Alda Giuseppina Angela Merini (Milano, 21 marzo 1931 – Milano, 1º novembre 2009) è stata una poetessa, aforista e scrittrice italiana. «Ho la sensazione di durare troppo, di non riuscire a spegnermi: come tutti i vecchi le mie radici stentano a mollare la terra. Ma del resto dico spesso a tutti che quella croce senza giustizia che è stato il mio manicomio non ha fatto che rivelarmi la grande potenza della vita.»

Arturo Borja Pérez, (n. Quito, 1892 - f. Ibídem, 13 de noviembre de 1912) fue un poeta ecuatoriano, perteneciente al movimiento llamado “La Generación Decapitada” y el primero del grupo en despuntar como modernista. Es muy escasa su obra artística pero suficiente para determinar la calidad de poeta: una corona de veinte composiciones forma el libro titulado La flauta de ónix, y seis poemas más; obras que fueron publicadas póstumamente. Se suicidó en la ciudad de Quito, el 13 de noviembre de 1912, contando apenas con 20 años de edad. Ofrenda de rosas (A Arturo Borja) Recuerdo que te hallé por mi camino como un Verlaine aún adolescente, ¡y daba el signo de un fatal destino tu alma de estirpe lírica y ardiente! Y ambos fraternizamos; que tus rosas para todas las almas entreabrías, ¡haciéndote en las horas humildosas dueño de todas las melancolías...! Quién volviera a tus ojos, en ofrenda, la vida humilde que suspira y canta, como el Rubí de manos de leyenda que antaño dijo a Lázaro: ¡Levanta! Evoco el sueño juvenil de un día que, en el Claustro del Arte bien sentido, matamos la viril hipocrecía, y laboramos lentos el gemido. Y ahora la luna de tu sistro agrestre, al visitar nuestro santurario frío, da su color de lágrima celeste en el cristal de tu crisol vacío... ¡Adiós, fuente de lánguido quebranto!, que volvías un Fénix mi rosal, ¡encantando las rosas sin encanto cuando el encanto huía con el mal! ¡Adiós, fuente de lágrimas cantoras que halagaron el viaje juvenil!; de la angustia de Abril refrescadoras como lluvias caídas en Abril... Duerme y reposa; que quizás es bueno sólo el sueño sin sueño en que caíste, ¡la flor de espino y el laurel de heleno entremezclados en tu frente triste! —Humberto Fierro Feliz tú, hermano mío (Al espíritu fraternal de Arturo Borja) Poeta, hermano mío, que como yo sufriste, el frío del vacío y la grandeza triste de saberte una nube en prisión de rocío; tu buen hermano en lira, en rosa, azul y luna que inspira la mentira de la verde laguna, sabe envidiar tu suerte porque tu suerte admira. Lloro tu vida breve por lo que dado hubieras, pero la leve nieve de tus quimeras en nube se transforma y desde lo alto llueve. Poeta, hermano mío, ya no estarás más triste, ni el frío del vacío sentirás que sentiste... Ya no eres una nube encerrada en rocío; después de que partiste tu lluvia se hizo un río que da savia a tu rosa y a tu bulbul alpiste... ¡Feliz tú, hermano mío! —Alejandro Sux

Thomas Stearns Eliot OM (26 September 1888– 4 January 1965) was a British essayist, publisher, playwright, literary and social critic, and “one of the twentieth century’s major poets”. He moved from his native United States to England in 1914 at the age of 25, settling, working, and marrying there. He was eventually naturalised as a British subject in 1927 at the age of 39, renouncing his American citizenship. Eliot attracted widespread attention for his poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (1915), which was seen as a masterpiece of the Modernist movement. It was followed by some of the best-known poems in the English language, including The Waste Land (1922), “The Hollow Men” (1925), “Ash Wednesday” (1930), and Four Quartets (1943). He was also known for his seven plays, particularly Murder in the Cathedral (1935). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948, “for his outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry”.

.jpeg?locale=it)

Thomas Moore (28 May 1779 – 25 February 1852), also known as Tom Moore, was an Irish writer, poet, and lyricist celebrated for his Irish Melodies. His setting of English-language verse to old Irish tunes marked the transition in popular Irish culture from Irish to English. Politically, Moore was recognised in England as a press, or "squib", writer for the aristocratic Whigs; in Ireland he was accounted a Catholic patriot.

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (November 10, 1879– December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern singing poetry, as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted. Crushed by financial worry and in failing health from his six-month road trip, Lindsay sank into depression. While in New York in 1905 Lindsay turned to poetry in earnest. He tried to sell his poems on the streets. Self-printing his poems, he began to barter a pamphlet titled “Rhymes To Be Traded For Bread”, which he traded for food as a self-perceived modern version of a medieval troubadour. On December 5, 1931, he committed suicide by drinking a bottle of Lysol. His last words were: “They tried to get me; I got them first!”

Sara Teasdale (August 8, 1884 – January 29, 1933) was an American lyric poet. She was born Sarah Trevor Teasdale in St. Louis, Missouri, and used the name Sara Teasdale Filsinger after her marriage in 1914. She had such poor health for so much of her childhood, home schooled until age 9, that it was only at age 10 that she was well enough to begin school. She started at Mary Institute in 1898, but switched to Hosmer Hall in 1899, graduating in 1903. I Shall Not Care WHEN I am dead and over me bright April Shakes out her rain-drenched hair, Tho' you should lean above me broken-hearted, I shall not care. I shall have peace, as leafy trees are peaceful When rain bends down the bough, And I shall be more silent and cold-hearted Than you are now.

Vicente García-Huidobro Fernández (Santiago, 10 de enero de 1893 – Cartagena, 2 de enero de 1948), más conocido como Vicente Huidobro, fue un poeta chileno. Iniciador y exponente del creacionismo, es considerado uno de los más destacados poetas chilenos, junto con Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda y Pablo de Rokha. Nació en el seno de una familia adinerada, relacionada con la política y la banca. Su padre era el heredero del marquesado de Casa Real y su madre, una activista feminista y anfitriona de numerosas veladas literarias.

Ramón Modesto López Velarde Berumen (Jerez de García Salinas, Zacatecas, México, 15 de junio de 1888 – Ciudad de México, 19 de junio de 1921) fue un poeta mexicano. Su obra suele encuadrarse en el postmodernismo literario. En México alcanzó una gran fama, llegando a ser considerado el poeta nacional. Nació en Jerez, municipio del estado de Zacatecas, primero de los nueve hijos del abogado José Guadalupe López Velarde y Trinidad Berumen Llamas, de una familia de terratenientes locales.

