Info

Noche estrellada sobre el Ródano

Vincent van Gogh

1888

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Gregory Nunzio Corso (March 26, 1930– January 17, 2001) was an American poet, youngest of the inner circle of Beat Generation writers (with Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs). Early life Born Nunzio Corso at St. Vincent’s hospital (later called the Poets’ hospital after Dylan Thomas died there), Corso later selected the name “Gregory” as a confirmation name. Within Little Italy and its community he was “Nunzio,” while he dealt with others as “Gregory.” He often would use “Nunzio” as short for “Annunziato,” the announcing angel Gabriel, hence a poet. Corso identified with not only Gabriel but also the Greco-Roman God Hermes, the divine messenger. Corso’s mother, Michelina Corso (born Colonna) was born in Miglianico, Abruzzo, Italy, and immigrated to the United States at the age of nine, with her mother and four other sisters. At 16, she married Sam Corso, a first-generation Italian American, also teenage, and gave birth to Nunzio Corso the same year. They lived at the corner of Bleecker and MacDougal, the heart of Greenwich Village and upper Little Italy. Childhood Sometime in his first year, Corso’s mother mysteriously abandoned him, leaving him at the New York Foundling Home, a branch of the Catholic Church Charities. Corso’s father, Sam “Fortunato” Corso, a gruff garment center worker, found the infant and promptly put him in a foster home. Michelina came to New York but her life was threatened by Sam. One of Michelina’s sisters was married to a New Jersey mobster who offered to give Michelina her “vengeance,” that is to kill Sam. Michelina declined and returned to Trenton without her child. Sam consistently told Corso that his mother had returned to Italy and deserted the family. He was also told that she was a prostitute and was “disgraziata” (disgraced) and forced into Italian exile. Sam told the young boy several times, “I should have flushed you down the toilet.” It was 67 years before Corso learned the truth of his mother’s disappearance. Corso spent the next 11 years in foster care in at least five different homes. His father rarely visited him. When he did, Corso was often abused: “I’d spill jello and the foster home people would beat me. Then my father would visit and he’d beat me again—a double whammy.” As a foster child, Corso was among thousands that the Church aided during the Depression, with the intention of reconstituting families as the economy picked up. Corso went to Catholic parochial schools, was an altar boy and a gifted student. His father, in order to avoid the military draft, brought Gregory home in 1941. Nevertheless, Sam Corso was drafted and shipped overseas. Corso, then alone, became a homeless child on the streets of Little Italy. For warmth he slept in subways in the winter, and then slept on rooftops during the summer. He continued to attend Catholic school, not telling authorities he was living on the streets. With “permission,” he stole breakfast bread from Vesuvio Bakery, 160 Prince Street in Little Italy. Street food stall merchants would give him food in exchange for running errands. Adolescence At age 13, Corso was asked to deliver a toaster to a neighbor. While he was running the errand, a passerby offered money for the toaster, and Corso sold it. He used the money to buy a tie and white shirt, and dressed up to see the film The Song of Bernadette, about the mystical appearance of the Virgin Mary to Bernadette Soubirous at Lourdes. On returning from the movie, the police apprehended him. Corso claimed he was seeking a miracle, namely, to find his mother. Corso had a lifelong affection for saints and holy men: “They were my only heroes.” Nonetheless, he was arrested for petty larceny and incarcerated in The Tombs, New York’s infamous jail. Corso, even though only thirteen years old, was celled next to an adult, criminally insane murderer who had stabbed his wife repeatedly with a screwdriver. The exposure left Corso traumatized. Neither Corso’s stepmother nor his paternal grandmother would post his $50 bond. With his own mother missing and unable to make bail, he remained in the Tombs. Later, in 1944 during a New York blizzard, a 14-year-old freezing Corso broke into his tutor’s office for warmth, and fell asleep on a desk. He slept through the blizzard and was arrested for breaking and entering and booked into the Tombs a second time, with adults. Terrified of other inmates, he was sent to the psychiatric ward of Bellevue Hospital Center and later released. At the age of seventeen, on the eve of his eighteenth birthday, Corso broke into a tailor shop and stole an over-sized suit to dress for a date. Police records indicate he was arrested two blocks from the shop. He spent the night in the Tombs and was arraigned the next morning as an 18-year-old with prior offenses. No longer a “youthful offender,” he was given a two to three years sentence to Clinton State Prison, in Dannemora, New York, on the Canadian border. It was New York’s toughest prison, the site of the state’s electric chair. Corso always has expressed a curious gratitude for Clinton making him a poet. His second book of poems, Gasoline, is dedicated to “the angels of Clinton Prison who, in my seventeenth year, handed me, from all the cells surrounding me, books of illumination.” Interestingly, Clinton later became known as the “poets’ prison,” as rap poets served time there. Corso at Clinton Correctional While being transported to Clinton, Corso, terrified of prison and the prospect of rape, concocted a story of why he was sent there. He told hardened Clinton inmates he and two friends had devised the wild plan of taking over New York City by means of walkie-talkies, projecting a series of improbable and complex robberies. Communicating by walkie-talkie, each of the three boys took up an assigned position—one inside the store to be robbed, one outside on the street to watch for the police, and a third, Corso, the master-planner, in a small room nearby dictating the orders. According to Corso, he was in the small room giving the orders when the police came. In light of Corso’s youth, his imaginative yarn earned him bemused attention at Clinton. Richard Biello, a Capo, asked Corso who he was connected with, that is, what New York crime family did he come from, talking such big crimes as walkie-talkie robberies...,"I’m independent!" Corso shot back, hoping to keep his distance from the Mob inmates. A week later, in the prison showers, Corso was grabbed by a handful of inmates, and the 18-year-old was about to be raped. Biello happened in and commented, “Corso! You don’t look so independent right now.” Biello waved off the would-be rapists, who were afraid of Mafia reprisals. Thus Corso fell under the protection of powerful Mafioso inmates, and became something of a mascot because he was the youngest inmate in the prison, and he was entertaining. Corso would cook the steaks and veal brought from the outside by Mafia underlings in the “courts”—55-gallon-barrel barbecues and picnic tables—assigned to the influential prisoners. Clinton also had a ski run right in the middle of “the yards,” and Corso learned to downhill ski and taught the Mafiosi. He entertained his mobster elders as a court jester, quick with ripostes and jokes. Corso would often cite the three propositions given him by a Mafia capo: "1) Don’t serve time, let time serve you. 2) Don’t take your shoes off because with a 2 -3 you’re walking right out of here. 3) When you’re in the yard talking to three guys, see four. See yourself. Dig yourself.” Interestingly, Corso was jailed in the very cell just months before vacated by Charles “Lucky” Luciano. While imprisoned, Luciano had donated an extensive library to the prison. The cell was also equipped with a phone and self-controlled lighting as Luciano was, from prison, cooperating with the U.S. Government’s wartime effort, providing Mafia aid in policing the New York waterfront, and later helping in Naples, Italy through his control of the Camorra. In this special cell, Corso read after lights-out thanks to a light specially positioned for Luciano to work late. Corso was encouraged to read and study by his Cosa Nostra mentors, who recognized his genius. There, Corso began writing poetry. He studied the Greek and Roman classics, and consumed encyclopedias and dictionaries. He credited the The Story of Civilization, Will and Ariel Durant’s ground-breaking compendium of history and philosophy, for his general education and philosophical sophistication. Release and return to New York City In 1951, 21-year-old Gregory Corso worked in the garment center by day, and at night was a mascot yet again, this time at one of Greenwich Village’s first lesbian bars, the Pony Stable Inn. The women gave Corso a table at which he wrote poetry. One night a Columbia College student, Allen Ginsberg, happened into the Pony Stable and saw Corso... “he was good looking, and wondered if he was gay, or what.” Corso, who was definitely not gay, was not uncomfortable with same sex come-ons after his time in prison, and thought he could score a beer off Ginsberg. He showed Ginsberg some of the poems he was writing, a number of them from prison, and Ginsberg immediately recognized Corso as “spiritually gifted.” One poem described a woman who sunbathed in a window bay across the street from Corso’s room on 12th Street. Astonishingly, the woman happened to be Ginsberg’s erstwhile girl friend, with whom he lived in one of his rare forays into heterosexuality. Ginsberg invited Corso back to their apartment and asked the woman if she would