley as a "worn out genius." Most of his growing number of critics suggested that he ignored the quality of the poems for the sake of making money. National poet Riley had become very wealthy by the time he ended touring in 1895, and was earning $1,000 a week. Although he retired, he continued to make minor appearances. In 1896, Riley performed four shows in Denver. Most of the performances of his later life were at civic celebrations. He was a regular speaker at Decoration Day events and delivered poetry before the unveiling of monuments in Washington, D.C. Newspapers began referring to him as the "National Poet", "the poet laureate of America", and "the people's poet laureate". Riley wrote many of his patriotic poems for such events, including "The Soldier", "The Name of Old Glory", and his most famous such poem, "America!". The 1902 poem "America, Messiah of Nations" was written and read by Riley for the dedication of the Indianapolis Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. The only new poetry Riley published after the end of the century were elegies for famous friends. The poetic qualities of the poems were often poor, but they contained many popular sentiments concerning the deceased. Among those he eulogized were Benjamin Harrison, Lew Wallace, and Henry Lawton. Because of the poor quality of the poems, his friends and publishers requested that he stop writing them, but he refused. In 1897, Riley's publishers suggested that he create a multi-volume series of books containing his complete life works. With the help of his nephew, Riley began working to compile the books, which eventually totaled sixteen volumes and were finally completed in 1914. Such works were uncommon during the lives of writers, attesting to the uncommon popularity Riley had achieved. His works had become staples for Ivy League literature courses and universities began offering him honorary degrees. The first was Yale in 1902, followed by a Doctorate of Letters from the University of Pennsylvania in 1904. Wabash College and Indiana University granted him similar awards. In 1908 he was elected member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and in 1912 they conferred upon him a special medal for poetry. Riley was influential in helping other poets start their careers, having particularly strong influences on Hamlin Garland, William Allen White, and Edgar Lee Masters. He discovered aspiring African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1892. Riley thought Dunbar's work was "worthy of applause", and wrote him letters of recommendation to help him get his work published. Declining health In 1901, Riley's doctor diagnosed him with neurasthenia, a nervous disorder, and recommended long periods of rest as a cure.[173] Riley remained ill for the rest of his life and relied on his landlords and family to aid in his care. During the winter months he moved to Miami, Florida, and during summer spent time with his family in Greenfield. He made only a few trips during the decade, including one to Mexico in 1906. He became very depressed by his condition, writing to his friends that he thought he could die at any moment, and often used alcohol for relief.[174] In March 1909, Riley was stricken a second time with Bell's palsy, and partial deafness, the symptoms only gradually eased over the course of the year.[175] Riley was a difficult patient, and generally refused to take any medicine except the patent medicines he had sold in his earlier years; the medicines often worsened his conditions, but his doctors could not sway his opinion.[176] On July 10, 1910 he suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. Hoping for a quick recovery, his family kept the news from the press until September. Riley found the loss of use of his writing hand the worst part of the stroke, which served only to further depress him.[174][177] With his health so poor, he decided to work on a legacy by which to be remembered in Indianapolis. In 1911 he donated land and funds to build a new library on Pennsylvania Avenue.[178] By 1913, with the aid of a cane, Riley began to recover his ability to walk. His inability to write, however, nearly ended his production of poems. George Ade worked with him from 1910 through 1916 to write his last five poems and several short autobiographical sketches as Riley dictated. His publisher continued recycling old works into new books, which remained in high demand.[178] Since the mid-1880s, Riley had been the nation's most read poet, a trend that accelerated at the turn of the century. In 1912 Riley recorded readings of his most popular poetry to be sold by Victor Records. Riley was the subject of three paintings by T. C. Steele. The Indianapolis Arts Association commissioned a portrait of Riley to be created by world famous painter John Singer Sargent. Riley's image became a nationally known icon and many businesses capitalized on his popularity to sell their products; Hoosier Poet brand vegetables became a major trade-name in the midwest.