Dorothy Parker (August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet, short story writer, critic and satirist, best known for her wit, wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles. From a conflicted and unhappy childhood, Parker rose to acclaim, both for her literary output in such venues as The New Yorker and as a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table. Following the breakup of the circle, Parker traveled to Hollywood to pursue screenwriting. Her successes there, including two Academy Award nominations, were curtailed as her involvement in left-wing politics led to a place on the Hollywood blacklist. Dismissive of her own talents, she deplored her reputation as a “wisecracker”. Nevertheless, her literary output and reputation for her sharp wit have endured.

Rafael Pombo, (Bogotá, República de Nueva Granada, 7 de noviembre de 1833 – Bogotá, Colombia, 5 de mayo de 1924), fue un poeta, escritor, fabulista, traductor, intelectual y diplomático colombiano. Sus padres fueron Lino de Pombo O'Donnell y Ana María Rebolledo, ambos pertenecientes a familias de la aristocracia de Popayán. Cuando el General Francisco de Paula Santander designó a Lino de Pombo como secretario del Interior y de Relaciones Exteriores, éste aceptó y viajó desde Popayán con su familia a Bogotá. Cuando la familia llegó a Bogotá, Ana María Rebolledo tenía 9 meses de embarazo, por lo que poco después dio a luz a su primogénito José Rafael de Pombo Rebolledo.

José Emilio Pacheco (Ciudad de México, 30 de junio de 1939 - Ib., 26 de enero de 2014) fue un destacado escritor mexicano principalmente por su poesía, aunque cultivó con éxito también la crónica, la novela, el cuento, el ensayo y la traducción. Se le considera integrante de la llamada generación de los cincuenta o de medio siglo. Comparte la perspectiva cosmopolita que caracteriza a los literatos de esa generación, y los temas que aborda en sus textos van desde la historia y el tiempo cíclico, los universos de la infancia y de lo fantástico, hasta la ciudad y la muerte. La escritura de Pacheco se distingue por un constante cuestionamiento sobre la vida en el mundo moderno, sobre la literatura y su propia producción artística, así como por el uso de un lenguaje sin rebuscamientos, accesible.

Nicanor Segundo Parra Sandoval (San Fabián de Alico, 5 de septiembre de 1914 – La Reina, Santiago, 23 de enero de 2018) fue un poeta, profesor, físico e intelectual chileno cuya obra ha tenido una profunda influencia en la literatura hispanoamericana. Considerado el creador de la antipoesía, es para muchos críticos y autores connotados, tales como Harold Bloom, Niall Binns o Roberto Bolaño, uno de los mejores poetas de Occidente. El mayor de la familia Parra, recibió el Premio Nacional de Literatura (1969) y el Premio Miguel de Cervantes (2011).

Celia Laighton Thaxter (June 29, 1835 – August 25, 1894) was an American writer of poetry and stories. She was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thaxter grew up in the Isles of Shoals, first on White Island, where her father, Thomas Laighton, was a lighthouse keeper, and then on Smuttynose and Appledore Islands. When she was sixteen, she married Levi Thaxter and moved to the mainland, residing first in Watertown, Massachusetts at a property his father owned. Celia died suddenly while on Appledore Island. She was buried not far from her cottage, which unfortunately burned in the 1914 fire that destroyed The Appledore House hotel.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835– April 21, 1910), better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. Among his novels are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), the latter often called “The Great American Novel”.

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the Fireside Poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet Robert Burns. Whittier is remembered particularly for his anti-slavery writings as well as his book Snow-Bound.

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist and journalist. His work is marked by clarity, intelligence and wit, awareness of social injustice, opposition to totalitarianism, and belief in democratic socialism. Considered perhaps the 20th century's best chronicler of English culture, Orwell wrote literary criticism, poetry, fiction and polemical journalism. He is best known for the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and the allegorical novella Animal Farm (1945), which together have sold more copies than any two books by any other 20th-century author. His book Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, is widely acclaimed, as are his numerous essays on politics, literature, language and culture. In 2008, The Times ranked him second on a list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945”.

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s. Today he is remembered for his epigrams, plays and the circumstances of his imprisonment, followed by his early death. At the turn of the 1890s, he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of dialogues and essays, and incorporated themes of decadence, duplicity, and beauty into his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). The opportunity to construct aesthetic details precisely, and combine them with larger social themes, drew Wilde to write drama. He wrote Salome (1891) in French in Paris but it was refused a licence. Unperturbed, Wilde produced four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late Victorian London.