satisfy Corso’s sexual curiosity. She agreed, but Corso, still a virgin, got too nervous as she disrobed, and he ran from the apartment, struggling with his pants. Ginsberg and Corso became fast friends. All his life, Ginsberg had a sexual attraction to Corso, which remained unrequited. Corso joined the Beat circle and was adopted by its co-leaders, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, who saw in the young street-wise writer a potential for expressing the poetic insights of a generation wholly separate from those preceding it. At this time he developed a crude and fragmented mastery of Shelley, Marlowe, and Chatterton. Shelley’s “A Defence of Poetry” (1840), with its emphasis on the ability of genuine poetic impulse to stimulate “unapprehended combinations of thought” that led to the “moral improvement of man,” prompted Corso to develop a theory of poetry roughly consistent with that of the developing principles of the Beat poets. For Corso, poetry became a vehicle for change, a way to redirect the course of society by stimulating individual will. He referred to Shelley often as a “Revolutionary of Spirit”, which he considered Ginsberg and himself to be. Cambridge In 1954, Corso moved to Cambridge, where several important poets, including Edward Marshall and John Wieners, were experimenting with the poetics of voice. The center for Corso’s life there was not “the School of Boston,” as these poets were called, but Harvard University’s Widener Library, where he spent his days reading the great works of poetry and also auditing classes in the Greek and Roman Classics. Corso’s appreciation of the classics had come from the Durants’ books that he had read in prison. At Harvard he considered becoming a classics scholar. Corso, penniless, lived on a dorm room floor in Elliott house, welcomed by students Peter Sourian, Bobby Sedgwick (brother of Edie), and Paul Grand. He would dress up for dinner and not be noticed. Members of the elite Porcellian Club reported Corso to the Harvard administration as an interloper. Dean Archibald MacLeish met with Corso intending to expel him, but Corso showed him his poems and MacLeish relented and allowed Corso to be a non-matriculating student—a poet in residence. Corso’s first published poems appeared in the Harvard Advocate in 1954, and his play In This Hung-up Age—concerning a group of Americans who, after their bus breaks down midway across the continent, are trampled by buffalo—was performed by the esteemed Poets’ Theater the following year, along with T.S. Eliot’s “Murder in the Cathedral.” Harvard and Radcliffe students, notably Grand, Sourian and Sedgwick, underwrote the printing expenses of Corso’s first book, The Vestal Lady on Brattle, and Other Poems. The poems featured in the volume are usually considered apprentice work heavily indebted to Corso’s reading. They are, however, unique in their innovative use of jazz rhythms—most notably in “Requiem for 'Bird’ Parker, musician,” which many call the strongest poem in the book—cadences of spoken English, and hipster jargon. Corso once explained his use of rhythm and meter in an interview with Gavin Selerie for Riverside Interviews: “My music is built in—it’s already natural. I don’t play with the meter.” In other words, Corso believes the meter must arise naturally from the poet’s voice; it is never consciously chosen. In a review of The Vestal Lady on Brattle for Poetry, Reuel Denney asked whether “a small group jargon” such as bop language would “sound interesting” to those who were not part of that culture. Corso, he concluded, “cannot balance the richness of the bebop group jargon... with the clarity he needs to make his work meaningful to a wider-than-clique audience.” Ironically, within a few years, that “small group jargon”, the Beat lingo, became a national idiom, featuring words such as “man,” “cool,” “dig,” “chick,” “hung up,” etc. Despite Corso’s reliance on traditional forms and archaic diction, he remained a street-wise poet, described by Bruce Cook in The Beat Generation as “an urchin Shelley.” Biographer Carolyn Gaiser suggested that Corso adopted “the mask of the sophisticated child whose every display of mad spontaneity and bizarre perception is consciously and effectively designed”—as if he is in some way deceiving his audience. But the poems at their best are controlled by an authentic, distinctive, and enormously effective voice that can range from sentimental affection and pathos to exuberance and dadaist irreverence toward almost anything except poetry itself. San Francisco, “Howl”, and the Beat Phenomenon Corso and Ginsberg decided to head to San Francisco, separately. Corso wound up temporarily in Los Angeles and worked at the L.A. Examiner news morgue. Ginsberg was delayed in Denver. They were drawn by reports of an iconoclast circle of poets, including Gary Snyder, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael McClure, Philip Whalen and Lew Welch. An older literary mentor, the socialist writer Kenneth Rexroth, lent his apartment as a Friday-night literary salon (Ginsberg’s mentor William Carlos Williams, an old friend of Rexroth’s, had given him an introductory letter). Wally Hedrick [13] wanted to organize the famous Six Gallery reading, and Ginsberg wanted Rexroth to serve as master of ceremonies, in a sense to bridge generations. Philip Lamantia, Michael McClure, Philip Whalen, Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder read on October 7, 1955, before 100 people (including Kerouac, up from Mexico City). Lamantia read poems of his late friend John Hoffman. At his first public reading Ginsberg performed the just-finished first part of “Howl.” Gregory Corso arrived late the next day, missing the historic reading, at which he had been scheduled to read. The Six Gallery was a success, and the evening led to many more readings by the now locally famous Six Gallery poets. It was also a marker of the beginning of the West Coast Beat movement, since the 1956 publication of Howl (City Lights Pocket Poets, no. 4) and its obscenity trial in 1957 brought it to nationwide attention. Ginsberg and Corso hitchhiked from San Francisco, visiting Henry Miller in Big Sur, and stopped off in Los Angeles. As guests of Anaïs Nin and writer Lawrence Lipton, Corso and Ginsberg gave a reading to a gathering of L.A. literati. Ginsberg took the audience off-guard, by proclaiming himself and Corso as poets of absolute honesty, and they both proceeded to strip bare naked of clothes, shocking even the most avant-garde of the audience. Corso and Ginsberg then hitchhiked to Mexico City to visit Kerouac who was holed up in a room above a whorehouse, writing a novel, “Tristessa.” After a three-week stay in Mexico City, Ginsberg left, and Corso waited for a plane ticket. His lover, Hope Savage, convinced her father, Henry Savage Jr., the mayor of Camden, S.C., to send Corso a plane ticket to Washington, D.C. Corso had been invited by the Library of Congress poet (precursor to U.S. Poet Laureate) Randall Jarrell and his wife Mary, to live with them, and become Jarrell’s poetic protege. Jarrell, unimpressed with the other Beats, found Corso’s work to be original and believed he held great promise. Corso stayed with the Jarrells for two months, enjoying the first taste of family life ever. However, Kerouac showed up and crashed at the Jarrells’, often drunk and loud, and got Corso to carouse with him. Corso was disinvited by the Jarrells and returned to New York. To Paris and the “Beat Hotel” In 1957, Allen Ginsberg voyaged with Peter Orlovsky to visit William S. Burroughs in Morocco. They were joined by Kerouac, who was researching the French origins of his family. Corso, already in Europe, joined them in Tangiers and, as a group, they made an ill-fated attempt to take Burroughs’ fragmented writings and organize them into a text (which later would become Naked Lunch). Burroughs was strung out on heroin and became jealous of Ginsberg’s unrequited attraction for Corso, who left Tangiers for Paris. In Paris, Corso introduced Ginsberg and Orlovsky to a Left Bank lodging house above a bar at 9 rue Gît-le-Coeur, that he named the Beat Hotel. They were soon joined by William Burroughs and others. It was a haven for young expatriate painters, writers and musicians. There, Ginsberg began his epic poem Kaddish, Corso composed his poems Bomb and Marriage, and Burroughs (with Brion Gysin’s help) put together Naked Lunch from previous writings. This period was documented by the photographer Harold Chapman, who moved in at about the same time, and took pictures of the residents of the hotel until it closed in 1963. Corso’s Paris sojourn resulted in his third volume of poetry, The Happy Birthday of Death (1960), Minutes to Go (1960, visual poetry deemed “cut-ups”) with William S. Burroughs, Sinclair Beiles, and Brion Gysin, The American Express (1961, an Olympia Press novel), and Long Live Man (1962, poetry). Corso fell out with his publisher of Gasoline, Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights Bookstore, who objected to “Bomb,” a position Ferlinghetti later rued and for which he apologized. Corso’s work found a strong reception at New Directions Publishing, founded by James Laughlin, who had heard of Corso through Harvard connections. New Directions was considered the premier publisher of poetry, with Ezra Pound, Dylan Thomas, Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, Thomas Merton, Denise Levertov, James Agee, and ironically, Lawrence Ferlinghetti. While in Europe Corso searched for his lover, Hope Savage, who had disappeared from New York, saying she was headed to Paris. He visited Rome and Greece, sold encyclopedias