[179] In 1912, the governor of Indiana instituted Riley Day on the poet's birthday. Schools were required to teach Riley's poems to their children, and banquet events were held in his honor around the state. In 1915 and 1916 the celebration was national after being proclaimed in most states. The annual celebration continued in Indiana until 1968.[180] In early 1916 Riley was filmed as part of a movie to celebrate Indiana's centennial, the video is on display at the Indiana State Library.[181][182] Death and legacy On July 22, 1916, Riley suffered a second stroke. He recovered enough during the day to speak and joke with his companions. He died before dawn the next morning, July 23.[183] Riley's death shocked the nation and made front page headlines in major newspapers.[184] President Woodrow Wilson wrote a brief note to Riley's family offering condolences on behalf the entire nation. Indiana Governor Samuel M. Ralston offered to allow Riley to lie in state at the Indiana Statehouse—Abraham Lincoln being the only other person to have previously received such an honor.[185] During the ten hours he lay in state on July 24, more than thirty-five thousand people filed past his bronze casket; the line was still miles long at the end of the day and thousands were turned away. The next day a private funeral ceremony was held and attended by many dignitaries. A large funeral procession then carried him to Crown Hill Cemetery where he was buried in a tomb at the top of the hill, the highest point in the city of Indianapolis.[186] Within a year of Riley's death many memorials were created, including several by the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association. The James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children was created and named in his honor by a group of wealthy benefactors and opened in 1924. In the following years, other memorials intended to benefit children were created, including Camp Riley for youth with disabilities.[187][188] The memorial foundation purchased the poet's Lockerbie home in Indianapolis and it is now maintained as a museum. The James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home is the only late-Victorian home in Indiana that is open to the public and the United States' only late-Victorian preservation, featuring authentic furniture and decor from that era. His birthplace and boyhood home, now the James Whitcomb Riley House, is preserved as a historical site.[189] A Liberty ship, commissioned April 23, 1942, was christened the SS James Whitcomb Riley. It served with the United States Maritime Commission until being scrapped in 1971. James Whitcomb Riley High School opened in South Bend, Indiana in 1924. In 1950, there was a James Whitcomb Riley Elementary School in Hammond, Indiana, but it was torn down in 2006. East Chicago, Indiana had a Riley School at one time, as did neighboring Gary, Indiana and Anderson, Indiana. One of New Castle, Indiana's elementary schools is named for Riley as is the road on which it is located. The former Greenfield High School was converted to Riley Elementary School and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. In 1940, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 10-cent stamp honoring Riley.[190] As a lasting tribute, the citizens of Greenfield hold a festival every year in Riley's honor. Taking place the first or second weekend of October, the "Riley Days" festival traditionally commences with a flower parade in which local school children place flowers around Myra Reynolds Richards' statue of Riley on the county courthouse lawn, while a band plays lively music in honor of the poet. Weeks before the festival, the festival board has a queen contest. The 2010–2011 queen was Corinne Butler. The pageant has been going on many years in honor of the Hoosier poet[191] According to historian Elizabeth Van Allen, Riley was instrumental in helping form a midwestern cultural identity. The midwestern United States had no significant literary community before the 1880s.[192] The works of the Western Association of Writers, most notably those of Riley and Wallace, helped create the midwest's cultural identity and create a rival literary community to the established eastern literari. For this reason, and the publicity Riley's work created, he was commonly known as the "Hoosier Poet." Critical reception and style Riley was among the most popular writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, known for his "uncomplicated, sentimental, and humorous" writing.[195] Often writing his verses in dialect, his poetry caused readers to recall a nostalgic and simpler time in earlier American history. This gave his poetry a unique appeal during a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization in the United States. Riley was a prolific writer who "achieved mass appeal partly due to his canny sense of marketing and publicity."[195] He published more than fifty books, mostly of poetry and humorous short stories, and sold millions of copies.