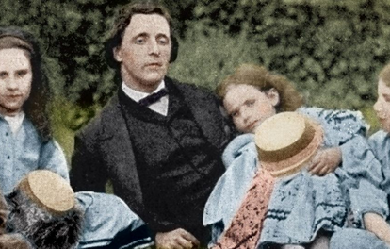

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, was an English author, mathematician, logician, Anglican deacon and photographer. His most famous writings are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, as well as the poems "The Hunting of the Snark" and "Jabberwocky", all examples of the genre of literary nonsense. He is noted for his facility at word play, logic, and fantasy, and there are societies in many parts of the world (including the United Kingdom, Japan, the United States, and New Zealand) dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life. Antecedents Dodgson's family was predominantly northern English, with Irish connections. Conservative and High Church Anglican, most of Dodgson's ancestors were army officers or Church of England clergy. His great-grandfather, also named Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become the Bishop of Elphin. His grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in Ireland in 1803 when his two sons were hardly more than babies. His mother's name was Frances Jane Lutwidge. The elder of these sons – yet another Charles Dodgson – was Carroll's father. He reverted to the other family tradition and took holy orders. He went to Westminster School, and then to Christ Church, Oxford. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead he married his first cousin in 1827 and became a country parson. Dodgson was born in the little parsonage of Daresbury in Cheshire near the towns of Warrington and Runcorn, the eldest boy but already the third child of the four-and-a-half-year-old marriage. Eight more children were to follow. When Charles was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees in North Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious rectory. This remained their home for the next twenty-five years. Young Charles' father was an active and highly conservative cleric of the Church of England who later became the Archdeacon of Richmond and involved himself, sometimes influentially, in the intense religious disputes that were dividing the church. He was High Church, inclining to Anglo-Catholicism, an admirer of John Henry Newman and the Tractarian movement, and did his best to instill such views in his children. Young Charles was to develop an ambiguous relationship with his father's values and with the Church of England as a whole. Education Home life During his early youth, Dodgson was educated at home. His "reading lists" preserved in the family archives testify to a precocious intellect: at the age of seven the child was reading The Pilgrim's Progress. He also suffered from a stammer – a condition shared by most of his siblings – that often influenced his social life throughout his years. At age twelve he was sent to Richmond Grammar School (now part of Richmond School) at nearby Richmond. Rugby In 1846, young Dodgson moved on to Rugby School, where he was evidently less happy, for as he wrote some years after leaving the place: I cannot say ... that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again ... I can honestly say that if I could have been ... secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear. Scholastically, though, he excelled with apparent ease. "I have not had a more promising boy at his age since I came to Rugby", observed R.B. Mayor, then Mathematics master. Oxford He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and matriculated at Oxford in May 1850 as a member of his father's old college, Christ Church. After waiting for rooms in college to become available, he went into residence in January 1851. He had been at Oxford only two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of "inflammation of the brain" – perhaps meningitis or a stroke – at the age of forty-seven. His early academic career veered between high promise and irresistible distraction. He did not always work hard, but was exceptionally gifted and achievement came easily to him. In 1852 he obtained first-class honours in Mathematics Moderations, and was shortly thereafter nominated to a Studentship by his father's old friend, Canon Edward Pusey. In 1854 he obtained first-class honours in the Final Honours School of Mathematics, graduating Bachelor of Arts. He remained at Christ Church studying and teaching, but the next year he failed an important scholarship through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study. Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855, which he continued to hold for the next twenty-six years. Despite early unhappiness, Dodgson was to remain at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death. Character and appearance Health challenges The young adult Charles Dodgson was about six feet tall, slender, and had curling brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat asymmetrical, and as carrying himself rather stiffly and awkwardly, though this may be on account of a knee injury sustained in middle age. As a very young child, he suffered a fever that left him deaf in one ear. At the age of seventeen, he suffered a severe attack of whooping cough, which was probably responsible for his chronically weak chest in later life. Another defect he carried into adulthood was what he referred to as his "hesitation", a stammer he acquired in early childhood and which plagued him throughout his life. The stammer has always been a potent part of the conceptions of Dodgson; it is part of the belief that he stammered only in adult company and was free and fluent with children, but there is no evidence to support this idea. Many children of his acquaintance remembered the stammer while many adults failed to notice it. Dodgson himself seems to have been far more acutely aware of it than most people he met; it is said he caricatured himself as the Dodo in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is one of the many "facts" often-repeated, for which no firsthand evidence remains. He did indeed refer to himself as the dodo, but that this was a reference to his stammer is simply speculation. Although Dodgson's stammer troubled him, it was never so debilitating that it prevented him from applying his other personal qualities to do well in society. At a time when people commonly devised their own amusements and when singing and recitation were required social skills, the young Dodgson was well-equipped to be an engaging entertainer. He reportedly could sing tolerably well and was not afraid to do so before an audience. He was adept at mimicry and storytelling, and was reputedly quite good at charades. Social connections In the interim between his early published writing and the success of the Alice books, Dodgson began to move in the Pre-Raphaelite social circle. He first met John Ruskin in 1857 and became friendly with him. He developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his family, and also knew William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Arthur Hughes, among other artists. He also knew the fairy-tale author George MacDonald well – it was the enthusiastic reception of Alice by the young MacDonald children that convinced him to submit the work for publication. Politics, religion and philosophy In broad terms, Dodgson has traditionally been regarded as politically, religiously, and personally conservative. Martin Gardner labels Dodgson as a Tory who was "awed by lords and inclined to be snobbish towards inferiors." The Revd W. Tuckwell, in his Reminiscences of Oxford (1900), regarded him as "austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice's landscape." However, Dodgson also expressed interest in philosophies and religions that seem at odds with this assessment. For example, he was a founding member of the Society for Psychical Research. It has been argued by the proponents of the 'Carroll Myth' that these factors require a reconsideration of Gardner's diagnosis, and that perhaps, Dodgson's true outlook was more complex than previously believed (see 'the Carroll Myth' below). Dodgson wrote some studies of various philosophical arguments. In 1895, he developed a philosophical regressus-argument on deductive reasoning in his article "What the Tortoise Said to Achilles", which appeared in one of the early volumes of the philosophical journal Mind. The article was reprinted in the same journal a hundred years later, in 1995, with a subsequent article by Simon Blackburn titled Practical Tortoise Raising. Artistic activities Literature From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, both contributing heavily to the family magazine Mischmasch and later sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications, The Comic Times and The Train, as well as smaller magazines like the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic. Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. "I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser), but I do not despair of doing so some day," he wrote in July 1855. Sometime after 1850, he did write puppet plays for his siblings' entertainment, of which one has survived, La Guida di Bragia. In 1856 he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A romantic poem called "Solitude" appeared in The Train under the authorship of "Lewis Carroll." This pseudonym was a play on his real name; Lewis was the anglicised form of Ludovicus, which was the Latin for Lutwidge, and Carroll an Irish surname similar to the Latin name Carolus, from which the name Charles comes. Alice In the same year, 1856, a new Dean, Henry Liddell, arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson's life and, over the following years, greatly influence his writing career. Dodgson became close friends with Liddell's wife, Lorina, and their children, particularly the three sisters: Lorina, Edith and Alice Liddell. He was for many years widely assumed to have derived his own "Alice" from Alice Liddell. This was given some apparent substance by the fact the acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking Glass spells out her name, and that there are many superficial references to her hidden in the text of both books. It has been pointed out that Dodgson himself repeatedly denied in later life that his "little heroine" was based on any real child, and frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text. Gertrude Chataway's name appears in this form at the beginning of The Hunting of the Snark, and no one has ever suggested this means any of the characters in the narrative are based on her. Though information is scarce (Dodgson's diaries for the years 1858–1862 are missing), it does seem clear that his friendship with the Liddell family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) on rowing trips accompanied by an adult friend to nearby Nuneham Courtenay or Godstow. It was on one such expedition, on 4 July 1862, that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and largest commercial success. Having told the story and been begged by Alice Liddell to write it down, Dodgson eventually (after much delay) presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice's Adventures Under Ground in November 1864. Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald read Dodgson's incomplete manuscript, and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles Alice Among the Fairies and Alice's Golden Hour were rejected, the work was finally published as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen-name, which Dodgson had first used some nine years earlier. The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently thought that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson's life in many ways. The fame of his alter ego "Lewis Carroll" soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. Indeed, according to one popular story, Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Alice In Wonderland so much that she suggested he dedicate his next book to her, and was accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly mathematical volume entitled An Elementary Treatise on Determinants. Dodgson himself vehemently denied this story, commenting "...It is utterly false in every particular: nothing even resembling it has occurred"; and it is unlikely for other reasons: as T.B. Strong comments in a Times article, "It would have been clean contrary to all his practice to identify [the] author of Alice with the author of his mathematical works". He also began earning quite substantial sums of money but continued with his seemingly disliked post at Christ Church. Late in 1871, a sequel – Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There – was published. (The title page of the first edition erroneously gives "1872" as the date of publication.) Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects the changes in Dodgson's life. His father had recently died (1868), plunging him into a depression that lasted some years. The Hunting of the Snark In 1876, Dodgson produced his last great work, The Hunting of the Snark, a fantastical "nonsense" poem, exploring the adventures of a bizarre crew of tradesmen, and one beaver, who set off to find the eponymous creature. The painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti reputedly became convinced the poem was about him. Photography In 1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography, first under the influence of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later his Oxford friend Reginald Southey. He soon excelled at the art and became a well-known gentleman-photographer, and he seems even to have toyed with the idea of making a living out of it in his very early years. A recent study by Roger Taylor and Edward Wakeling exhaustively lists every surviving print, and Taylor calculates that just over fifty percent of his surviving work depicts young girls, though this may be a highly distorted figure as approximately 60% of his original photographic portfolio is now missing, so any firm conclusions are difficult. Dodgson also made many studies of men, women, male children and landscapes; his subjects also include skeletons, dolls, dogs, statues and paintings, and trees. His pictures of children were taken with a parent in attendance and many of the pictures were taken in the Liddell garden, because natural sunlight was required for good exposures. He also found photography to be a useful entrée into higher social circles. During the most productive part of his career, he made portraits of notable sitters such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron, Michael Faraday and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Dodgson abruptly ceased photography in 1880. Over 24 years, he had completely mastered the medium, set up his own studio on the roof of Tom Quad, and created around 3, images. Fewer than 1, have survived time and deliberate destruction. He reported that he stopped taking photographs because keeping his studio working was difficult (he used the wet collodion process) and commercial photographers (who started using the dry plate process in the 1870s) took pictures more quickly. With the advent of Modernism, tastes changed, and his photography was forgotten from around 1920 until the 1960s. Inventions To promote letter writing, Dodgson invented The Wonderland Postage-Stamp Case in 1889. This was a cloth-backed folder with twelve slots, two marked for inserting the then most commonly used penny stamp, and one each for the other current denominations to one shilling. The folder was then put into a slip case decorated with a picture of Alice on the front and the Cheshire Cat on the back. All could be conveniently carried in a pocket or purse. When issued it also included a copy of Carroll's pamphletted lecture, Eight or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing. Reconstructed nyctograph, with scale demonstrated by a 5 euro cent. Another invention is a writing tablet called the nyctograph for use at night that allowed for note-taking in the dark; thus eliminating the trouble of getting out of bed and striking a light when one wakes with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen squares and system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson's design, using letter shapes similar to the Graffiti writing system on a Palm device. Among the games he devised outside of logic there are a number of word games, including an early version of what today is known as Scrabble. He also appears to have invented, or at least certainly popularised, the Word Ladder (or "doublet" as it was known at first); a form of brain-teaser that is still popular today: the game of changing one word into another by altering one letter at a time, each successive change always resulting in a genuine word. For instance, CAT is transformed into DOG by the following steps: CAT, COT, DOT, DOG. Other items include a rule for finding the day of the week for any date; a means for justifying right margins on a typewriter; a steering device for a velociam (a type of tricycle); new systems of parliamentary representation; more nearly fair elimination rules for tennis tournaments; a new sort of postal money order; rules for reckoning postage; rules for a win in betting; rules for dividing