in Germany, hung out with jazz trumpeter Chet Baker in Amsterdam, and with Ginsberg set the staid Oxford Union in turmoil with his reading of “Bomb,” which the Oxford students mistakenly believed was pro-nuclear war (as had Ferlinghetti), while they and other campuses were engaged in “ban the bomb” demonstrations. A student threw a shoe at Corso, and both he and Ginsberg left before Ginsberg could read “Howl.” Corso returned to New York in 1958, amazed that he and his compatriots had become famous, or notorious, emerging literary figures. Return to New York– The “Beatniks” In late 1958, Corso reunited with Ginsberg and Orlovsky. They were astonished that before they left for Europe they had sparked a social movement, which San Francisco columnist Herb Caen called, “Beat-nik,” combining “beat” with the Russian “Sputnik,” as if to suggest that the Beat writers were both “out there” and vaguely Communist. San Francisco’s obscenity trial of Lawrence Ferlinghetti for publishing Ginsberg’s “Howl” had ended in an acquittal, and the national notoriety made “The Beats” famous, adored and ridiculed. Upon their return, Ginsberg, Corso, Kerouac and Burroughs were published in the venerable Chicago Review, but before the volume was sold, University of Chicago President Robert Hutchins deemed it pornographic and had all copies confiscated. The Chicago editors promptly resigned and started an alternative literary magazine, The Big Table. Ginsberg and Corso took a bus from New York for the “Big Table” launch, which again propelled them into the national spotlight. Studs Terkel’s interview of the two was a madcap romp which set off a wave of publicity. Controversy followed them and they relished making the most of their outlaw and pariah image. Time and Life magazines had a particular dislike of the two, hurling invective and insult that Corso and Ginsberg hoped they could bootstrap into yet more publicity. The Beat Generation (so named by Kerouac) was galvanized and young people began dressing with berets, toreador pants, and beards, and carrying bongos. Corso would quip that he never grew a beard, didn’t own a beret, and couldn’t fathom bongos. Corso and Ginsberg traveled widely to college campuses, reading together. Ginsberg’s “Howl” provided the serious fare and Corso’s “Bomb” and “Marriage” provided the humor and bonhomie. New York’s Beat scene erupted and spilled over to the burgeoning folk music craze in the Village, Corso’s and Ginsberg’s home ground. An early participant was a newly arrived Bob Dylan: “I came out of the wilderness and just fell in with the Beat scene, the Bohemian, the Be Bop crowd. It was all pretty connected.” “It was Jack Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso, Ferlinghetti... I got in at the tail end of that and it was magic.” –Bob Dylan in America. Corso also published in the avant garde little magazine Nomad at the beginning of the 1960s. During the early 1960s Corso married Sally November, an English teacher who grew up in Cleveland, Ohio and attended Shaker High School, and graduated from the University of Michigan. At first, Corso mimicked “Marriage” and moved to Cleveland to work in Sally’s father’s florist shop. Then the couple lived in Manhattan and Sally was known to Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Larry Rivers and others in the beat circle at that time. The marriage, while a failure, did produce a child, Miranda Corso. Corso maintained contact with Sally and his daughter sporadically during his lifetime. Sally, who subsequently remarried, resides on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and has kept contact with one of the iconic females associated with the Beat movement, Hettie Jones. Corso married two other times and had sons and a daughter. As the Beats were supplanted in the 1960s by the Hippies and other youth movements, Corso experienced his own wilderness years. He struggled with alcohol and drugs. He later would comment that his addictions masked the pain of having been abandoned and emotionally deprived and abused. Poetry was his purest means of transcending his traumas, but substance abuse threatened his poetic output. He lived in Rome for many years, and later married in Paris and taught in Greece, all the while traveling widely. He strangely remained close to the Catholic Church as critic and had a loose identification as a lapsed Catholic. His collection Dear Fathers was several letters commenting on needed reforms in the Vatican. In 1969, Corso published a volume, Elegiac Feelings American, whose lead poem, dedicated to the recently deceased Jack Kerouac, is regarded by some critics as Corso’s best poem. In 1981 he published poems mostly written while residing in Europe, entitled Herald of the Autochthonic Spirit. In 1972, Rose Holton and her sister met Corso on the second day of their residence at the Chelsea Hotel in New York City: “He sold us on the Chelsea and sold us on himself. Everything that life can throw at you was reflected in his very being. It was impossible for him to be boring. He was outrageous, always provocative, alternately full of indignation or humor, never censoring his words or behavior. But the main thing is that Gregory was authentic. He could play to the audience, but he was never a phony poseur. He was the real deal. He once explained the trajectory of creative achievement: ”There is talent, there is genius, then there is the divine." Gregory inhabited the divine.” Poetry Corso’s first volume of poetry The Vestal Lady on Brattle was published in 1955 (with the assistance of students at Harvard, where he had been auditing classes). Corso was the second of the Beats to be published (after only Kerouac’s The Town and the City), despite being the youngest. His poems were first published in the Harvard Advocate. In 1958, Corso had an expanded collection of poems published as number 8 in the City Lights Pocket Poets Series: Gasoline & The Vestal Lady on Brattle. Of his many notable poems are the following: “Bomb” (a “concrete poem” formatted in typed paper slips of verse, arranged in the shape of a mushroom cloud), “Elegiac Feelings American” of the recently deceased Jack Kerouac, and “Marriage,” a humorous meditation on the institution, perhaps his signature poem. And later in life, “The Whole Mess Almost.” “Marriage” excerpt: Should I get married? Should I be good? Astound the girl next door with my velvet suit and faustus hood? Don’t take her to movies but to cemeteries tell all about werewolf bathtubs and forked clarinets then desire her and kiss her and all the preliminaries and she going just so far and I understanding why not getting angry saying You must feel! It’s beautiful to feel! Instead take her in my arms lean against an old crooked tombstone and woo her the entire night the constellations in the sky— When she introduces me to her parents back straightened, hair finally combed, strangled by a tie, should I sit knees together on their 3rd degree sofa and not ask Where’s the bathroom? How else to feel other than I am, often thinking Flash Gordon soap— O how terrible it must be for a young man seated before a family and the family thinking We never saw him before! He wants our Mary Lou! After tea and homemade cookies they ask What do you do for a living? Should I tell them? Would they like me then? Say All right get married, we’re losing a daughter but we’re gaining a son— And should I then ask Where’s the bathroom? O God, and the wedding! All her family and her friends and only a handful of mine all scroungy and bearded just wait to get at the drinks and food— In “Marriage,” Corso tackles the possibilities of marriage. It was among his “title poems,” with “Power,” “Army,” and others that explore a concept. “Should I get married?” (1), the speaker begins. Could marriage bring about the results that the speaker is looking for? Coming “home to her” (54) and sitting "by the fireplace and she in the kitchen/aproned young and lovely wanting my baby/ and so happy about me she burns the roast beef" (55–57). Idealizing marriage and fatherhood initially, Corso’s speaker embraces reality in the second half of the poem admitting, “No, I doubt I’d be that kind of father” (84). Recognizing that the act of marriage is in itself a form of imprisonment, “No, can’t imagine myself married to that pleasant prison dream” (103), Corso’s speaker acknowledges in the end that the possibility of marriage is not promising for him. Bruce Cook from the book The Beat Generation illuminates Corso’s skill at juxtaposing humor and serious critical commentary, “Yet as funny and entertaining as all this certainly is, it is not merely that, for in its zany way ‘Marriage’ offers serious criticism of what is phony about a sacred American institution.” Corso’s sometimes surreal word mash-ups—"forked clarinets," “Flash Gordon soap,” “werewolf bathtubs”—caught the attention of many. It was “Bomb” and “Marriage” that caught the eye of a young Bob Dylan, still in Minnesota. Dylan said, “The Gregory Corso poem 'Bomb’ was more to the point and touched the spirit of the times better—a wasted world and totally mechanized—a lot of hustle and bustle—a lot of shelves to clean, boxes to stack. I wasn’t going to pin my hopes on that.” The poem “Bomb” created controversy because Corso mixed humor and politics. The poem was initially misinterpreted by many as being supportive of nuclear war. The opening lines of the poem tend to lead the reader to believe that Corso supported the bomb. He writes, "You Bomb /Toy of universe Grandest of all snatched-sky I cannot hate you [extra spaces Corso’s]" (lines 2–3). The speaker goes on to state that he cannot hate the bomb just as he