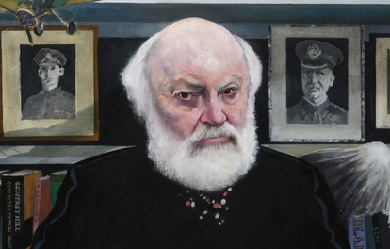

Basil Cheesman Bunting (1 March 1900– 17 April 1985) was a significant British modernist poet whose reputation was established with the publication of Briggflatts in 1966. He had a lifelong interest in music that led him to emphasise the sonic qualities of poetry, particularly the importance of reading poetry aloud. He was an accomplished reader of his own work. Life and career Born into a Quaker family in Scotswood-on-Tyne, Northumberland, he studied at two Quaker schools: from 1912 to 1916 at Ackworth School in the West Riding of Yorkshire and from 1916 to 1918 at Leighton Park School in Berkshire. His Quaker education strongly influenced his pacifist opposition to the First World War, and in 1918 he was arrested as a conscientious objector having been refused recognition by the tribunals and refusing to comply with a notice of call-up. Handed over to the military, he was court-martialled for refusing to obey orders, and served a sentence of more than a year in Wormwood Scrubs and Winchester prisons. Bunting’s friend Louis Zukofsky described him as a "conservative/anti-fascist/imperialist", though Bunting himself listed the major influences on his artistic and personal outlook somewhat differently as “Jails and the sea, Quaker mysticism and socialist politics, a lasting unlucky passion, the slums of Lambeth and Hoxton ...” These events were to have an important role in his first major poem, “Villon” (1925). “Villon” was one of a rather rare set of complex structured poems that Bunting labelled “sonatas,” thus underlining the sonic qualities of his verse and recalling his love of music. Other “sonatas” include “Attis: or, Something Missing,” “Aus Dem Zweiten Reich,” “The Well of Lycopolis,” “The Spoils” and, finally, “Briggflatts.” After his release from prison in 1919, traumatised by the time spent there, Bunting went to London, where he enrolled in the London School of Economics, and had his first contacts with journalists, social activists and Bohemia. Bunting was introduced to the works of Ezra Pound by Nina Hamnett who lent him a copy of Homage to Sextus Propertius. The glamour of the cosmopolitan modernist examples of Nina Hamnett and Mina Loy seems to have influenced Bunting in his later move from London to Paris. After travelling in Northern Europe, Bunting left the London School of Economics without a degree and went to France. There, in 1923, he became friendly with Ezra Pound, who years later would dedicate his Guide to Kulchur (1938) to both Bunting and Louis Zukofsky, “strugglers in the desert”. Between February and October 1927, Bunting wrote articles and reviews for The Outlook, and then became its music critic until the magazine ceased publication in 1928. Bunting’s poetry began to show the influence of the friendship with Pound, whom he visited in Rapallo, Italy, and later settled there with his family from 1931 to 1933. He was published in the Objectivist issue of Poetry magazine, in the Objectivist Anthology, and in Pound’s Active Anthology. During the Second World War, Bunting served in British Military Intelligence in Persia. After the war, in 1948, he left government service to become the correspondent for The Times of London, in Iran. He married an Iranian woman– Sima Alladian– whilst continuing his intelligence work with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company Tehran, until he was expelled by Mohammad Mossadegh in 1952. Back in Newcastle, he worked as a journalist on the Evening Chronicle until his rediscovery during the 1960s by young poets, notably Tom Pickard and Jonathan Williams, who were interested in working in the modernist tradition. In 1965, he published his major long poem, Briggflatts, named after the Quaker village in Cumbria where he is now buried. In later life he published Advice to Young Poets, beginning "I SUGGEST / 1. Compose aloud; poetry is a sound.” Bunting died in 1985 in Hexham, Northumberland. The Basil Bunting Poetry Award and Young Person’s Prize, administered by Newcastle University, are open internationally to any poet writing in English. Briggflatts Divided into five parts, Briggflatts is an autobiographical long poem, looking back on teenage love and on Bunting’s involvement in the high modernist period. In addition, Briggflatts can be read as a meditation on the limits of life and a celebration of Northumbrian culture and dialect, as symbolised by events and figures like the doomed Viking King Eric Bloodaxe. The critic Cyril Connolly was among the first to recognise the poem’s value, describing it as “the finest long poem to have been published in England since T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets”. Portrait bust of Basil Bunting Basil Bunting sat in Northumberland for sculptor Alan Thornhill, with a resulting terracotta (for bronze) in existence. The correspondence file relating to the Bunting portrait bust is held as part of the Thornhill Papers (2006:56) in the archive of the Henry Moore Foundation’s Henry Moore Institute in Leeds and the terracotta remains in the collection of the artist. The 1973 portrait is displayed in the Burton (2014) biography of Bunting. In popular culture Mark Knopfler wrote a song, titled 'Basil’, about his time as a Saturday afternoon copy boy on the Newcastle Evening Chronicle when Bunting worked there. The song was recorded for Knopfler’s 2015 album Tracker. Books * 1930: Redimiculum Matellarum (privately printed) * 1950: Poems (Cleaners’ Press, 1950) revised and published as Loquitur (Fulcrum Press, 1965). * 1951: The Spoils * 1965: First Book of Odes * 1965: Ode II/2 * 1966: Briggflatts: An Autobiography * 1967: Two Poems * 1967: What the Chairman Told Tom * 1968: Collected Poems * 1972: Version of Horace * 1991: Uncollected Poems (posthumous, edited by Richard Caddel) * 1994: The Complete Poems (posthumous, edited by Richard Caddel) * 1999: Basil Bunting on Poetry (posthumous, edited by Peter Makin) * 2000: Complete Poems (posthumous, edited by Richard Caddel) * 2009: Briggflatts (with audio CD and video DVD) * 2012: Bunting’s Persia (Translations by Basil Bunting. Edited by Don Share) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basil_Bunting