a number by various divisors; a cardboard scale for the college common room he worked in later in life, which, held next to a glass, ensured the right amount of liqueur for the price paid; a double-sided adhesive strip for things like the fastening of envelopes or mounting things in books; a device for helping a bedridden invalid to read from a book placed sideways; and at least two ciphers for cryptography. Mathematical work Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, matrix algebra, mathematical logic and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method) and committees; some of this work was not published until well after his death. He worked as a mathematics tutor at Oxford, an occupation that gave him some financial security. Later years Over the remaining twenty years of his life, throughout his growing wealth and fame, his existence remained little changed. He continued to teach at Christ Church until 1881, and remained in residence there until his death. His last novel, the two-volume Sylvie and Bruno, was published in 1889 and 1893 respectively. It achieved nowhere near the success of the Alice books. Its intricacy was apparently not appreciated by contemporary readers. The reviews and its sales, only 13, copies, were disappointing. The only occasion on which (as far as is known) he travelled abroad was a trip to Russia in 1867 as an ecclesiastical together with the Reverend Henry Liddon. He recounts the travel in his "Russian Journal", which was first commercially published in 1935. On his way to Russia and back Lewis Carroll also saw different cities in Belgium, Germany, the partitioned Poland, and France. He died on 14 January 1898 at his sisters' home, "The Chestnuts" in Guildford, of pneumonia following influenza. He was two weeks away from turning 66 years old. He is buried in Guildford at the Mount Cemetery. Controversies and mysteries "Carroll Myth” Since 1999 a group of scholars, notably Karoline Leach, Hugues Lebailly and Sherry L. Ackerman, John Tufail, Douglas Nickel and others, argue that what Leach terms the "Carroll Myth" has wildly distorted biographical perception of his life and his work. Leach's book, In the Shadow of the Dreamchild, raised a considerable amount of controversy. In brief the claim is that: * In general terms Dodgson's life has been simplified and 'infantilised' by a combination of inaccurate biography and the longstanding unavailability of key evidence, which allowed legends to proliferate unchecked. * By the time the evidence did become available the 'mythic' image of the man had become so embedded in scholastic and popular thinking it remained unquestioned, despite the fact the evidence failed to support it. * If the evidence is examined dispassionately it shows many of the most famous legends about the man (e.g. his 'paedophilia', and his exclusive adoration of small girls) are untrue, or at least grossly simplified. In more detail, Lebailly has endeavoured to set Dodgson's child-photography within the "Victorian Child Cult", which perceived child-nudity as essentially an expression of innocence. Lebailly claims that studies of child nudes were mainstream and fashionable in Dodgson's time and that most photographers, including Oscar Gustave Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameron, made them as a matter of course. Lebailly continues that child nudes even appeared on Victorian Christmas cards, implying a very different social and aesthetic assessment of such material. Lebailly concludes that it has been an error of Dodgson's biographers to view his child-photography with 20th or 21st century eyes, and to have presented it as some form of personal idiosyncrasy, when it was in fact a response to a prevalent aesthetic and philosophical movement of the time. Leach's reappraisal of Dodgson focused in particular on his controversial sexuality. She argues that the allegations of paedophilia rose initially from a misunderstanding of Victorian morals, as well as the mistaken idea, fostered by Dodgson's various biographers, that he had no interest in adult women. She termed the traditional image of Dodgson "the Carroll Myth". She drew attention to the large amounts of evidence in his diaries and letters that he was also keenly interested in adult women, married and single, and enjoyed several scandalous (by the social standards of his time) relationships with them. She also pointed to the fact that many of those he described as "child-friends" were girls in their late teens and even twenties. She argues that suggestions of paedophilia evolved only many years after his death, when his well-meaning family had suppressed all evidence of his relationships with women in an effort to preserve his reputation, thus giving a false impression of a man interested only in little girls. Similarly, Leach traces the claim that many of Carroll's female friendships ended when the girls reached the age of 14 to a 1932 biography by Langford Reed. The concept of the Carroll Myth has produced polarised reactions from Carroll scholars. In 2004 Contrariwise, the Association for new Lewis Carroll studies. was established, and those such as Carolyn Sigler and Cristopher Hollingsworth have joined the ranks of those calling for a major reassessment. But the concept of the Myth has been opposed by some leading Carroll scholars, in particular Morton N. Cohen and Martin Gardner (their comments, and those of more positive reviewers, can be found on Karoline Leach's own page). Biographer Jenny Woolf, while agreeing that Carroll's image has been comprehensively misrepresented in the past, believes that this can be attributed partly to Carroll's own behaviour and in particular his tendency to self-caricature in later life. Ordination Dodgson had been groomed for the ordained ministry in the Anglican Church from a very early age and was expected, as a condition of his residency at Christ Church, to take holy orders within four years of obtaining his master's degree. He delayed the process for some time but eventually took deacon's orders on 22 December 1861. But when the time came a year later to progress to priestly orders, Dodgson appealed to the dean for permission not to proceed. This was against college rules and initially Dean Liddell told him he would have to consult the college ruling body, which would almost undoubtedly have resulted in his being expelled. For unknown reasons, Dean Liddell changed his mind overnight and permitted Dodgson to remain at the college in defiance of the rules. Uniquely amongst senior students of his time Dodgson never became a priest. There is currently no conclusive evidence about why Dodgson rejected the priesthood. Some have suggested his stammer made him reluctant to take the step, because he was afraid of having to preach. Wilson quotes letters by Dodgson describing difficulty in reading lessons and prayers rather than preaching in his own words. But Dodgson did indeed preach in later life, even though not in priest's orders, so it seems unlikely his impediment was a major factor affecting his choice. Wilson also points out that the then Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, who ordained Dodgson, had strong views against clergy going to the theatre, one of Dodgson's great interests. Others have suggested that he was having serious doubts about Anglicanism. He was interested in minority forms of Christianity (he was an admirer of F.D. Maurice) and "alternative" religions (theosophy). Dodgson became deeply troubled by an unexplained sense of sin and guilt at this time (the early 1860s) and frequently expressed the view in his diaries that he was a "vile and worthless" sinner, unworthy of the priesthood, and this sense of sin and unworthiness may well have affected his decision to abandon being ordained to the priesthood. Missing diaries At least four complete volumes and around seven pages of text are missing from Dodgson's 13 diaries. The loss of the volumes remains unexplained; the pages have been deliberately removed by an unknown hand. Most scholars assume the diary material was removed by family members in the interests of preserving the family name, but this has not been proven. Except for one page, the period of his diaries from which material is missing is between 1853 and 1863 (when Dodgson was 21–31 years old). This was a period when Dodgson began suffering great mental and spiritual anguish and confessing to an overwhelming sense of his own sin. This was also the period of time when he composed his extensive love poetry, leading to speculation that the poems may have been autobiographical. Many