cannot hate other instruments of violence, such as clubs, daggers, and St. Michael’s burning sword. He continues on to point out that people would rather die by any other means including the electric chair, but death is death no matter how it happens. The poem moves on to other death imagery and at time becomes a prayer to the bomb. The speaker offers to bring mythological roses, a gesture that evokes an image of a suitor at the door. The other suitors courting the bomb include Oppenheimer and Einstein, scientists who are responsible for the creation of the bomb. He concludes the poem with the idea that more bombs will be made "and they’ll sit plunk on earth’s grumpy empires/ fierce with moustaches of gold" (lines 87–8). Christine Hoff Kraemer states the idea succinctly, “The bomb is a reality; death is a reality, and for Corso, the only reasonable reaction is to embrace, celebrate, and laugh with the resulting chaos” (212). Kraemer also asserts, “Corso gives the reader only one clue to interpreting this mishmash of images: the association of disparate objects is always presented in conjunction with the exploding bomb” (214). In addition she points to Corso’s denial that the poem contained political significance. In contrast to Corso’s use of marriage as a synecdoche for a Beat view of women, postmodern feminist poet Hedwig Gorski chronicles a night with Corso in her poem “Could not get Gregory Corso out of my Car” (1985, Austin, Texas) showing the womanizing typical for heterosexual Beat behavior. Gorski criticizes the Beat movement for tokenism towards women writers and their work, with very few exceptions, including Anne Waldman, and post-beats like Diane DiPrima and herself. Male domination and womanizing by its heterosexual members, along with tokenism by its major homosexual members characterize the Beat Literary Movement. Beats scoffed at the Feminist Movement which offered liberalizing social and professional views of women and their works as did the Beat Movement for men, especially homosexuals. Corso however always defended women’s role in the Beat Generation, often citing his lover, Hope Savage, as a primary influence on him and Allen Ginsberg. Ted Morgan described Corso’s place in the beat literary world: “If Ginsberg, Kerouac and Burroughs were the Three Musketeers of the movement, Corso was their D’Artagnan, a sort of junior partner, accepted and appreciated, but with less than complete parity. He had not been in at the start, which was the alliance of the Columbia intellectuals with the Times Square hipsters. He was a recent adherent, although his credentials were impressive enough to gain him unrestricted admittance ...” It has taken 50 years and the death of the other Beats, for Corso to be fully appreciated as a poet of equal stature and significance. Later years In later years, Corso disliked public appearances and became irritated with his own “Beat” celebrity. He never allowed a biographer to work in any “authorized” fashion, and only posthumously was a volume of letters published under the specious artifice of An Accidental Autobiography. He did, however, agree to allow filmmaker Gustave Reininger to make a cinema vérité documentary, Corso: The Last Beat, about him. Corso had a cameo appearance in The Godfather III where he plays an outraged stockholder trying to speak at a meeting. After Allen Ginsberg’s death, Corso was depressed and despondent. Gustave Reininger convinced him to go “on the road” to Europe and retrace the early days of “the Beats” in Paris, Italy and Greece. While in Venice, Corso expressed on film his lifelong concerns about not having a mother and living such an uprooted childhood. Corso became curious about where in Italy his mother, Michelina Colonna, might be buried. His father’s family had always told him that his mother had returned to Italy a disgraced woman, a whore. Filmmaker Gustave Reininger quietly launched a search for Corso’s mother’s Italian burial place. In an astonishing turn of events, Reininger found Corso’s mother Michelina not dead, but alive; and not in Italy, but in Trenton, New Jersey. Corso was reunited with his mother on film. He discovered that she at the age of 17 had been almost fatally brutalized (all her front teeth punched out) and was sexually abused by her teenage husband, his father. On film, Michelina explained that, at the height of the Depression, with no trade or job, she had no choice but to give her son into the care of Catholic Charities. After she had established a new life working in a restaurant in New Jersey, she had attempted to find him, to no avail. The father, Sam Corso, had blocked even Catholic Charities from disclosing the boy’s whereabouts. Living modestly, she lacked the means to hire a lawyer to find her son. She worked as a waitress in a sandwich shop in the New Jersey State Office Building in Trenton. She eventually married the cook, Paul Davita, and started a new family. Her child Gregory remained a secret between Michelina and her mother and sisters, until Reininger found them. Corso and his mother quickly developed a relationship which lasted until his death, which preceded hers. They both spent hours on the phone, and the initial forgiveness displayed in the film became a living reality. Corso and Michelina loved to gamble and on several occasions took vacations to Atlantic City for blackjack at the casinos. Corso always lost, while Michelina fared better and would stake him with her winnings. Corso claimed that he was healed in many ways by meeting his mother and saw his life coming full circle. He began to work productively on a new, long-delayed volume of poetry, The Golden Egg. Shortly thereafter, Corso discovered he had irreversible prostate cancer. He died of the disease in Minnesota on January 17, 2001. Around two hundred people were present in the so-called “English Cemetery” in Rome, Italy, on Saturday morning, May 5, to pay their last respects to Gregory Corso. The poet’s ashes were buried in a tomb precisely in front of the grave of his great colleague Shelley, and not far from the one of John Keats. In the tranquillity of this small and lovely cemetery, full of trees, flowers and well-fed cats, with the sun’s complicity, more than a funeral, it seemed to be a reunion of long-lost friends, with tales, anecdotes, laughter and poetry readings. The urn bearing Corso’s ashes arrived with his daughter Sheri Langerman who had assisted him during the last seven months of his life. Twelve other Americans came with her, among them Corso’s old friends Roger Richards and the lawyer Robert Yarra. The cemetery had been closed to newcomers since the mid-century and Robert Yarra and Hannelore deLellis made it possible for Corso to be buried there. (Corso was a Catholic and the cemetery was strictly Protestant, but an exception was made for Corso.) His ashes were deposited at the foot of the grave of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in the Cimitero Acattolico, the Protestant Cemetery, Rome. He wrote his own epitaph: Spirit is Life It flows thru the death of me endlessly like a river unafraid of becoming the sea Quotes “…a tough young kid from the Lower East Side who rose like an angel over the roof tops and sang Italian song as sweet as Caruso and Sinatra, but in words.… Amazing and beautiful, Gregory Corso, the one and only Gregory, the Herald."—Jack Kerouac– Introduction to Gasoline “Corso’s a poet’s Poet, a poet much superior to me. Pure velvet... whose wild fame’s extended for decades around the world from France to China, World Poet.—Allen Ginsberg, ”On Corso’s Virtues” “Gregory’s voice echoes through a precarious future.... His vitality and resilience always shine through, with a light that is more than human: the immortal light of his Muse.... Gregory is indeed one of the Daddies.”—William S. Burroughs “The most important of the beat poets... a really true poet with an original voice”—Nancy Peters, editor of City Lights “Other than Mr. Corso, Gregory was all you ever needed to know. He defined the name by his every word or act. Always succinct, he never tried. Once he called you 'My Ira’ or 'My Janine’ or ‘My Allen,’ he was forever 'Your Gregory’.”—Ira Cohen “...It comes, I tell you, immense with gasolined rags and bits of wire and old bent nails, a dark arriviste, from a dark river within.”– Gregory Corso, How Poetry Comes to Me (epigraph of Gasoline) “They, that unnamed ”they", they’ve knocked me down but I got up. I always get up-and I swear when I went down quite often I took the fall; nothing moves a mountain but itself. They, I’ve long ago named them me."– Gregory Corso Bibliography * The Vestal Lady and Other Poems (1955, poetry) * This Hung-Up Age (1955, play) * Gasoline (1958, poetry) * Bomb (1958, poetry) * The Happy Birthday of Death (1960, poetry) * Minutes to Go (1960, visual poetry) with Sinclair Beiles, William S. Burroughs, and Brion Gysin. * The American Express (1961, novel) * Long Live Man (1962, poetry) * There is Yet Time to Run Back through Life and Expiate All That’s been Sadly Done (1965, poetry) * Elegiac Feelings American (1970, poetry) * The Night Last Night was at its Nightest (1972, poetry) * Earth Egg (1974, poetry) * Writings from OX (1979, with interview by Michael Andre) * Herald of the Autochthonic Spirit (1981, poetry) * Mind Field (1989, poetry) * Mindfield: New and Selected Poems (1989, poetry) * King Of The Hill: with Nicholas Tremulis (1993, album)[16] * Bloody Show: with Nicholas Tremulis (1996, album)[17] * The Whole Shot: Collected Interviews with Gregory Corso (2015) * Sarpedon: A Play by Gregory Corso (1954) (2016) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregory_Corso