James Laughlin (October 30, 1914 – November 12, 1997) was an American poet and literary book publisher who founded New Directions Publishing. He was born in Pittsburgh, the son of Henry Hughart and Marjory Rea Laughlin. Laughlin's family had made its fortune with the Jones and Laughlin Steel Company, founded three generations earlier by his great grandfather, James H. Laughlin, and this wealth would partially fund Laughlin's future endeavors in publishing. As Laughlin once wrote, "none of this would have been possible without the industry of my ancestors, the canny Irishmen who immigrated in 1824 from County Down to Pittsburgh, where they built up what became the fourth largest steel company in the country. I bless them with every breath." Laughlin's boyhood home is now part of the campus of Chatham University. At The Choate School (now Choate Rosemary Hall) in Wallingford, Connecticut, Laughlin showed an early interest in literature. An important influence on Laughlin at the time was the Choate teacher and translator Dudley Fitts, who later provided Laughlin with introductions to prominent writers such as Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound. Harvard University, where Laughlin matriculated in 1933, had a more conservative literary bent, embodied in the poet and professor Robert Hillyer, who directed the writing program. According to Laughlin, Hillyer would leave the room when either Pound or Eliot was mentioned. In 1934, Laughlin traveled to France, where he met Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. Laughlin accompanied the two on a motoring tour of southern France and wrote press releases for Stein's upcoming visit to the U.S. He proceeded to Italy to meet and study with Ezra Pound, who famously told him, "You're never going to be any good as a poet. Why don't you take up something useful?" Pound suggested publishing. Later, Laughlin took a leave of absence from Harvard and stayed with Pound in Rapallo for several months. When Laughlin returned to Harvard, he used money from his father to found New Directions, which he ran first from his dorm room and later from a barn on his Aunt Leila Laughlin Carlisle's estate in Norfolk, Connecticut. (The firm opened offices in New York soon after, first at 333 Sixth Avenue and later at 80 Eighth Avenue, where it remains today.) With funds from his graduation gift, Laughlin endowed New Directions with more money, ensuring that the company could stay afloat even though it did not turn a profit until 1946. The first publication of the new press, in 1936, was New Directions in Prose & Poetry, an anthology of poetry and writings by authors such as William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, Elizabeth Bishop, Henry Miller, Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, and E. E. Cummings, a roster that heralded the fledgling company's future as a preeminent publisher of modernist literature. The volume also included a poem by "Tasilo Ribischka," a pseudonym for Laughlin himself. New Directions in Prose and Poetry became an annual publication, issuing its final number in 1991. Within just a few years New Directions had become an important publisher of modernist literature. Initially, it emphasized contemporary American writers with whom Laughlin had personal connections, such as William Carlos Williams and Pound. A born cosmopolitan, though, Laughlin also sought out cutting-edge European and Latin American authors and introduced their work to the American market. One important example of this was Hermann Hesse's novel Siddhartha, which New Directions initially published in 1951. Laughlin often remarked that the popularity of Siddhartha subsidized the publication of many other money-losing books of greater importance. Although of draft age, Laughlin avoided service in World War II due to a 4-F classification. Laughlin, like several of his male ancestors and like his son Robert, suffered from depression. Robert committed suicide in 1986 by stabbing himself multiple times in the bathtub. Laughlin later wrote a poem about this, called Experience of Blood, in which he expresses his shock at the amount of blood in the human body. Despite the horrific mess left as a result, Laughlin reasons that he cannot ask anyone else to clean it up, "because after all, it was my blood too." A natural athlete and an avid skier, Laughlin traveled the world skiing and hiking. With money from his graduation gift, he founded the Alta Ski Area in Utah and was part-owner of the resort there for many years. Laughlin also spearheaded the surveying of the Albion-Sugarloaf ski area, along with Alta notables Chic Morton, Alf Engen, and fellow Ski Enthusiast and Painter Ruth Rogers-Altmann. At times Laughlin's skiing got in the way of his business. After publishing William Carlos Williams' novel White Mule in 1937, Laughlin left for an extended ski trip. When reviewers sought additional copies of the novel, Laughlin was not available to give the book the push it could have used, and as a result Williams nursed a grudge against the young publisher for years. Laughlin's outdoor activities helped other literary friendships, though; for many years he and Kenneth Rexroth took an annual camping trip together in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California. In the 1960s, Laughlin published Rexroth's friend, the poet and essayist Gary Snyder, also an avid outdoorsman. In the early 1950s, Laughlin took part in what has come to be known as the Cultural Cold War against the Soviet Union. With funding from the Ford Foundation and with the assistance of poet and editor Hayden Carruth, Laughlin founded a nonprofit called "Intercultural Publications" that sought to publish a quarterly journal of American arts and letters, PERSPECTIVES USA, in Europe. Sixteen issues of the journal eventually appeared. Although Laughlin wished to continue the journal, the Ford Foundation cut off funding, asserting that PERSPECTIVES had limited impact and that its money would be better spent on the more effective Congress for Cultural Freedom. Following the dissolution of Intercultural Publications, Laughlin became deeply involved in the activities of the Asia Society. Pound's advice to Laughlin to give up poetry didn't stick. He published his first book of poetry, SOME NATURAL THINGS, in 1945, and continued to write verse until his death. Although he never enjoyed the acclaim that the writers he published received, Laughlin's verse (which is plainspoken and focused on everyday experience, reminiscent of Williams or even the Roman poet Catullus) was well-respected by other poets, and in the 1990s the NEW YORKER published six of his poems. Among his books are IN ANOTHER COUNTRY, THE COUNTRY ROAD, and the posthumous autobiographical poem BYWAYS. Laughlin won the 1992 Distinguished Contribution to American Letters Award from the National Book Awards Program. The Academy of American Poets' James Laughlin award, for a poet's second book, is named in his honor. He died of complications related to a stroke in Norfolk, Connecticut, at age 83. Works Laughlin's works include: * In Another Country (1979) * Selected Poems (1986) * The House of Light (1986) * Tabellae (1986) * The Owl of Minerva (Copper Canyon Press, 1987) * Collemata and Pound As Wuz (1988) * The Bird of Endless Time (Copper Canyon Press, 1989) * Collected Poems of James Laughlin (1992) * Angelica (1992) * The Man in the Wall (1993) * The Country Road (1995) * The Secret Room (1997) * A Commonplace Book of Pentastichs (1998) * Byways: A Memoir (2005) * The Way It Wasn't: From the Files of James Laughlin (2006) * Laughlin's correspondence with William Carlos Williams, Henry Miller, Thomas Merton, Delmore Schwartz, Ezra Pound, and others has been published in a series of volumes issued by Norton. References Wikipedia—http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Laughlin