theories have been put forward to explain the missing material. A popular explanation for one particular missing page (27 June 1863) is that it might have been torn out to conceal a proposal of marriage on that day by Dodgson to the 11-year-old Alice Liddell; there has never been any evidence to suggest this was so, and a paper discovered by Karoline Leach in the Dodgson family archive in 1996 offers some evidence to the contrary. This paper, known as the "cut pages in diary document", was compiled by various members of Carroll's family after his death. Part of it may have been written at the time the pages were destroyed, though this is unclear. The document offers a brief summary of two diary pages that are now missing, including the one for 27 June 1863. The summary for this page states that Mrs. Liddell told Dodgson there was gossip circulating about him and the Liddell family's governess, as well as about his relationship with "Ina", presumably Alice's older sister, Lorina Liddell. The "break" with the Liddell family that occurred soon after was presumably in response to this gossip. An alternative interpretation has been made regarding Carroll's rumoured involvement with "Ina": Lorina was also the name of Alice Liddell's mother. What is deemed most crucial and surprising is that the document seems to imply Dodgson's break with the family was not connected with Alice at all. Until a primary source is discovered, the events of 27 June 1863 remain inconclusive. Migraine and epilepsy In his diary for 1880, Dodgson recorded experiencing his first episode of migraine with aura, describing very accurately the process of 'moving fortifications' that are a manifestation of the aura stage of the syndrome. Unfortunately there is no clear evidence to show whether this was his first experience of migraine per se, or if he may have previously suffered the far more common form of migraine without aura, although the latter seems most likely, given the fact that migraine most commonly develops in the teens or early adulthood. Another form of migraine aura, Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, has been named after Dodgson's little heroine, because its manifestation can resemble the sudden size-changes in the book. Also known as micropsia and macropsia, it is a brain condition affecting the way objects are perceived by the mind. For example, an afflicted person may look at a larger object, like a basketball, and perceive it as if it were the size of a golf ball. Some authors have suggested that Dodgson may have suffered from this type of aura, and used it as an inspiration in his work, but there is no evidence that he did. Dodgson also suffered two attacks in which he lost consciousness. He was diagnosed by three different doctors; a Dr. Morshead, Dr. Brooks, and Dr. Stedman, believed the attack and a consequent attack to be an "epileptiform" seizure (initially thought to be fainting, but Brooks changed his mind). Some have concluded from this he was a lifetime sufferer of this condition, but there is no evidence of this in his diaries beyond the diagnosis of the two attacks already mentioned. Some authors, in particular Sadi Ranson, have suggested Carroll may have suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy in which consciousness is not always completely lost, but altered, and in which the symptoms mimic many of the same experiences as Alice in Wonderland. Carroll had at least one incidence in which he suffered full loss of consciousness and awoke with a bloody nose, which he recorded in his diary and noted that the episode left him not feeling himself for "quite sometime afterward". This attack was diagnosed as possibly "epileptiform" and Carroll himself later wrote of his "seizures" in the same diary. Most of the standard diagnostic tests of today were not available in the nineteenth century. Recently, Dr Yvonne Hart, consultant neurologist at the Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, considered Dodgson's symptoms. Her conclusion, quoted in Jenny Woolf's The Mystery of Lewis Carroll, is that Dodgson very likely had migraine, and may have had epilepsy, but she emphasises that she would have considerable doubt about making a diagnosis of epilepsy without further information. Suggestions of paedophilia Stuart Dodgson Collingwood (Dodgson's nephew and biographer) wrote: And now as to the secondary causes which attracted him to children. First, I think children appealed to him because he was pre-eminently a teacher, and he saw in their unspoiled minds the best material for him to work upon. In later years one of his favourite recreations was to lecture at schools on logic; he used to give personal attention to each of his pupils, and one can well imagine with what eager anticipation the children would have looked forward to the visits of a schoolmaster who knew how to make even the dullest subjects interesting and amusing. Despite comments like this, Dodgson's friendships with young girls and psychological readings of his work – especially his photographs of nude or semi-nude girls – have all led to speculation that he was a paedophile. This possibility has underpinned numerous modern interpretations of his life and work, particularly Dennis Potter's play Alice and his screenplay for the motion picture, Dreamchild, Robert Wilson's Alice, and a number of recent biographies, including Michael Bakewell's Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1996), Donald Thomas's Lewis Carroll: A Portrait with Background (1995), and Morton N. Cohen's Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1995). All of these works more or less unequivocally assume that Dodgson was a paedophile, albeit a repressed and celibate one. Cohen claims Dodgson's "sexual energies sought unconventional outlets", and further writes: We cannot know to what extent sexual urges lay behind Charles's preference for drawing and photographing children in the nude. He contended the preference was entirely aesthetic. But given his emotional attachment to children as well as his aesthetic appreciation of their forms, his assertion that his interest was strictly artistic is naïve. He probably felt more than he dared acknowledge, even to himself. Cohen notes that Dodgson "apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any eroticism", but adds that "later generations look beneath the surface" (p. 229). Cohen and other biographers argue that Dodgson may have wanted to marry the 11-year-old Alice Liddell, and that this was the cause of the unexplained "break" with the family in June 1863. There has never been significant evidence to support the idea, however, and the 1996 discovery of the "cut pages in diary document" (see above) seems to make it highly probable that the 1863 "break" had nothing to do with Alice, but was perhaps connected with rumours involving her older sister Lorina (born 11 May 1849, so she would have been 14 at the time), her governess, or her mother who was also nicknamed "Ina". Some writers, e.g., Derek Hudson and Roger Lancelyn Green, stop short of identifying Dodgson as a paedophile, but concur that he had a passion for small female children and next to no interest in the adult world. The basis for Dodgson's interest in female children has been challenged in the last ten years by several writers and scholars (see the 'Carroll Myth' above). Literary works * La Guida di Bragia, a Ballad Opera for the Marionette Theatre (around 1850) * A Tangled Tale * Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) * Facts * Rhyme? And Reason? (also published as Phantasmagoria) * Pillow Problems * Sylvie and Bruno * Sylvie and Bruno Concluded * The Hunting of the Snark (1876) * Three Sunsets and Other Poems * Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (includes "Jabberwocky" and "The Walrus and the Carpenter") (1871) * What the Tortoise Said to Achilles Mathematical works * A Syllabus of Plane Algebraic Geometry (1860) * The Fifth Book of Euclid Treated Algebraically (1858 and 1868) * An Elementary Treatise on Determinants, With Their Application to Simultaneous Linear Equations and Algebraic Equations * Euclid and his Modern Rivals (1879), both literary and mathematical in style * Symbolic Logic Part I * Symbolic Logic Part II (published posthumously) * The Alphabet Cipher (1868) * The Game of Logic * Some Popular Fallacies about Vivisection * Curiosa Mathematica I (1888) * Curiosa Mathematica II (1892) * The Theory of Committees and Elections, collected, edited, analysed, and published in 1958, by Duncan Black References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Carroll