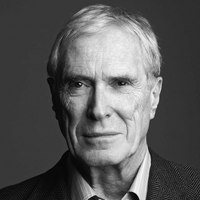

Robert Pinsky (born October 20, 1940) is an American poet, essayist, literary critic, and translator. From 1997 to 2000, he served as Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. Pinsky is the author of nineteen books, most of which are collections of his poetry. His published work also includes critically acclaimed translations, including The Inferno of Dante Alighieri and The Separate Notebooks by Czesław Miłosz. He teaches at Boston University. He received a B.A. from Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and earned both an M.A. and Ph.D. from Stanford University, where he was a Stegner Fellow in creative writing. He was a student of Francis Fergusson and Paul Fussell at Rutgers and Yvor Winters at Stanford.

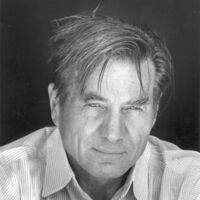

Anthony Evan Hecht (January 16, 1923– October 20, 2004) was an American poet. His work combined a deep interest in form with a passionate desire to confront the horrors of 20th century history, with the Second World War, in which he fought, and the Holocaust being recurrent themes in his work. Biography Early years Hecht was born in New York City to German-Jewish parents. He was educated at various schools in the city– he was a classmate of Jack Kerouac at Horace Mann School– but showed no great academic ability, something he would later refer to as “conspicuous.” However, as a freshman English student at Bard College in New York he discovered the works of Stevens, Auden, Eliot, and Dylan Thomas. It was at this point that he decided he would become a poet. Hecht’s parents were not happy at his plans and tried to discourage them, even getting family friend Ted Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, to attempt to dissuade him. In 1944, upon completing his final year at Bard, Hecht was drafted into the 97th Infantry Division and was sent to the battlefields in Europe. He saw combat in Germany in the “Ruhr Pocket” and in Cheb in Czechoslovakia. However, his most significant experience occurred on April 23, 1945 when Hecht’s division helped liberate Flossenbürg concentration camp. Hecht was ordered to interview French prisoners in the hope of gathering evidence on the camp’s commanders. Years later, Hecht said of this experience, The place, the suffering, the prisoners’ accounts were beyond comprehension. For years after I would wake shrieking. Career After the war ended, Hecht was sent to Japan, where he became a staff writer with Stars and Stripes. He returned to the US in March 1946 and immediately took advantage of the G.I. bill to study under the poet-critic John Crowe Ransom at Kenyon College, Ohio. Here he came into contact with fellow poets such as Randall Jarrell, Elizabeth Bishop, and Allen Tate. He later received his master’s degree from Columbia University. In 1947 Hecht attended the University of Iowa and taught in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, together with writer Robie Macauley, with whom Hecht had served during World War II, but, suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder after his war service, gave it up swiftly to enter psychoanalysis. Hecht released his first collection, A Summoning of Stones, in 1954. In this work his mastery of a wide range of poetic forms were clear as was his awareness of the forces of history, which he had seen first hand. Even at this stage Hecht’s poetry was often compared with that of Auden, with whom Hecht had become friends in 1951 during a holiday on the Italian island of Ischia, where Auden spent each summer. In 1993 Hecht published The Hidden Law, a critical reading of Auden’s body of work. During his career Hecht won many fans, and prizes, including the Rome Prize in 1951 and the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his second work The Hard Hours. It was within this volume that Hecht first addressed his own experiences of World War II - memories that had caused him to have a nervous breakdown in 1959. Hecht spent three months in hospital following his breakdown, although he was spared electric shock therapy, unlike Sylvia Plath, whom he had encountered while teaching at Smith College. Hecht’s main source of income was as a teacher of poetry, most notably at the University of Rochester, where he taught from 1967 to 1985. He also spent varying lengths of time teaching at other notable institutions such as Smith, Bard, Harvard, Georgetown, and Yale. Between 1982 and 1984, he held the esteemed position of Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. Hecht won a number of notable literary awards including: the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (for the volume The Hard Hours), the 1983 Bollingen Prize, the 1988 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the 1989 Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry, the 1997 Wallace Stevens Award, the 1999/2000 Frost Medal, and the Tanning Prize. Hecht died October 20, 2004, at his home in Washington, D. C.; he is buried at the cemetery at Bard College. One month later, on November 17, Hecht was awarded the National Medal of Arts, accepted on his behalf by his wife, Helen Hecht. The Anthony Hecht prize is awarded annually by the Waywiser press. Bibliography * Poetry * A Summoning of Stones (1954) * The Hard Hours (1967) * Millions of Strange Shadows (1977) * The Venetian Vespers (1979) * The Transparent Man (1990) * Flight Among the Tombs (1998) * The Darkness and the Light (2001) * Translations * Aeschylus’s Seven Against Thebes (1973) (with Helen Bacon) * Other Works * Obbligati: Essays in Criticism (1986) * The Hidden Law: The Poetry of W. H. Auden (1993) * On the Laws of the Poetic Art (1995) * Melodies Unheard: Essays on the Mysteries of Poetry (Johns Hopkins University Press) (2003) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Hecht

Born Asa Bundy Sheffey in 1913, Robert Hayden was raised in the poor neighborhood in Detroit called Paradise Valley. He had an emotionally tumultuous childhood and was shuttled between the home of his parents and that of a foster family, who lived next door. Because of impaired vision, he was unable to participate in sports, but was able to spend his time reading. In 1932, he graduated from high school and, with the help of a scholarship, attended Detroit City College (later Wayne State University). Hayden published his first book of poems, Heart-Shape in the Dust, in 1940, at the age of 27. He enrolled in a graduate English Literature program at the University of Michigan where he studied with W. H. Auden. Auden became an influential critical guide in the development of Hayden's writing. Hayden admired the work of Edna St. Vincent Millay, Elinor Wiley, Carl Sandburg, and Hart Crane, as well as the poets of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Jean Toomer. He had an interest in African-American history and explored his concerns about race in his writing. Hayden's poetry gained international recognition in the 1960s and he was awarded the grand prize for poetry at the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966 for his book Ballad of Remembrance. Explaining the trajectory of Hayden's career, the poet William Meredith wrote: "Hayden declared himself, at considerable cost in popularity, an American poet rather than a black poet, when for a time there was posited an unreconcilable difference between the two roles. There is scarcely a line of his which is not identifiable as an experience of black America, but he would not relinquish the title of American writer for any narrower identity." In 1975, Hayden received the Academy of American Poets Fellowship, and in 1976, he became the first black American to be appointed as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (later called the Poet Laureate). He died in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1980. References Poets.org - www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/196

Dorianne Laux (born January 10, 1952 in Augusta, Maine) is an American poet. Biography Laux worked as a sanatorium cook, a gas station manager, and a maid before receiving a B.A. in English from Mills College in 1988. Laux taught at the University of Oregon. She is a professor at North Carolina State University’s creative writing program, and the MFA in Writing Program at Pacific University. She is also a contributing editor at The Alaska Quarterly Review. Her work appeared in American Poetry Review, Five Points, Kenyon Review, Ms., Orion, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, Southern Review, TriQuarterly, Zyzzyva. She has also appeared in online journals such as Web Del Sol. Laux lives in Raleigh, North Carolina with her husband, poet Joseph Millar. She has one daughter.