Reginald Gibbons (born 1947) is an American poet, fiction writer, translator, literary critic, and Professor of English and Classics at Northwestern University and Director of the Center for the Writing Arts there. Gibbons has published numerous books, as well as poems, short stories, essays and reviews in journals and magazines, has held Guggenheim Foundation and NEA fellowships in poetry and a research fellowship from the Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington D.C. He has won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, the Carl Sandburg Prize, the Folger Shakespeare Library’s O. B. Hardison, Jr. Poetry Prize, and other honors, among them the inclusion of his work in Best American Poetry and Pushcart Prize anthologies. His book Creatures of a Day was a finalist for the 2008 National Book Award for poetry. He attended public school in Spring Branch (at that time, outside Houston, Texas; now incorporated into the city), Princeton University (BA Spanish and Portuguese), and Stanford University (MA in English and Creative Writing; PhD in Comparative Literature). Before moving to Northwestern University, he taught creative writing at Princeton and Columbia. At Northwestern, he was the editor of TriQuarterly magazine from 1981 to 1997, and co-founded TriQuarterly Books (after 1997, an imprint of Northwestern University Press). As the editor of TriQuarterly, he edited or co-edited the special issues Chicago (1984), From South Africa: New Writing, Photography and Art (1987), A Window on Poland (1983), Prose from Spain (1983), New Writing from Mexico (1992), and others, as well as many general issues of the magazine. He edited two works of William Goyen (1915-1983): the 50th Anniversary edition of The House of Breath and the Goyen’s posthumously published second novel, Half a Look of Cain (both published by Northwestern University Press). In 1989, he was one of a group of co-founders of the Guild Literary Complex (Chicago), a literary presenting organization, where he continues to volunteer, and he is a member of the large team that is creating the American Writers Museum (Chicago; opening in 2017). Career * Lecturer in creative writing, Princeton University (Princeton, NJ), 1976-1980 * Lecturer in creative writing, Columbia University School of General Studies, 1980-81 * Professor of English, Northwestern University (Evanston, IL), 1981- * Editor of TriQuarterly magazine, 1981-1997 * Core faculty member of MFA Program for Writers, Warren Wilson College (Asheville, NC), 1989-2011 * Co-founder and member of the board of directors, Guild Complex, 1989- * Member, National Advisory Council and Content Leadership Team, American Writers Museum, 2012- Poetry * Roofs Voices Roads. (Quarterly Review of Literature, 1979). * The Ruined Motel. (Houghton, 1981). * Saints. (Persea Books, 1986). * Maybe It Was So. (University of Chicago Press, 1991). ISBN 978-0-226-29056-0 * Sparrow: New and Selected Poems. (LSU Press, 1997). ISBN 978-0-8071-2232-7 * Homage to Longshot O’Leary: Poems. (Holy Cow! Press, 1999). * It’s Time: Poems. (LSU Press, 2002). ISBN 978-0-8071-2815-2 * Creatures of a Day: Poems. (LSU Press, 2008). ISBN 978-0-8071-3318-7 * Desde una barca de papel (Poemas 1981-2008). (Littera Libros (Villanueva de la Serena, SPAIN), 2009. (Bilingual edition) * Slow Trains Overhead: Chicago Poems and Stories. (University of Chicago Press, 2010). ISBN 978-0-226-29058-4 * L’abitino blue. (Gattomerlino (Rome, ITALY). (Bilingual edition) * Last Lake. (University of Chicago Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0-226-41745-5 Fiction * Sweetbitter: A Novel. (LSU Press, 2003). ISBN 978-0-8071-2871-8 * Five Pears or Peaches. (Broken Moon Press, 1991). * Orchard in the Street. (BOA Editions, Ltd, forthcoming 2017). Other Books * Sophocles, Selected Poems: Odes and Fragments (Princeton University Press, 2008.) Translated and Introduced by Reginald Gibbons. ISBN 978-0-691-13024-8 * How Poems Think (University of Chicago Press, 2015). ISBN 978-0-226-27800-1 * Sophocles, Antigone (Oxford University Press, 2007). Translated by Reginald Gibbons and Charles Segal. ISBN 978-0-19514310-2 * Goyen: Autobiographical Essays, Notesbooks, Evocations, Interviews, by William Goyen (University of Texas Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-292-72225-5 * The Complete Sophocles, Volume I: The Theban Plays (Oxford University Press, 2011.) Antigone translated by Reginald Gibbons and Charles Segal. ISBN 978-0-19-538880-0 * The Complete Euripides, Volume IV: Bacchae and Other Plays (Oxford University Press, 2009.) Bacchae translated by Reginald Gibbons and Charles Segal. ISBN 978-0-19-537340-0 * New Writing from Mexico, edited by Reginald Gibbons. TriQuarterly Books, 1992. * Thomas McGrath: Life and the Poem, edited by Reginald Gibbons and Terrence Des Press. (University of Illinois Press, 1992. ISBN 0-252-06177-2 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reginald_Gibbons

Jean Ingelow (17 March 1820– 20 July 1897), was an English poet and novelist. She also wrote several stories for children. Early life Born at Boston, Lincolnshire, she was the daughter of William Ingelow, a banker. As a girl she contributed verses and tales to magazines under the pseudonym of Orris, but her first (anonymous) volume, A Rhyming Chronicle of Incidents and Feelings, which came from an established London publisher, did not appear until her thirtieth year. This was called charming by Tennyson, who declared he should like to know the author; they later became friends. Professional life Jean Ingelow followed this book of verse in 1851 with a story, Allerton and Dreux, but it was the publication of her Poems in 1863 which suddenly made her a popular writer. This ran rapidly through numerous editions and was set to music, proving very popular for English domestic entertainment. Her work often focused on religious introspection. In the United States, her poems obtained great public acclaim, and the collection was said to have sold 200,000 copies. In 1867 she edited, with Dora Greenwell, The Story of Doom and other Poems, a collection of poetry for children At that point Ingelow gave up verse for a while and became industrious as a novelist. Off the Skelligs appeared in 1872, Fated to be Free in 1873, Sarah de Berenger in 1880, and John Jerome in 1886. She also wrote Studies for Stories (1864), Stories told to a Child (1865), Mopsa the Fairy (1869), and other stories for children. Ingelow’s children’s stories were influenced by Lewis Carroll and George MacDonald. Mopsa the Fairy, about a boy who discovers a nest of fairies and discovers a fairyland while riding on the back of an albatross) was one of her most popular works (it was reprinted in 1927 with illustrations by Dorothy P. Lathrop). Anne Thaxter Eaton, writing in A Critical History of