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet, the son of a farm labourer, who came to be known for his celebratory representations of the English countryside and his lamentation of its disruption. His poetry underwent a major re-evaluation in the late 20th century and he is often now considered to be among the most important 19th-century poets. His biographer Jonathan Bate states that Clare was "the greatest labouring-class poet that England has ever produced. No one has ever written more powerfully of nature, of a rural childhood, and of the alienated and unstable self”. Early life Clare was born in Helpston, six miles to the north of the city of Peterborough. In his life time, the village was in the Soke of Peterborough in Northamptonshire and his memorial calls him "The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Helpston now lies in the Peterborough unitary authority of Cambridgeshire. He became an agricultural labourer while still a child; however, he attended school in Glinton church until he was twelve. In his early adult years, Clare became a pot-boy in the Blue Bell public house and fell in love with Mary Joyce; but her father, a prosperous farmer, forbade her to meet him. Subsequently he was a gardener at Burghley House. He enlisted in the militia, tried camp life with Gypsies, and worked in Pickworth as a lime burner in 1817. In the following year he was obliged to accept parish relief. Malnutrition stemming from childhood may be the main culprit behind his 5-foot stature and may have contributed to his poor physical health in later life. Early poems Clare had bought a copy of Thomson's Seasons and began to write poems and sonnets. In an attempt to hold off his parents' eviction from their home, Clare offered his poems to a local bookseller named Edward Drury. Drury sent Clare's poetry to his cousin John Taylor of the publishing firm of Taylor & Hessey, who had published the work of John Keats. Taylor published Clare's Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery in 1820. This book was highly praised, and in the next year his Village Minstrel and other Poems were published. Midlife He had married Martha ("Patty") Turner in 1820. An annuity of 15 guineas from the Marquess of Exeter, in whose service he had been, was supplemented by subscription, so that Clare became possessed of £45 annually, a sum far beyond what he had ever earned. Soon, however, his income became insufficient, and in 1823 he was nearly penniless. The Shepherd's Calendar (1827) met with little success, which was not increased by his hawking it himself. As he worked again in the fields his health temporarily improved; but he soon became seriously ill. Earl FitzWilliam presented him with a new cottage and a piece of ground, but Clare could not settle in his new home. Clare was constantly torn between the two worlds of literary London and his often illiterate neighbours; between the need to write poetry and the need for money to feed and clothe his children. His health began to suffer, and he had bouts of severe depression, which became worse after his sixth child was born in 1830 and as his poetry sold less well. In 1832, his friends and his London patrons clubbed together to move the family to a larger cottage with a smallholding in the village of Northborough, not far from Helpston. However, he felt only more alienated. His last work, the Rural Muse (1835), was noticed favourably by Christopher North and other reviewers, but this was not enough to support his wife and seven children. Clare's mental health began to worsen. As his alcohol consumption steadily increased along with his dissatisfaction with his own identity, Clare's behaviour became more erratic. A notable instance of this behaviour was demonstrated in his interruption of a performance of The Merchant of Venice, in which Clare verbally assaulted Shylock. He was becoming a burden to Patty and his family, and in July 1837, on the recommendation of his publishing friend, John Taylor, Clare went of his own volition (accompanied by a friend of Taylor's) to Dr Matthew Allen's private asylum High Beach near Loughton, in Epping Forest. Taylor had assured Clare that he would receive the best medical care. Later life and death During his first few asylum years in Essex (1837–1841), Clare re-wrote famous poems and sonnets by Lord Byron. His own version of Child Harold became a lament for past lost love, and Don Juan, A Poem became an acerbic, misogynistic, sexualised rant redolent of an aging Regency dandy. Clare also took credit for Shakespeare's plays, claiming to be the Renaissance genius himself. "I'm John Clare now," the poet claimed to a newspaper editor, "I was Byron and Shakespeare formerly." In 1841, Clare left the asylum in Essex, to walk home, believing that he was to meet his first love Mary Joyce; Clare was convinced that he was married with children to her and Martha as well. He did not believe her family when they told him she had died accidentally three years earlier in a house fire. He remained free, mostly at home in Northborough, for the five months following, but eventually Patty called the doctors in. Between Christmas and New Year in 1841, Clare was committed to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum (now St Andrew's Hospital). Upon Clare's arrival at the asylum, the accompanying doctor, Fenwick Skrimshire, who had treated Clare since 1820, completed the admission papers. To the enquiry "Was the insanity preceded by any severe or long-continued mental emotion or exertion?", Dr Skrimshire entered: "After years of poetical prosing." He remained here for the rest of his life under the humane regime of Dr Thomas Octavius Prichard, encouraged and helped to write. Here he wrote possibly his most famous poem, I Am. He died on 20 May 1864, in his 71st year. His remains were returned to Helpston for burial in St Botolph’s churchyard. Today, children at the John Clare School, Helpston's primary, parade through the village and place their 'midsummer cushions' around Clare's gravestone (which has the inscriptions "To the Memory of John Clare The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet" and "A Poet is Born not Made") on his birthday, in honour of their most famous resident. The thatched cottage where he was born was bought by the John Clare Education & Environment Trust in 2005 and is restoring the cottage to its 18th century state. Poetry In his time, Clare was commonly known as "the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Since his formal education was brief, Clare resisted the use of the increasingly standardised English grammar and orthography in his poetry and prose. Many of his poems would come to incorporate terms used locally in his Northamptonshire dialect, such as 'pooty' (snail), 'lady-cow' (ladybird), 'crizzle' (to crisp) and 'throstle' (song thrush). In his early life he struggled to find a place for his poetry in the changing literary fashions of the day. He also felt that he did not belong with other peasants. Clare once wrote "I live here among the ignorant like a lost man in fact like one whom the rest seemes careless of having anything to do with—they hardly dare talk in my company for fear I should mention them in my writings and I find more pleasure in wandering the fields than in musing among my silent neighbours who are insensible to everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose.” It is common to see an absence of punctuation in many of Clare's original writings, although many publishers felt the need to remedy this practice in the majority of his work. Clare argued with his editors about how it should be presented to the public. Clare grew up during a period of massive changes in both town and countryside as the Industrial Revolution swept Europe. Many former agricultural workers, including children, moved away from the countryside to over-crowded cities, following factory work. The Agricultural Revolution saw pastures ploughed up, trees and hedges uprooted, the fens drained and the common land enclosed. This destruction of a centuries-old way of life distressed Clare deeply. His political and social views were predominantly conservative ("I am as far as my politics reaches 'King and Country'—no Innovations in Religion and Government say I."). He refused even to complain about the subordinate position to which English society relegated him, swearing that "with the old dish that was served to my forefathers I am content." His early work delights both in nature and the cycle of the rural year. Poems such as Winter Evening, Haymaking and Wood Pictures in Summer celebrate the beauty of the world and the certainties of rural life, where animals must be fed and crops harvested. Poems such as Little Trotty Wagtail show his sharp observation of wildlife, though The Badger shows his lack of sentiment about the place of animals in the countryside. At this time, he often used poetic forms such as the sonnet and the rhyming couplet. His later poetry tends to be more meditative and use forms similar to the folks songs and ballads of his youth. An example of this is Evening. His knowledge of the natural world went far beyond that of the major Romantic poets. However, poems such as I Am show a metaphysical depth on a par with his contemporary poets and many of his pre-asylum poems deal with intricate play on the nature of linguistics. His 'bird's nest poems', it can be argued, illustrate the self-awareness, and obsession with the creative process that captivated the romantics. Clare was the most influential poet, aside from Wordsworth to practice in an older style. Revival of interest in the twentieth century Clare was relatively forgotten during the later nineteenth century, but interest in his work was revived by Arthur Symons in 1908, Edmund Blunden in 1920 and John and Anne Tibble in their ground-breaking 1935 2-volume edition. Benjamin Britten set some of 'May' from A Shepherd's Calendar in his Spring Symphony of 1948, and included a setting of The Evening Primrose in his Five Flower Songs Copyright to much of his work has been claimed since 1965 by the editor of the Complete Poetry (OUP, 9 vols., 1984–2003), Professor Eric Robinson though these claims were contested. Recent publishers have refused to acknowledge the claim (especially in recent editions from Faber and Carcanet) and it seems the copyright is now defunct. The John Clare Trust purchased Clare Cottage in Helpston in 2005, preserving it for future generations. In May 2007 the Trust gained £1.m of funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and commissioned Jefferson Sheard Architects to create the new landscape design and Visitor Centre, including a cafe, shop and exhibition space. The Cottage has been restored using traditional building methods and opened to the public. The largest collection of original Clare manuscripts are housed at Peterborough Museum, where they are available to view by appointment. Since 1993, the John Clare Society of North America has organised an annual session of scholarly papers concerning John Clare at the annual Convention of the Modern Language Association of America. Poetry collections by Clare (chronological) * Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. London, 1820. * The Village Minstrel, and Other Poems. London, 1821. * The Shepherd's Calendar with Village Stories and Other Poems. London, 1827 * The Rural Muse. London, 1835. * Sonnet. London 1841 * First Love * Snow Storm. * The Firetail. * The Badger – Time unknown References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Clare