Lorine Faith Niedecker (English: pronounced Needecker) (May 12, 1903 – December 31, 1970) was a Wisconsin poet and the only woman associated with the Objectivist poets. She is widely credited for demonstrating how an Objectivist poetic could handle the personal as subject matter. Niedecker was born on Black Hawk Island near Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin to Theresa (Daisy) Kunz and Henry Niedecker and lived most of her life in rural isolation. She grew up surrounded by the sights and sounds of the river until she moved to Fort Atkinson to attend school. This world of birds, trees, water and marsh was to inform her poetry for the rest of her life. On graduating from high school in 1922, she went to Beloit College to study literature but left after two years because her father was no longer able to pay her tuition. She devoted herself to caring for her ailing deaf mother, who was deeply depressed by her husband's flagrant affair with a neighbor woman. Niedecker married Frank Hartwig in 1928 but this relationship lasted only two years. Hartwig's fledgling road construction business foundered during the onset of the Great Depression while Lorine lost her job at the Fort Atkinson Library. The two separated in 1930 but were not legally divorced until 1942. Early writings Niedecker's earliest poetry was marked by her reading of the Imagists, whose work she greatly admired and of surrealism. In 1931, she read the Objectivist issue of Poetry. She was fascinated by what she saw and immediately wrote to Louis Zukofsky, who had edited the issue, sending him her latest poems. This was the beginning of what proved to be a most important relationship for her development as a poet. Zukofsky suggested sending them to Poetry, where they were accepted for publication. Suddenly, Niedecker found herself in direct contact with the American poetic avant-garde. Near the end of 1933, Niedecker visited Zukofsky in New York City for the first time and became pregnant with his child. He insisted that she have an abortion, which she did, although they remained friends and continued to carry on a mutually beneficial correspondence following Niedecker's return to Fort Atkinson. From the mid 1930s, Niedecker moved away from surrealism and started writing poems that engaged more directly with social and political realities and on her own immediate rural surroundings. Her first book, New Goose (1946), collected many of these poems. Neglect Niedecker was not to publish another book for fifteen years. In 1949, she began work on a poem sequence called For Paul, named for Zukofsky's son. Unfortunately, Zukofsky was uncomfortable with what he viewed as the overly personal and intrusive nature of the content of the 72 poems she eventually collected under this title and discouraged publication. Partly because of her geographical isolation, even magazine publication was not easily available and in 1955 she claimed that she had published work only six times in the previous ten years. Late flowering The 1960s saw a revival of interest in Niedecker's work. Wild Hawthorn Press and Fulcrum Press, both British-based, published books and magazine publication became regular. She was also befriended by a number of poets, including Cid Corman, Basil Bunting and several younger British and US poets who were interested in reclaiming the modernist heritage. Her books published in the last few decades of her life included My Friend Tree, T & G: The Collected Poems, 1936–1966, North Central, and My Life By Water. Encouraged by this interest, Niedecker started writing again. She had previously earned her living scrubbing hospital floors in Fort Atkinson, "reading proof" at a local magazine, renting cottages and living in near-poverty for years. However, her marriage in May 1963 to Albert Millen, an industrial painter at Ladish Drop Forge on Milwaukee's south side, brought financial stability back into her life. When Millen retired in 1968, the couple moved back to Blackhawk Island, taking up residence in a small cottage Lorine had built on property she inherited from her father. Niedecker died in 1970 from a cerebral hemorrhage, leaving behind several unpublished typescripts. Many other Niedecker papers were burned by Millen, who said he did so at Niedecker's request. Her name was added to her parents' headstone which uses the original spelling of the family name, Neidecker. Lorine had her name changed to the Niedecker spelling when she was in her twenties. The primary Niedecker archives are in the Dwight Foster Public Library (which inherited Niedecker's personal library) and the Hoard Museum in Fort Atkinson (which holds a collection of Niedecker's papers, as preserved and donated by her neighbor and close friend, Gail Roub). Niedecker's comprehensive Collected Works, edited by Jenny Penberthy, were published by the University of California Press in 2002. A centennial celebration of Niedecker's life and work, held in Milwaukee and Fort Atkinson in 2003, included treks to her two Rock River-edged homes on Black Hawk Island and symposium sessions including presentations by scholars and poets. Corman, Niedecker's literary executor who lived most of his creative life in Japan, made his last appearance in the United States during this event.

Edward Taylor (1642– June 29, 1729) was a colonial American poet, pastor and physician. Early life The son of a non-conformist yeoman farmer, Taylor was born in 1642 at Sketchley, Leicestershire, England. Following restoration of the monarchy and the Act of Uniformity under Charles II, which cost Taylor his teaching position, he immigrated in 1668 to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in America. Early days in America He chronicled his Atlantic crossing and early years in America (from April 26, 1668, to July 5, 1671) in his now-published Diary. He was admitted to Harvard College as a second year student soon after arriving in America and upon graduation in 1671 became pastor and physician at Westfield, on the remote western frontier of Massachusetts, where he remained until his death. Poetry Taylor’s poems, in leather bindings of his own manufacture, survived him, but he had left instructions that his heirs should “never publish any of his writings,” and the poems remained all but forgotten for more than 200 years. In 1937 Thomas H. Johnson discovered a 7,000-page quarto manuscript of Taylor’s poetry in the library of Yale University and published a selection from it in The New England Quarterly. The appearance of these poems, wrote Taylor’s biographer Norman S. Grabo, "established [Taylor] almost at once and without quibble as not only America’s finest colonial poet, but as one of the most striking writers in the whole range of American literature." His most important poems, the first sections of Preparatory Meditations (1682–1725) and God’s Determinations Touching His Elect and the Elects Combat in Their Conversion and Coming up to God in Christ: Together with the Comfortable Effects Thereof (c. 1680), were published shortly after their discovery. His complete poems, however, were not published until 1960. He is the only major American poet to have written in the metaphysical style. Taylor’s poems were an expression of his deeply held religious views, acquired during a strict upbringing and shaped in adulthood by New England Congregationalist Puritans, who developed during the 1630s and 1640s rules far more demanding than those of their co-religionists in England. Alarmed by a perceived lapse in piety, they concluded that professing belief and leading a scandal free life were insufficient for full participation in the local assembly. To become communing participants, “halfway members” were required to relate by testimony some personal experience of God’s saving grace leading to conversion, thus affirming that they were, in their own opinion and that of the church, assured of salvation. This requirement, expressed in the famous Halfway Covenant of 1662, was defended by such prominent churchmen as Increase and Cotton Mather and was readily embraced by Taylor, who became one of its most vocal advocates. Though not for the most part identifiably sectarian, Taylor’s poems nonetheless are marked by a robust spiritual content, characteristically conveyed by means of homely and vivid imagery derived from everyday Puritan surroundings. “Taylor transcended his frontier circumstances,” biographer Grabo observed, “not by leaving them behind, but by transforming them into intellectual, aesthetic, and spiritual universals.” Family He was twice married, first to Elizabeth Fitch, by whom he had eight children, five of whom died in childhood, and at her death to Ruth Wyllys, who bore six more children. Taylor himself died on June 29, 1729 in Westfield, Massachusetts. Works * “The Joy of Church Fellowship Rightly Attended” speaks of feelings of joyful acceptance as expressed in the singing of passengers riding in a coach on the way to heaven, accompanied by others, not yet members of the church, on foot. * In “Huswifery,” possibly his best known poem, Taylor speaks of the Christian (specifically puritanical) faith in terms of a spinning wheel and its various components, asking, in the first verse, * Make me, O Lord, thy spinning wheel complete. * Thy Holy Word my distaff make for me. * Make mine affections thy swift flyers neat * And make my soul thy holy spool to be. * My conversation make to be thy reel * And reel the yarn thereon spun of thy wheel. * “Meditation Eight” [even though this is a metaphysical poem] is centered on the concept of God’s being the living bread. * “The Preface to God’s Determination” [By personifying Calvanistic beliefs about life and death] speaks of the Creation, when God “filleted the earth so fine” and “in this Bowling Alley bowld the Sun.” * “Upon a Spider Catching a Fly” depicts Satan as a spider weaving a web to entangle man [and in doing so portrays the dance of death], who is saved by the mercy of God. Musical settings * The last stanza of Taylor’s 1685 poem Meditation. Isaiah 63.1. Glorious in his Appareil. was set as an anthem, My lovely one, from Three anthems, Op. 27, by English composer Gerald Finzi in 1946. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Taylor