[195] Riley is often remembered for his most famous poems, including the "The Raggedy Man" and "Little Orphant Annie". Many of his poems, including those, where partially autobiographical, as he used events and people from his childhood as an inspiration for subject matter.[195] His poems often contained morals and warnings for children, containing messages telling children to care for the less fortunate of society. David Galens and Van Allen both see these messages as Riley's subtle response to the turbulent economic times of the Gilded Age and the growing progressive movement.[196] Riley believed that urbanization robbed children of their innocence and sincerity, and in his poems he attempted to introduce and idolize characters who had not lost those qualities.[197] His children's poems are "exuberant, performative, and often display Riley's penchant for using humorous characterization, repetition, and dialect to make his poetry accessible to a wide-ranging audience."[195][198] Although hinted at indirectly in some poems, Riley wrote very little on serious subject matter, and actually mocked attempts at serious poetry. Only a few of his sentimental poems concerned serious subjects. "Little Mandy's Christmas-Tree", "The Absence of Little Wesley", and "The Happy Little Cripple" were about poverty, the death of a child, and disabilities. Like his children's poems, they too contained morals, suggesting society should pity the downtrodden and be charitable.[195][198] Riley wrote gentle and romantic poems that were not in dialect. They generally consisted of sonnets and were strongly influenced by the works of John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. His standard English poetry was never as popular as his Hoosier dialect poems.[195] Still less popular were the poems Riley authored in his later years; most were to commemorate important events of American history and to eulogize the dead.[195] Riley's contemporaries acclaimed him "America's best-loved poet".[195][198] In 1920, Henry Beers lauded the works of Riley "as natural and unaffected, with none of the discontent and deep thought of cultured song."[195] Samuel Clemens, William Dean Howells, and Hamlin Garland, each praised Riley's work and the idealism he expressed in his poetry. Only a few critics of the period found fault with Riley's works. Ambrose Bierce criticized Riley for his frequent use of dialect. Bierce accused Riley of using dialect to "cover up [the] faulty construction" of his poems.[195] Edgar Lee Masters found Riley's work to be superficial, claiming it lacked irony and that he had only a "narrow emotional range".[195] By the 1930s popular critical opinion towards Riley's works began to shift in favor of the negative reviews. In 1951, James T. Farrell said Riley's works were "cliched." Galens wrote that modern critics consider Riley to be a "minor poet, whose work—provincial, sentimental, and superficial though it may have been—nevertheless struck a chord with a mass audience in a time of enormous cultural change."[195] Thomas C. Johnson wrote that what most interests modern critics was Riley's ability to market his work, saying he had a unique understanding of "how to commodify his own image and the nostalgic dreams of an anxious nation."[195] Among the earliest widespread criticisms of Riley were opinions that his dialect writing did not actually represent the true dialect of central Indiana. In 1970 Peter Revell wrote that Riley's dialect was more similar to the poor speech of a child rather than the dialect of his region. Revell made extensive comparison to historical texts and Riley's dialect usage. Philip Greasley wrote that that while "some critics have dismissed him as sub-literary, insincere, and an artificial entertainer, his defenders reply that an author so popular with millions of people in different walks of life must contribute something of value, and that his faults, if any, can be ignored." References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Whitcomb_Riley

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that “the negro was in vogue” which was later paraphrased as “when Harlem was in vogue”.

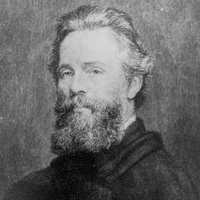

Herman Melville (August 1, 1819– September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period best known for Typee (1846), a romantic account of his experiences in Polynesian life, and his whaling novel Moby-Dick (1851). His work was almost forgotten during his last thirty years. His writing draws on his experience at sea as a common sailor, exploration of literature and philosophy, and engagement in the contradictions of American society in a period of rapid change. He developed a complex, baroque style: the vocabulary is rich and original, a strong sense of rhythm infuses the elaborate sentences, the imagery is often mystical or ironic, and the abundance of allusion extends to Scripture, myth, philosophy, literature, and the visual arts.