Children’s Literature, calls the book “a well-constructed tale”, with “charm and a kind of logical make-believe.” Her third series of Poems was published in 1885. Jean Ingelow’s last years were spent in Kensington, by which time she had outlived her popularity as a poet. She died in 1897 and was buried in Brompton Cemetery, London. Criticism Ingelow’s poems, collected in one volume in 1898, were frequently popular successes. “Sailing beyond Seas” and “When Sparrows build in Supper at the Mill” were among the most popular songs of the day. Her best-known poems include “The High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire” and “Divided”. Many, particularly her contemporaries, have defended her work. Gerald Massey described The High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire as “a poem full of power and tenderness” and Susan Coolidge remarked in a preface to an anthology of Ingelow’s poems, "She stood amid the morning dew/ And sang her earliest measure sweet/ Sang as the lark sings, speeding fair/ to touch and taste the purer air". “Sailing beyond Seas” (or “The Dove on the Mast”) was a favourite poem of Agatha Christie, who quotes it in two of her novels, The Moving Finger and Ordeal by Innocence. Still, the larger literary world largely dismissed her work. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, for example, wrote: "If we had nothing of Jean Ingelow’s but the most remarkable poem entitled Divided, it would be permissible to suppose the loss [of her], in fact or in might-have-been, of a poetess of almost the highest rank.... Jean Ingelow wrote some other good things, but nothing at all equalling this; while she also wrote too much and too long." Some of this criticism has overtones of dismissiveness of her as a female writer: “ Unless a man is an extraordinary coxcomb, a person of private means, or both, he seldom has the time and opportunity of committing, or the wish to commit, bad or indifferent verse for a long series of years; but it is otherwise with woman.” There have many parodies of her poetry, particularly of her archaisms, flowery language and perceived sentimentality. These include “Lovers, and a Reflexion” by Charles Stuart Calverley and “Supper at the Kind Brown Mill”, a parody of her “Supper at the Mill”, which appears in Gilbert Sorrentino’s satirical novel Blue Pastoral (1983). It is no longer fashionable to criticise poetry for the use of dialect.

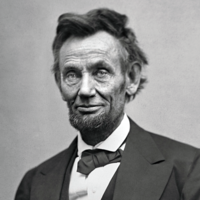

Horatio Alger Jr. (January 13, 1832 – July 18, 1899) was an American writer, best known for his many young adult novels about impoverished boys and their rise from humble backgrounds to lives of middle-class security and comfort through hard work, determination, courage, and honesty. His writings were characterized by the “rags-to-riches” narrative, which had a formative effect on the United States during the Gilded Age. All of Alger’s juvenile novels share essentially the same theme, known as the “Horatio Alger myth”: a teenage boy works hard to escape poverty. Often it is not hard work that rescues the boy from his fate but rather some extraordinary act of bravery or honesty. The boy might return a large sum of lost money or rescue someone from an overturned carriage. This brings the boy—and his plight—to the attention of a wealthy individual. Alger secured his literary niche in 1868 with the publication of his fourth book, Ragged Dick, the story of a poor bootblack’s rise to middle-class respectability. This novel was a huge success. His many books that followed were essentially variations on Ragged Dick and featured casts of stock characters: the valiant hard-working, honest youth, the noble mysterious stranger, the snobbish youth, and the evil, greedy squire. In the 1870s, Alger’s fiction was growing stale. His publisher suggested he tour the American West for fresh material to incorporate into his fiction. Alger took a trip to California, but the trip had little effect on his writing: he remained mired in the tired theme of “poor boy makes good.” The backdrops of these novels, however, became the American West rather than the urban environments of the northeastern United States. In the last decades of the 19th century, Alger’s moral tone coarsened with the change in boys’ tastes. Sensational thrills were wanted by the public. The Protestant work ethic had loosened its grip on the United States, and violence, murder, and other sensational themes entered Alger’s works. Public librarians questioned whether his books should be made available to the young. They were briefly successful, but interest in Alger’s novels was renewed in the first decades of the 20th century, and they sold in the thousands. By the time he died in 1899, Alger had published around a hundred volumes. He is buried in Natick, Massachusetts. Since 1947, the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans has awarded scholarships and prizes to deserving individuals. Biography Childhood: 1832–1847 Alger was born on January 13, 1832, in the New England coastal town of Chelsea, Massachusetts, the son of Horatio Alger Sr., a Unitarian minister, and Olive Augusta Fenno.He had many connections with the New England Puritan aristocracy of the early 19th century: He was the descendant of Pilgrim Fathers Robert Cushman, Thomas Cushman, and William Bassett. He was also the descendant of Sylvanus Lazell, a Minuteman and brigadier general in the War of 1812, and Edmund Lazell, a member of the Constitutional Convention in 1788.Horatio’s siblings Olive Augusta and James were born in 1833 and 1836, respectively. An invalid sister, Annie, was born in 1840, and a brother, Francis, in 1842. Alger was a precocious boy afflicted with myopia and asthma, but Alger Sr. decided early that his eldest son would one day enter the ministry, and, to that end, he tutored the boy in classical studies and allowed him to observe the responsibilities of ministering to parishioners.Alger began attending Chelsea Grammar School in 1842, but by December 1844 his father’s financial troubles had worsened considerably and, in search of a better salary, he moved the family to Marlborough, Massachusetts, an agricultural town 25 miles west of Boston, where he was installed as pastor of the Second Congregational Society in January 1845 with a salary sufficient to meet his needs. Horatio attended Gates Academy, a local preparatory school, and completed his studies at age 15. He published his earliest literary works in local newspapers. Harvard and early works: 1848–1864 In July 1848, Alger passed the Harvard entrance examinations and was admitted to the class of 1852. The 14-member, full-time Harvard faculty included Louis Agassiz and Asa Gray (sciences), Cornelius Conway Felton (classics), James Walker (religion and philosophy), and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (belles-lettres). Edward Everett served as president. Alger’s classmate Joseph Hodges Choate described Harvard at this time