Arthur Chapman (June 25, 1873– December 4, 1935) was an early twentieth-century American poet and newspaper columnist. He wrote a subgenre of American poetry known as Cowboy Poetry. His most famous poem was Out Where the West Begins. Out Where the West Begins Circa 1910, after reading in an Associated Press report of a conference of the governors of the western states at which the geographic beginning of the U.S. West was disputed, he hastily composed what was to become his most famous poem, “Out Where the West Begins,” celebrating the people and the land of the frontier. The first of its three seven-line stanzas ran "Out where the handclasp’s a little stronger, / Out where the smile dwells a little longer, / That’s where the West begins; / Out where the sun is a little brighter, / Where the snows that fall are a trifle whiter, / Where the bonds of home are a wee bit tighter, / That’s where the West begins." The poem was an immediate sensation, widely quoted, often imitated, and more often parodied. (One popular anonymous take-off read, in part, "Where the women boss and the men folk think / That toast is food and tea is a drink; / Where the men use powder and the wrist watch ticks, / And everyone else but themselves are hicks / That’s where the East begins.") According to the dust jacket of Chapman’s 1921 novel, Mystery Ranch, "To-day ["Out Where the West Begins"] is perhaps the best-known bit of verse in America. It hangs framed in the office of the Secretary of the Interior at Washington. It has been quoted in Congress, and printed as campaign material for at least two Governors. . . . [Chapman’s poems possess] a rich Western humor such as had not been heard in American poetry since the passing of Bret Harte.” The popularity of “Out Where the West Begins” led Chapman to arrange for its publication in book form, and in 1916 he produced Out Where the West Begins, and Other Small Songs of a Big Country, a modest fifteen-page volume issued by Carson-Harper in Denver. It was an immediate success and Houghton Mifflin of Boston and New York immediately offered to publish a larger collection. Out Where the West Begins, and Other Western Verses, as it was renamed, appeared in 1917 with fifty-eight poems on ninety-two pages. The title poem was widely reprinted on postcards and plaques. It was frequently set to music, first in 1920, and achieved a separate life on the concert stage. Chapman followed the popular volume in 1921 with the equally successful Cactus Center: Poems of an Arizona Town, containing thirty poems and running to 123 pages. The Literary Review wrote of the verse, "In vigor of style, [it] irresistibly suggests a transplanted Kipling" (19 Feb. 1921, p. 12). The Move East In 1919 Chapman moved to New York City, where he lived in a fashionable neighborhood on the east side of Manhattan and took a job as a staff writer for the Sunday edition of the New York Tribune. He held that position until his retirement in 1925, the year after the newspaper became the New York Herald Tribune. After his wife died in 1923 Chapman married Kathleen Caesar, an editor of the Bell Syndicate; no children were born of his second marriage. He wrote fiction and nonfiction throughout his career as a journalist and continued after he retired. His first effort at book-length fiction, Mystery Ranch (1921), combined the genres of western adventure and murder mystery. The Literary Review dismissed it as “melodramatic” and stated that it provided “little for the seeker of literary values” (19 Nov. 1921, p. 190), but the New York Times more charitably credited Chapman, “known heretofore as a poet of the West,” with being “a clever technician in a new field” (13 Nov. 1921). The book had modest commercial success, but Chapman’s second novel, John Crews (1926), an equally stereotypical adventure-romance of frontier life, sold better. Described by the New York Herald Tribune as “a lively and continuously readable yarn,” it was successful enough to have a reprint edition by another publisher in its first year (28 Mar. 1926). In 1924 Chapman capitalized on his reputation as an expert on the U.S. West with the publication of The Story of Colorado, Out Where the West Begins, a richly illustrated history of the state. His final book was an extensively researched and detailed volume, The Pony Express: The Record of a Romantic Adventure in Business (1932), complete with bibliography, index, and maps. Both were well received by the critics and the public. It was, however, for his poetry that Chapman became and remained famous. His western dialect poems and “Out Where the West Begins” continued to be quoted and to appear in anthologies long after his death, and both of his volumes of verse were brought out in new editions by other publishers as late as 2010. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Chapman_(poet)

Robert Francis (August 12, 1901; Upland, Pennsylvania– July 13, 1987) was an American poet who lived most of his life in Amherst, Massachusetts. Life Robert Francis was born on August 12, 1901 in Upland, Pennsylvania. He graduated from Harvard University in 1923. He would later attend the Graduate School of Education at Harvard where he once said that he felt that he’d come home. He lived in a small house he built himself in 1940, which he called Fort Juniper, near Cushman Village in Amherst, Massachusetts. One of his poetic mentors was Robert Frost, and indeed Francis’s first volume of poems, Stand Here With Me (1936), displays a poetic voice eerily reminiscent of Frost’s own in carefully crafted nature poems. Frost once said: “poetry is the only acceptable way to say one thing and mean another.” Later work Francis published very little during the 1940s–1950s. He decided that “for better or worse, I was a poet and there was really nothing else for me to do but go on being a poet. It was too late to change even if I had wanted to. Poetry was my most central, intense and inwardly rewarding experience.” In 1960, Francis published The Orb Weaver, which revived his reputation as a poet. Francis uses hidden meanings in his poems, which suggest another way that Frost made an impression on Francis’s poetry. In later volumes, Francis found a voice distinctively his own, relaxed in meter and characterized by puns, word-plays, slant rhymes, and repetitions of key words. Aside from one long narrative poem in Frostian blank verse, Francis’s poetry consists largely of concise lyrics, somewhat limited in thematic range but intensely crafted and deeply personal. Frost would later say that Robert Francis was America’s best neglected poet. He often wrote about nature and baseball. His autobiography, The Trouble with Francis, was published in 1971 and details his struggle with neglect. Francis died July 13, 1987. Awards * Francis won the Shelley Memorial Award in 1939. In 1984 the Academy of American Poets gave Francis its award for distinguished poetic achievement. Works Poetry * * Stand Here With Me. The Macmillan Company. 1936. * The Face Against the Glass. by the author. 1950. * The Orb Weaver. University Press of New England. 1960. ISBN 978-0-8195-1005-1. * Come out into the sun: poems new and selected. University of Massachusetts Press. 1965. ISBN 978-0-87023-015-8. * Like ghosts of eagles: poems, 1966–1974. University of Massachusetts Press. 1974. * Collected Poems, 1936–1976. NetLibrary, Incorporated. 1985. ISBN 978-0-585-28147-6. * Late fire, late snow: new and uncollected poems. University of Massachusetts Press. 1992. ISBN 978-0-87023-814-7. * http://www.poemhunter.com/best-poems/robert-francis/thoreau-in-italy/ Autobiography * The Trouble with Francis. University of Massachusetts Press. 1971. ISBN 978-0-87023-083-7. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Francis_(poet)

Donald Justice was an American poet and teacher of writing. In summing up Justice's career David Orr wrote, "In most ways, Justice was no different from any number of solid, quiet older writers devoted to traditional short poems. But he was different in one important sense: sometimes his poems weren't just good; they were great. They were great in the way that Elizabeth Bishop's poems were great, or Thom Gunn's or Philip Larkin's. They were great in the way that tells us what poetry used to be, and is, and will be." Justice grew up in Florida and earned a bachelor's degree from the University of Miami in 1945. He received an M.A. from the University of North Carolina in 1947, studied for a time at Stanford University, and ultimately earned a doctorate from the University of Iowa in 1954. He went on to teach for many years at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, the nation's first graduate program in creative writing. He also taught at Syracuse University, the University of California at Irvine, Princeton University, the University of Virginia, and the University of Florida in Gainesville. Justice published thirteen collections of his poetry. The first collection, The Summer Anniversaries, was the winner of the Lamont Poetry Prize given by the Academy of American Poets in 1961; Selected Poems won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1980. He was awarded the Bollingen Prize in Poetry in 1991, and the Lannan Literary Award for Poetry in 1996. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets from 1997 to 2003. His Collected Poems was nominated for the National Book Award in 2004. Justice was also a National Book Award Finalist in 1961, 1974, and 1995. In his obituary, Andrew Rosenheim notes that Justice "was a legendary teacher, and despite his own Formalist reputation influenced a wide range of younger writers — his students included Mark Strand, Rita Dove, James Tate, Jorie Graham and the novelist John Irving". His student and later colleague Marvin Bell said in a reminiscence, "As a teacher, Don chose always to be on the side of the poem, defending it from half-baked attacks by students anxious to defend their own turf. While he had firm preferences in private, as a teacher Don defended all turfs. He had little use for poetic theory..." Of Justice's accomplishments as a poet, his former student, the poet and critic Tad Richards, noted that "Donald Justice is likely to be remembered as a poet who gave his age a quiet but compelling insight into loss and distance, and who set a standard for craftsmanship, attention to detail, and subtleties of rhythm." Justice's work was the subject of the 1998 volume Certain Solitudes: On The Poetry of Donald Justice, a collection of essays edited by Dana Gioia and William Logan. Poetry * The Old Bachelor and Other Poems (Pandanus Press, Miami, FL), 1951. * The Summer Anniversaries (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT), 1960; revised edition (University Press of New England, Hanover, NH), 1981. * A Local Storm (Stone Wall Press, Iowa City, IA, 1963). * Night Light (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT, 1967); revised edition (University Press of New England, Hanover, NH, 1981). * Sixteen Poems (Stone Wall Press, Iowa City, IA, 1970). * From a Notebook (Seamark Press, Iowa City, IA, 1971). * Departures (Atheneum, New York, NY, 1973). * Selected Poems (Atheneum, New York, NY, 1979). * Tremayne (Windhover Press, Iowa City, IA, 1984). * The Sunset Maker (Anvil Press Poetry, 1987). * A Donald Justice Reader (Middlebury, 1991). * New and Selected Poems (Knopf, 1995). * Orpheus Hesitated beside the Black River: Poems, 1952-1997 (Anvil Press Poetry, London, England), 1998. * Collected Poems (Knopf, 2004). Essay and interview collections * Oblivion: On Writers and Writing, 1998 * Platonic Scripts, 1984 References Wikipedia—http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Justice