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth (republic) of England under Oliver Cromwell. He wrote at a time of religious flux and political upheaval, and is best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost. Milton's poetry and prose reflect deep personal convictions, a passion for freedom and self determination, and the urgent issues and political turbulence of his day. Writing in English, Latin, and Italian, he achieved international renown within his lifetime, and his celebrated Areopagitica, (written in condemnation of pre-publication censorship) is among history’s most influential and impassioned defenses of free speech and freedom of the press.

Efraín Huerta (Silao, Guanajuato, 18 de junio de 1914 - Ciudad de México, 20 de febrero de 1982). Poeta mexicano. Legado principal El legado principal de Efraín Huerta es el libro Los hombres del alba (1944) que marca una ruptura con las formas poéticas utilizadas hasta ese momento. Es uno de los libros cumbres de la poesía hispanoamericana del siglo veinte. Comienzos Efraín Huerta Romo fue uno de los poetas más reconocidos de México, cuyos versos se caracterizaban por ir en contra de lo establecido en términos estilísticos. Fue además un activista político de la izquierda latinoamericana. Inició sus estudios de derecho en la ciudad de México, pero los abandonó para dedicarse al periodismo y a la literatura. Su primer poemario (Absoluto amor), se caracterizó por su liricismo amoroso, pero tras su vinculación con la revista Taller evolucionó hacia una poesía que reflejaba tanto la subjetividad personal como las circunstancias políticas y sociales. A partir de 1950 inició el movimiento neovanguardista de "El cocodrilismo" por lo que fue conocido como "El gran Cocodrilo". Trayectoria De 1938 a 1941 participó en la publicación de la revista literaria Taller, al lado de sus compañeros universitarios que se dedicaban a las letras (Alberto Quintero Álvarez, Octavio Paz y Rafael Solana, entre otros). Entre los muchos premios que el otorgaron, recibió las Palmas Académicas del gobierno de Francia en 1945, en 1975 el Premio Xavier Villaurrutia,2 el Premio Nacional de Lingüística y Literatura en 1976,3 y el Premio Nacional de Periodismo en divulgación cultural de 1978 por su trabajo en el suplemento El Gallo Ilustrado del periódico El Día.4 Fue uno de los periodistas cinematográficos más importantes de México y sus columnas aparecieron en prácticamente todas las revistas especializadas de las décadas de 1940 y 1950. Sus columnas de tema literario y político aparecieron también en los principales diarios del país desde los años treinta hasta 1982, año de su muerte. Obra poética Su poesía fue reunida en un tomo de más de seiscientas páginas editado por Martí Soler y publicado por el Fondo de Cultura Económica en 1988. * 1935 - Absoluto amor * 1936 - Línea del alba * 1944 - Los hombres del alba * 1943 - Poemas de guerra y esperanza * 1950 - La rosa primitiva * 1951 - Poesía * 1953 - Poemas de viaje * 1956 - Estrella en alto y nuevos poemas * 1957 - Para gozar tu paz * 1959 - ¡Mi país, oh mi país! * 1959 - Elegía de la policía montada * 1961 - Farsa trágica del presidente que quería una isla * 1962 - La raíz amarga * 1963 - El Tajín * 1973 - Poemas prohibidos y de amor * 1974 - Los eróticos y otros poemas * 1980 - Estampida de poemínimos * 1980 - Transa poética * 1985 - Estampida de Poemínimos Entre sus muchos poemas destacan sus Poemínimos, diminutos poemas parecidos a los haikus, entre ellos el titulado Pequeño Larousse, que habla de lo que dice su entrada en dicho diccionario enciclopédico: "...Nació En Silao. 1914. Autor De versos De contenido Social..." Embustero Larousse. Yo sólo Escribo Versos De contenido Sexual. Y el titulado Tótem: Tótem Siempre Amé Con la Furia Silenciosa De un Cocodrilo Aletargado Referencias Wikipedia - http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Efraín_Huerta

Jorge Guillén Álvarez (Valladolid, 18 de enero de 1893 - Málaga, 6 de febrero de 1984) fue un poeta y crítico literario español de la Generación del 27. Nació en Valladolid, donde residió durante su infancia y su juventud. Siempre dijo que "era de Valladolid". Estudió sus primeras letras y Bachillerato en su ciudad natal y, aunque comenzó Filosofía y Letras en Madrid alojado en la Residencia de Estudiantes, se licenció en la Universidad de Granada. Desde 1909 hasta 1911 vivió en Suiza. Su vida transcurrió paralela a la de su amigo Pedro Salinas, a quien sucedió como lector de español en La Sorbona desde 1917 a 1923.