as “provincial and local because its scope and outlook hardly extended beyond the boundaries of New England; besides which it was very denominational, being held exclusively in the hands of Unitarians”. Alger thrived in the highly disciplined and regimented Harvard environment, winning scholastic and other prestigious awards. His genteel poverty and less-than-aristocratic heritage, however, barred him from membership in the Hasty Pudding Club and the Porcellian Club. In 1849 he became a professional writer when he sold two essays and a poem to the Pictorial National Library, a Boston magazine. He began reading Walter Scott, James Fenimore Cooper, Herman Melville, and other modern writers of fiction and cultivated a lifelong love for Longfellow, whose verse he sometimes employed as a model for his own. He was chosen Class Odist and graduated with Phi Beta Kappa Society honors in 1852, eighth in a class of 88.Alger had no job prospects following graduation, and returned home. He continued to write, submitting his work to religious and literary magazines, with varying success. He briefly attended Harvard Divinity School in 1853, possibly to be reunited with a romantic interest, but left in November 1853 to take a job as an assistant editor at the Boston Daily Advertiser. He loathed editing and quit in 1854 to teach at The Grange, a boys’ boarding school in Rhode Island. When The Grange suspended operations in 1856, Alger found employment directing the 1856 summer session at Deerfield Academy.His first book, Bertha’s Christmas Vision: An Autumn Sheaf, a collection of short pieces, was published in 1856, and his second book, Nothing to Do: A Tilt at Our Best Society, a lengthy satirical poem, was published in 1857. He attended Harvard Divinity School from 1857 to 1860, and upon graduation, toured Europe. In the spring of 1861, he returned to a nation in the throes of the Civil War. Exempted from military service for health reasons in July 1863, he wrote in support of the Union cause and associated with New England intellectuals. He was elected an officer in the New England Historic Genealogical Society in 1863.His first novel, Marie Bertrand: The Felon’s Daughter, was serialized in New York Weekly in 1864, and his first boys’ book, Frank’s Campaign, was published by A. K. Loring in Boston the same year. Alger initially wrote for adult magazines, including Harper’s Magazine and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, but a friendship with William Taylor Adams, a boys’ author, led him to write for the young. Ministry: 1864–1866 On December 8, 1864, Alger was installed as a pastor with the First Unitarian Church and Society of Brewster, Massachusetts. Between ministerial duties, he organized games and amusements for boys in the parish, railed against smoking and drinking, and organized and served as president of the local chapter of the Cadets for Temperance. He submitted stories to Student and Schoolmate, a boys’ monthly magazine of moral writings, edited by William Taylor Adams and published in Boston by Joseph H. Allen. In September 1865 his second boys’ book, Paul Prescott’s Charge, was published and received favorable reviews. Child sexual abuse Early in 1866 a church committee of men was formed to investigate reports that Alger had sexually molested boys. Church officials reported to the hierarchy in Boston that Alger had been charged with “the abominable and revolting crime of gross familiarity with boys”. Alger denied nothing, admitted he had been imprudent, considered his association with the church dissolved, and left town. Alger sent Unitarian officials in Boston a letter of remorse, and his father assured them his son would never seek another post in the church. The officials were satisfied and decided no further action would be taken. New York City: 1866–1896 Alger relocated to New York City, abandoned forever any thought of a career in the church, and focused instead on his writing. He wrote “Friar Anselmo” at this time, a poem that tells of a sinning cleric’s atonement through good deeds. He became interested in the welfare of the thousands of vagrant children who flooded New York City following the Civil War. He attended a children’s church service at Five Points, which led to “John Maynard”, a ballad about an actual shipwreck on Lake Erie, which brought Alger not only the respect of the literati but a letter from Longfellow. He published two poorly received adult novels, Helen Ford and Timothy Crump’s Ward. He fared better with stories for boys published in Student and Schoolmate and a third boys’ book, Charlie Codman’s Cruise.In January 1867 the first of 12 installments of Ragged Dick appeared in Student and Schoolmate. The story, about a poor bootblack’s rise to middle-class respectability, was a huge success. It was expanded and published as a novel in 1868. It proved to be his best-selling work. After Ragged Dick he wrote almost entirely for boys, and he signed a contract with publisher Loring for a Ragged Dick Series. In spite of the series’ success, Alger was on financially uncertain ground and tutored the five sons of the international banker Joseph Seligman. He wrote serials for Young Israel and lived in the Seligman home until 1876. In 1875 Alger produced the serial Shifting for Himself and Sam’s Chance, a sequel to The Young Outlaw. It was evident in these books that Alger had grown stale. Profits suffered, and he headed West for new material at Loring’s behest, arriving in California in February 1877. He enjoyed a reunion with his brother James in San Francisco and returned to New York late in 1877 on a schooner that sailed around Cape Horn. He wrote a few lackluster books in the following years, rehashing his established themes, but this time the tales were played before a Western background rather than an urban one.In New York, Alger continued to tutor the town’s aristocratic youth and to rehabilitate boys from the streets. He was writing both urban and Western-themed tales. In 1879, for example, he published The District Messenger Boy and The Young Miner. In 1877, Alger’s fiction became a target of librarians concerned about sensational juvenile fiction. An effort was made to remove his works from public collections, but the debate was only partially successful, defeated by the renewed interest in his work after his death.In 1881, Alger informally adopted Charlie Davis, a street boy, and another, John Downie, in 1883; they lived in Alger’s apartment. In 1881, he wrote a biography of President James A. Garfield but filled the work with contrived conversations and boyish excitements rather than facts. The book sold well. Alger was commissioned to write a biography of Abraham Lincoln, but again it was Alger the boys’ novelist opting for thrills rather than facts.In 1882, Alger’s father died. Alger continued to produce stories of honest boys outwitting evil, greedy squires and malicious youths. His work appeared in hardcover and paperback, and