Larry Patrick Levis (September 30, 1946– May 8, 1996) was an American poet. Youth and education Larry Levis was born the son of a grape grower; he grew up driving a tractor, picking grapes, and pruning vines of Selma, California, a small fruit-growing town in the San Joaquin Valley. He later wrote of the farm, the vineyards, and the Mexican migrant workers that he worked alongside. He also remembered hanging out in the local billiards parlor on Selma’s East Front Street, across from the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks. Levis earned a bachelor’s degree from Fresno State College in 1968, a master’s degree from Syracuse University in 1970, and a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa in 1974. Awards and recognition Levis won the United States Award from the International Poetry Forum for his first book of poems, Wrecking Crew (1972), which included publication by the University of Pittsburgh Press. The Academy of American Poets named his second book, The Afterlife (1976) as Lamont Poetry Selection. His book The Dollmaker’s Ghost was a winner of the Open Competition of the National Poetry Series. Other awards included a YM-YWHA Discovery award, three fellowships in poetry from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Fulbright Fellowship, and a 1982 Guggenheim Fellowship. His poems are featured in American Alphabets: 25 Contemporary Poets (2006) and in many other anthologies. Larry Levis died of a heart attack in Richmond, Virginia on May 8, 1996, at the age of 49. Academic career Levis taught English at the University of Missouri from 1974–1980. From 1980 to 1992, he taught at the creative writing program at the University of Utah. He was co-editor of Missouri Review, from 1977 to 1980. He also taught at the Warren Wilson College MFA Program for Writers. From 1992 until his death from a heart attack in 1996 he was a professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University, which annually awards the Levis Reading Prize in his remembrance (articles about Levis and the prize are featured each year in Blackbird, an online journal of literature and the arts). Selected bibliography * Poetry * Wrecking Crew (1972) * The Afterlife (1977) * The Dollmaker’s Ghost (1981) * Winter Stars (1985) * The Widening Spell of the Leaves (1991) * Elegy (1997) * The Selected Levis (2000) * Prose * The Gazer Within (2000) * Fiction * Black Freckles (1992) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larry_Levis

Genevieve Taggard (November 28, 1894 Waitsburg, Washington– November 8, 1948 New York City) was an American poet. During the 1930s, sparked in part by the Great Depression, but also largely by her philanthropic upbringing and her commitment to socialism, her poetry began to reflect her political and social views much more prominently. During this time a Guggenheim Fellowship allowed her to spend a year in Majorca, Spain and Antibes, France. The experience of Spain in its time shortly before the Spanish Civil War gave further rise and inspiration to her cause of raising social and political awareness of civil rights issues.

Edward Hirsch (born January 20, 1950) is an American poet and critic who wrote a national bestseller about reading poetry. He has published nine books of poems, including The Living Fire: New and Selected Poems (2010), which brings together thirty-five years of work, and Gabriel: A Poem (2014), a book-length elegy for his son that The New Yorker calls “a masterpiece of sorrow.” He has also published five prose books about poetry. He is president of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in New York City (not to be mistaken with E.D. Hirsch, Jr.). Life Hirsch was born in Chicago. He had a childhood involvement with poetry, which he later explored at Grinnell College and the University of Pennsylvania, where he received a Ph.D. in folklore. Hirsch was a professor of English at Wayne State University. In 1985, he joined the faculty at the University of Houston, where he spent 17 years as a professor in the Creative Writing Program and Department of English. He was appointed the fourth president of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation on September 3, 2002. He holds seven honorary degrees. Career Hirsch is a well-known advocate for poetry whose essays have been published in the American Poetry Review, The New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, and elsewhere. He wrote a weekly column on poetry for The Washington Post Book World from 2002-2005, which resulted in his book Poet’s Choice (2006). His other prose books include Responsive Reading (1999), The Demon and the Angel: Searching for the Source of Artistic Inspiration (2002), and A Poet’s Glossary (2014), a complete compendium of poetic terms. He is the editor of Transforming Vision: Writers on Art (1994), Theodore Roethke’s Selected Poems (2005) and To a Nightingale (2007). He is the co-editor of A William Maxwell Portrait: Memories and Appreciations and The Making of a Sonnet: A Norton Anthology (2008). He also edits the series “The Writer’s World” (Trinity University Press). Hirsch’s first collection of poems, For the Sleepwalkers, received the Lavan Younger Poets Award from the Academy of American Poets and the Delmore Schwartz Memorial Award from New York University. His second book, Wild Gratitude, received the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1986. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1985 and a five-year MacArthur Fellowship in 1997. He received the William Riley Parker Prize from the Modern Language Association for the best scholarly essay in PMLA for the year 1991. He has also received an Ingram Merrill Foundation Award, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome, a Pablo Neruda Presidential Medal of Honor, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award for Literature. He is a former Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Hirsch’s book, How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry (1999), was a surprise bestseller and is widely taught throughout the country. Works Poetry collections * For the Sleepwalkers, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981) * Wild Gratitude, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986) * The Night Parade, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989) * Earthly Measures, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994) ISBN 0-679-76566-2 * On Love, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998) * Lay Back the Darkness (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003) ISBN 0-375-41521-1 * Special Orders (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008) ISBN 0-307-26681-8 * Gabriel A Poem (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014) ISBN 978-0-385-35357-1 Non-fiction books * Transforming Vision: Writers on Art, Selected and Introduced by Edward Hirsch, (Boston: Little, Brown, 1994) ISBN 0-8212-2126-4 * How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry, (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999) ISBN 0-15-100419-6 * Responsive Reading, (1999) * 'Introduction’ in John Keats, Complete Poems and Selected Letters of John Keats, (New York: Modern Library, 2001) ISBN 0-375-75669-8 * The Demon and the Angel: Searching for the Source of Artistic Expression, (New York: Harcourt Brace, 2002) * Poet’s Choice, (New York: Harcourt, 2006) ISBN 0-15-101356-X * A Poet’s Glossary, (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014) ISBN 978-0-15-101195-7 Editor * Transforming Vision: Writers on Art, (The Art Institute of Chicago/ Bulfinch Press, 1994) ISBN 978-0821221266 * A William Maxwell Portrait, (Norton, 2004) ISBN 978-0393057713 * Theodore Roethke: Selected Poems, (The Library of America, 2005) ISBN 978-1931082785 * Irish Writers on Writing, edited with Eavan Boland, (Trinity University Press, 2007) ISBN 9781595340320 * Polish Writers on Writing, edited with Adam Zagajewski, (Trinity University Press, 2007) ISBN 9781595340337 * To a Nightingale: Poems from Sappho to Borges, (Braziller, 2007) ISBN 978-0807616277 * The Making of a Sonnet, (Norton, 2008) ISBN 978-0393333534 * Hebrew Writers on Writing, edited with Peter Cole (Trinity University Press, 2008) ISBN 9781595340528 * Nineteenth-Century American Writers on Writing, edited with Brenda Wineapple (Trinity University Press, 2010) ISBN 9781595340696 * Chinese Writers on Writing, edited with Arthur Sze (Trinity University Press, 2010) ISBN 9781595340634 * Romanian Writers on Writing, edited with Norman Manea, (Trinity University Press, 2011) ISBN 9781595340825 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Hirsch

Robert Edward Duncan (January 7, 1919 in Oakland, California– February 3, 1988) was an American poet and a devotee of H.D. and the Western esoteric tradition who spent most of his career in and around San Francisco. Though associated with any number of literary traditions and schools, Duncan is often identified with the poets of the New American Poetry and Black Mountain College. Duncan saw his work as emerging especially from the tradition of Pound, Williams and Lawrence. Duncan was a key figure in the San Francisco Renaissance.