decades-old poems were published in anthologies. He led a busy life with street boys, Harvard classmates, and the social elite. In Massachusetts, he was regarded with the same reverence as Harriet Beecher Stowe. He tutored with never a whisper of scandal. Last years: 1896–1899 In the last two decades of the 19th century, the quality of Alger’s books deteriorated, and his boys’ works became nothing more than reruns of the plots and themes of his past. The times had changed, boys expected more, and a streak of violence entered Alger’s work. In The Young Bank Messenger, for example, a woman is throttled and threatened with death—an episode that would never have occurred in his earlier work.He attended the theater and Harvard reunions, read literary magazines, and wrote a poem at Longfellow’s death in 1892. His last novel for adults, The Disagreeable Woman, was published under the pseudonym Julian Starr. He took pleasure in the successes of the boys he had informally adopted over the years, retained his interest in reform, accepted speaking engagements, and read portions of Ragged Dick to boys’ assemblies.His popularity—and income—dwindled in the 1890s. In 1896, he had what he called a “nervous breakdown”; he relocated permanently to his sister’s home in South Natick, Massachusetts.He suffered from bronchitis and asthma for two years. He died on July 18, 1899, at the home of his sister in Natick, Massachusetts. His death was barely noticed. He is buried in the family lot at Glenwood Cemetery, South Natick, Massachusetts.Before his death, Alger asked Edward Stratemeyer to complete his unfinished works. In 1901, Young Captain Jack was completed by Stratemeyer and promoted as Alger’s last work. Alger once estimated that he earned only $100,000 between 1866 and 1896; at his death he had little money, leaving only small sums to family and friends. His literary work was bequeathed to his niece, to two boys he had casually adopted, and to his sister Olive Augusta, who destroyed his manuscripts and his letters, according to his wishes.Alger’s works received favorable comments and experienced a resurgence following his death. Until the advent of the Jazz Age in the 1920s, he sold about seventeen to twenty million volumes. In 1926, however, reader interest plummeted, and his major publisher ceased printing the books altogether. Surveys in 1932 and 1947 revealed very few children had read or even heard of Alger. The first Alger biography was a heavily fictionalized account published in 1928 by Herbert R. Mayes, who later admitted the work was a fraud. Legacy Since 1947, the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans has bestowed an annual award on “outstanding individuals in our society who have succeeded in the face of adversity” and scholarships “to encourage young people to pursue their dreams with determination and perseverance”.In 1982 to mark his 150th birthday, the Children’s Aid Society held a celebration. Helen M. Gray, the executive director of the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans, presented a selection of Alger’s books to Philip Coltoff, the Children’s Aid Society executive director.A 1982 musical, Shine!, was based on Alger’s work, particularly Ragged Dick and Silas Snobden’s Office Boy.In 2015, many of Alger’s books were published as illustrated paperbacks and ebooks under the title “Stories of Success” by Horatio Alger. In addition, Alger’s books were offered as dramatic audiobooks by the same publisher. Style and themes Alger scholar Gary Scharnhorst describes Alger’s style as “anachronistic”, “often laughable”, “distinctive”, and “distinguished by the quality of its literary allusions”. Ranging from the Bible and William Shakespeare (half of Alger’s books contain Shakespearean references) to John Milton and Cicero, the allusions he employed were a testament to his erudition. Scharnhorst credits these allusions with distinguishing Alger’s novels from pulp fiction.Scharnhorst describes six major themes in Alger’s boys’ books. The first, the Rise to Respectability, he observes, is evident in both his early and his late books, notably Ragged Dick, whose impoverished young hero declares, “I mean to turn over a new leaf, and try to grow up 'spectable.” His virtuous life wins him not riches but, more realistically, a comfortable clerical position and salary. The second major theme is Character Strengthened Through Adversity. In Strong and Steady and Shifting for Himself, for example, the affluent heroes are reduced to poverty and forced to meet the demands of their new circumstances. Alger occasionally cited the young Abe Lincoln as a representative of this theme for his readers. The third theme is Beauty versus Money, which became central to Alger’s adult fiction. Characters fall in love and marry on the basis of their character, talents, or intellect rather than the size of their bank accounts. In The Train Boy, for example, a wealthy heiress chooses to marry a talented but struggling artist, and in The Erie Train Boy a poor woman wins her true love despite the machinations of a rich, depraved suitor. Other major themes include the Old World versus the New. All of Alger’s novels have similar plots: a boy struggles to escape poverty through hard work and clean living. However, it is not always the hard work and clean living that rescue the boy from his situation, but rather a wealthy older gentleman, who admires the boy as a result of some extraordinary act of bravery or honesty that the boy has performed. For example, the boy rescues a child from an overturned carriage or finds and returns the man’s stolen watch. Often the older man takes the boy into his home as a ward or companion and helps him find a better job, sometimes replacing a less honest or less industrious boy. According to Scharnhorst, Alger’s father was “an impoverished man” who defaulted on his debts in 1844. His properties around Chelsea were seized and assigned to a local squire who held the mortgages. Scharnhorst speculates this episode in Alger’s childhood accounts for the recurrent theme in his boys’ books of heroes threatened with eviction or foreclosure and may account for Alger’s “consistent espousal of environmental reform proposals”. Scharnhorst writes, “Financially insecure throughout his life, the younger Alger may have been active in reform organizations such as those for temperance and children’s aid as a means of resolving his status-anxiety and establish his genteel credentials for leadership.”Alger scholar Edwin P. Hoyt notes that Alger’s morality “coarsened” around 1880, possibly influenced by the Western tales he was writing, because “the most dreadful things were now almost casually proposed and explored”. Although he continued to write for boys, Alger explored subjects like violence and “openness in the relations between the sexes and generations”; Hoyt attributes this shift to the decline of Puritan ethics in America.Scholar John Geck notes that Alger relied on “formulas for experience rather than shrewd analysis of human behavior”, and that these formulas were “culturally centered” and “strongly didactic”. Although the frontier society was a thing of the past during Alger’s career, Geck contends that “the idea of the frontier, even in urban slums, provides a kind of fairy tale orientation in which a Jack mentality can be both celebrated and critiqued”. He claims that Alger’s intended audience were youths whose “motivations for action are effectively shaped by the lessons they learn”. Geck notes that perception of the “pluck” characteristic of an Alger hero has changed over the decades. During the Jazz Age and the Great Depression, “the Horatio Alger plot was viewed from the perspective of Progressivism as a staunch defense of laissez-faire capitalism, yet at the same time criticizing the cutthroat business techniques and offering hope to a suffering young generation during the Great Depression”. By the Atomic Age, however “Alger’s hero was no longer a poor boy who, through determination and providence rose to middle-class respectability. He was instead the crafty street urchin who through quick wits and luck rose from impoverishment to riches”. Geck observes that Alger’s themes have been transformed in modern America from their original meanings into a male Cinderella myth and are an Americanization of the traditional Jack tales. Each story has its clever hero, its “fairy godmother”, and obstacles and hindrances to the hero’s rise. “However”, he writes, “the true Americanization of this fairy tale occurs in its subversion of this claiming of nobility; rather, the Alger hero achieves the American Dream in its nascent form, he gains a position of middle-class respectability that promises to lead wherever his motivation may take him”. The reader may speculate what Cinderella achieved as Queen and what an Alger hero attained once his middle-class status was stabilized, and "[i]t is this commonality that fixes Horatio Alger firmly in the ranks of modern adaptors of the Cinderella myth". Personal life Scharnhorst writes that Alger “exercised a certain discretion in discussing his probable homosexuality” and was known to have mentioned his sexuality only once after the Brewster incident. In 1870 the elder Henry James wrote that Alger “talks freely about his own late insanity—which he in fact appears to enjoy as a subject of conversation”. Although Alger was willing to speak to James, his sexuality was a closely guarded secret. According to Scharnhorst, Alger made veiled references to homosexuality in his boys’ books, and these references, Scharnhorst speculates, indicate Alger was “insecure with his sexual orientation”. Alger wrote, for example, that it was difficult to distinguish whether Tattered Tom was a boy or a girl and in other instances he introduces foppish, effeminate, lisping “stereotypical homosexuals” who are treated with scorn and pity by others. In Silas Snobden’s Office Boy, a kidnapped boy disguised as a girl is threatened with being sent to the “insane asylum” if he should reveal his actual sex. Scharnhorst believes Alger’s desire to atone for his “secret sin” may have “spurred him to identify his own charitable acts of writing didactic books for boys with the acts of the charitable patrons in his books who wish to atone for a secret sin in their past by aiding the hero”. Scharnhorst points out that the patron in Try and Trust, for example, conceals a “sad secret” from which he is redeemed only after saving the hero’s life.Alan Trachtenberg, in his introduction to the Signet Classic edition of Ragged Dick (1990), points out that Alger had tremendous sympathy for boys and discovered a calling for himself in the composition of boys’ books. “He learned to consult the boy in himself”, Trachtenberg writes, “to transmute and recast himself—his genteel culture, his liberal patrician sympathy for underdogs, his shaky economic status as an author, and not least, his dangerous erotic attraction to boys—into his juvenile fiction”. He observes that it is impossible to know whether Alger lived the life of a secret homosexual, "[b]ut there are hints that the male companionship he describes as a refuge from the streets—the cozy domestic arrangements between Dick and Fosdick, for example—may also be an erotic relationship". Trachtenberg observes that nothing prurient occurs in Ragged Dick but believes the few instances in Alger’s work of two boys touching or a man and a boy touching “might arouse erotic wishes in readers prepared to entertain such fantasies”. Such images, Trachtenberg believes, may imply “a positive view of homoeroticism as an alternative way of life, of living by sympathy rather than aggression”. Trachtenberg concludes, “in Ragged Dick we see Alger plotting domestic romance, complete with a surrogate marriage of two homeless boys, as the setting for his formulaic metamorphosis of an outcast street boy into a self-respecting citizen”. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horatio_Alger

Franz Wright (March 18, 1953– May 14, 2015) was an American poet. He and his father James Wright are the only parent/child pair to have won the Pulitzer Prize in the same category. Life and career Wright was born in Vienna, Austria. He graduated from Oberlin College in 1977. Wheeling Motel (Knopf, 2009), had selections put to music for the record Readings from Wheeling Motel. Wright wrote the lyrics to and performs the Clem Snide song "Encounter at 3AM" on the album Hungry Bird (2009). Wright’s most recent books include Kindertotenwald (Knopf, 2011), a collection of sixty-five prose poems concluding with a love poem to his wife, written while Wright had terminal lung cancer. The poem won Poetry magazine’s premier annual literary prize for best work published in the magazine during 2011. The prose poem collection was followed in 2012 by Buson: Haiku, a collection of translations of 30 haiku by the Japanese poet Yosa Buson, published in a limited edition of a few hundred copies by Tavern Books. . In 2013 Wright’s primary publisher, Knopf in New York, brought out another full length collection of verse and prose poems, F, which was begun in the ICU of a Boston hospital after excision of part of a lung. F was the most positively received to any of Wright’s work. Writing in the Huffington Post, Anis Shivani placed it among the best books of poetry yet produced by an American, and called Wright “our greatest contemporary poet.” In 2013 Wright recorded 15 prose poems from Kindertotenwald for inclusion in a series of improvisational concerts performed in European venues, arranged by David Sylvian, Stephan Mathieu and Christian Fennesz. Prior to his death, Wright had been working on a new manuscript. First its name was “Changed,” then “Axe in Blossom,” and has probably ended up taking the form of a chapbook available as of 2016, entitled, “The Toy Throne.” Wright has been anthologised in works such as The Best of the Best American Poetry as well as Czeslaw Milosz’s anthology A Book of Luminous Things Bearing the Mystery: Twenty Years of Image, and American Alphabets: 25 Contemporary Poets. Death Wright died of cancer at his home in Waltham, Massachusetts on May 14, 2015. Criticism Writing in the New York Review of Books, Helen Vendler said "Wright’s scale of experience, like Berryman’s, runs from the homicidal to the ecstatic... [His poems’] best forms of originality [are] deftness in patterning, startling metaphors, starkness of speech, compression of both pain and joy, and a stoic self-possession with the agonies and penalties of existence." Novelist Denis Johnson has said Wright’s poems “are like tiny jewels shaped by blunt, ruined fingers—miraculous gifts.” The Boston Review has called Wright’s poetry “among the most honest, haunting, and human being written today.” Critic Ernest Hilbert wrote for Random House’s magazine Bold Type that “Wright oscillates between direct and evasive dictions, between the barroom floor and the arts club podium, from aphoristic aside to icily poetic abstraction.” Walking to Martha’s Vineyard (2003) in particular, was well received. According to Publishers Weekly, the collection features "[h]eartfelt but often cryptic poems... fans will find Wright’s self-diagnostics moving throughout." The New York Times noted that Wright promises, and can deliver, great depths of feeling, while observing that Wright depends very much on our sense of his tone, and on our belief not just that he means what he says but that he has said something new...[on this score] Walking to Martha’s Vineyard sometimes succeeds.” Poet Jordan Davis, writing for The Constant Critic, suggested that Wright’s collection was so accomplished it would have to be kept “out of the reach of impulse kleptomaniacs.” Added Davis, “deader than deadpan, any particular Wright poem may not seem like much, until, that is, you read a few of them. Once the context kicks in, you may find yourself trying to track down every word he’s written.” Some critics were less welcoming. According to New Criterion critic William Logan, with whom Wright would later publicly feud, "[t]his poet is surprisingly vague about the specifics of his torment (most of his poems are shouts and curses in the dark). He was cruelly affected by the divorce of his parents, though perhaps after forty years there should be a statute of limitation... ‘The Only Animal,’ the most accomplished poem in the book, collapses into the same kitschy sanctimoniousness that puts nodding Jesus dolls on car dashboards." “Wright offers the crude, unprocessed sewage of suffering”, he comments. “He has drunk harder and drugged harder than any dozen poets in our health-conscious age, and paid the penalty in hospitals and mental wards.” The critical reception of Wright’s 2011 collection, Kindertotenwald (Knopf), has been positive on the whole. Writing in the Washington Independent Book Review, Grace Cavalieri speaks of the book as a departure from Wright’s best known poems. “The prose poems are intriguing thought patterns that show poetry as mental process... This is original material, and if a great poet cannot continue to be original, then he is really not all that great... In this text there is a joyfulness that energizes and makes us feel the writing as a purposeful surge. It is a life force. This is a good indicator of literary art... Memory and the past, mortality, longing, childhood, time, space, geography and loneliness, are all the poet’s playthings. In these conversations with himself, Franz Wright shows how the mind works with his feelings and his brain’s agility in its struggle with the heart.” Cultural critic for the Chicago Tribune Julia Keller says that Kindertotenwald is “ultimately about joy and grace and the possibility of redemption, about coming out whole on the other side of emotional catastrophe.” “This collection, like all of Wright’s book, combines familiar, colloquial phrases—the daily lingo you hear everywhere—with the sudden sharpness of a phrase you’ve never heard anywhere, but that sounds just as familiar, just as inevitable. These pieces are written in closely packed prose, like miniature short stories, but they have a fierce lilting beauty that marks them as poetry. Reading 'Kindertotenwald’ is like walking through a plate-glass window on purpose. There is—predictably—pain, but once you’ve made it a few steps past the threshold, you realize it wasn’t glass after all, only air, and that the shattering sound you heard was your own heart breaking. Healing, though, is possible. ”Soon, soon," the poet writes in “Nude With Handgun and Rosary,” “between one instant and the next, you will be well.” Awards * 1985, 1992 National Endowment for the Arts grant * 1989 Guggenheim Fellowship * 1991 Whiting Award * 1996 PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry * 2004 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, for Walking to Martha’s Vineyard Selected works * * The Writing, Argos Books, 2015, ISBN 978-1-938247-09-5 * F, Knopf, 2013 * Kindertotenwald Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, ISBN 978-0-307-27280-5 * "7 Prose", Marick Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1934851-17-3 * Wheeling Motel Alfred A. Knopf, 2009, ISBN 9780307265685 * Earlier Poems, Random House, Inc., 2007, ISBN 978-0-307-26566-1 * God’s Silence, Knopf, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4000-4351-4 * Walking to Martha’s Vineyard Alfred A. Knopf, 2003, ISBN 978-0-375-41518-0 * The Beforelife A.A. Knopf, 2001, ISBN 978-0-375-41154-0 * Knell Short Line Editions, 1999 * ILL LIT: Selected & New Poems Oberlin College Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-932440-83-9 * Rorschach test, Carnegie Mellon University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-88748-209-0 * The Night World and the Word Night Carnegie Mellon University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-88748-154-3 * Entry in an Unknown Hand Carnegie Mellon University Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0-88748-078-2 * Going North in Winter Gray House Press, 1986 * The One Whose Eyes Open When You Close Your Eyes Pym-Randall Press, 1982, ISBN 978-0-913219-35-5 * 8 Poems (1982) * The Earth Without You Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 1980, ISBN 9780914946236 * Tapping the White Cane of Solitude (1976) Translations * * The Unknown Rilke: Selected Poems, Rainer Maria Rilke, Translator Franz Wright, Oberlin College Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0-932440-56-3 * Valzhyna Mort: Factory of Tears (Copper Canyon Press, 2008) (translated from the Belarusian language in collaboration with the author and Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright) * “The Unknown Rilke: Expanded Edition” (1991) * “No Siege is Absolute: Versions of Rene Char” (1984) * "Buson: Haiku (2012) The Life of Mary (poems of R.M. Rilke) (1981) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Wright