Edmund Spenser (c. 1552 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for The Faerie Queene, an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognised as one of the premier craftsmen of Modern English verse in its infancy, and is considered one of the greatest poets in the English language. Edmund Spenser was born in East Smithfield, London, around the year 1552, though there is some ambiguity as to the exact date of his birth. As a young boy, he was educated in London at the Merchant Taylors' School and matriculated as a sizar at Pembroke College, Cambridge. While at Cambridge he became a friend of Gabriel Harvey and later consulted him, despite their differing views on poetry. In 1578 he became for a short time secretary to John Young, Bishop of Rochester. In 1579 he published The Shepheardes Calender and around the same time married his first wife, Machabyas Childe. In July 1580 Spenser went to Ireland in service of the newly appointed Lord Deputy, Arthur Grey, 14th Baron Grey de Wilton. When Grey was recalled to England, he stayed on in Ireland, having acquired other official posts and lands in the Munster Plantation. At some time between 1587 and 1589 he acquired his main estate at Kilcolman, near Doneraile in North Cork. Among his acquaintances in the area was Walter Raleigh, a fellow colonist. He later bought a second holding to the south, at Rennie, on a rock overlooking the river Blackwater in North Cork. Its ruins are still visible today. A short distance away grew a tree, locally known as "Spenser's Oak" until it was destroyed in a lightning strike in the 1960s. Local legend has it that he penned some of The Faerie Queene under this tree. In 1590 Spenser brought out the first three books of his most famous work, The Faerie Queene, having travelled to London to publish and promote the work, with the likely assistance of Raleigh. He was successful enough to obtain a life pension of £50 a year from the Queen. He probably hoped to secure a place at court through his poetry, but his next significant publication boldly antagonised the queen's principal secretary, Lord Burghley, through its inclusion of the satirical Mother Hubberd's Tale. He returned to Ireland. By 1594 Spenser's first wife had died, and in that year he married Elizabeth Boyle, to whom he addressed the sonnet sequence Amoretti. The marriage itself was celebrated in Epithalamion. In 1596 Spenser wrote a prose pamphlet titled, A View of the Present State of Ireland. This piece, in the form of a dialogue, circulated in manuscript, remaining unpublished until the mid-seventeenth century. It is probable that it was kept out of print during the author's lifetime because of its inflammatory content. The pamphlet argued that Ireland would never be totally 'pacified' by the English until its indigenous language and customs had been destroyed, if necessary by violence. Later on, during the Nine Years War in 1598, Spenser was driven from his home by the native Irish forces of Aodh Ó Néill. His castle at Kilcolman was burned, and Ben Jonson (who may have had private information) asserted that one of his infant children died in the blaze. In the year after being driven from his home, Spenser travelled to London, where he died aged forty-six. His coffin was carried to his grave in Westminster Abbey by other poets, who threw many pens and pieces of poetry into his grave with many tears. His second wife survived him and remarried twice. Rhyme and reason Thomas Fuller included in his Worthies of England a story that The Queen told her treasurer, William Cecil, to pay Spenser one hundred pounds for his poetry. The treasurer, however, objected that the sum was too much. She said, "Then give him what is reason". After a long while without receiving his payment, Spenser gave the Queen this quatrain on one of her progresses: I was promis'd on a time, To have a reason for my rhyme: From that time unto this season, I receiv'd nor rhyme nor reason. She immediately ordered the treasurer pay Spenser the original £100. This story seems to have attached itself to Spenser from Thomas Churchyard, who apparently had difficulty in getting payment of his pension (the only other one Elizabeth awarded to a poet). Spenser seems to have had no difficulty in receiving payment when it was due, the pension being collected for him by his publisher, Ponsonby. The Faerie Queene Spenser's masterpiece is the epic poem The Faerie Queene. The first three books of The Faerie Queene were published in 1590, and a second set of three books were published in 1596. Spenser originally indicated that he intended the poem to consist of twelve books, so the version of the poem we have today is incomplete. Despite this, it remains one of the longest poems in the English language. It is an allegorical work, and can be read (as Spenser presumably intended) on several levels of allegory, including as praise of Queen Elizabeth I. In a completely allegorical context, the poem follows several knights in an examination of several virtues. In Spenser's "A Letter of the Authors," he states that the entire epic poem is "cloudily enwrapped in allegorical devises," and that the aim behind The Faerie Queene was to “fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline.” Shorter poems Spenser published numerous relatively short poems in the last decade of the sixteenth century, almost all of which consider love or sorrow. In 1591 he published Complaints, a collection of poems that express complaints in mournful or mocking tones. Four years later, in 1595, Spenser published Amoretti and Epithalamion. This volume contains eighty-nine sonnets commemorating his courtship of Elizabeth Boyle. In “Amoretti,” Spenser uses subtle humour and parody while praising his beloved, reworking Petrarchism in his treatment of longing for a woman. “Epithalamion,” similar to “Amoretti,” deals in part with the unease in the development of a romantic and sexual relationship. It was written for his wedding to his young bride, Elizabeth Boyle. The poem consists of 365 long lines, corresponding to the days of the year; 68 short lines, claimed to represent the sum of the 52 weeks, 12 months, and 4 seasons of the annual cycle; and 24 stanzas, corresponding to the diurnal and sidereal hours.[citation needed] Some have speculated that the attention to disquiet in general reflects Spenser’s personal anxieties at the time, as he was unable to complete his most significant work, The Faerie Queene. In the following year Spenser released "Prothalamion," a wedding song written for the daughters of a duke, allegedly in hopes to gain favor in the court. The Spenserian stanza and sonnet Spenser used a distinctive verse form, called the Spenserian stanza, in several works, including The Faerie Queene. The stanza's main meter is iambic pentameter with a final line in iambic hexameter (having six feet or stresses, known as an Alexandrine), and the rhyme scheme is ababbcbcc. He also used his own rhyme scheme for the sonnet. Influences and influenced Though Spenser was well read in classical literature, scholars have noted that his poetry does not rehash tradition, but rather is distinctly his. This individuality may have resulted, to some extent, from a lack of comprehension of the classics. Spenser strove to emulate such ancient Roman poets as Virgil and Ovid, whom he studied during his schooling, but many of his best-known works are notably divergent from those of his predecessors.[15] The language of his poetry is purposely archaic, reminiscent of earlier works such as The Canterbury Tales of Geoffrey Chaucer and Il Canzoniere of Francesco Petrarca, whom Spenser greatly admired. Spenser was called a Poets' Poet and was admired by William Wordsworth, John Keats, Lord Byron, and Alfred Lord Tennyson, among others. Walter Raleigh wrote a dedicatory sonnet to The Faerie Queene in 1590, in which he claims to admire and value Spenser’s work more so than any other in the English language. In the eighteenth century, Alexander Pope compared Spenser to “a mistress, whose faults we see, but love her with them all." A View of the Present State of Ireland n his work A View of the present State of Ireland, Spenser devises his ideas to the issues of the nation of Ireland. These views are suspected to not be his own but based on the work of his predecessor, Lord Arthur Grey de Wilton who was appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1580 (Henley 19, 168-69). Lord Grey was a major figure in Ireland at the time and Spenser was influenced greatly by his ideals and his work in the country, as well as that of his fellow countrymen also living in Ireland at the time (Henley 169). The goal of this piece was to show that Ireland was in great need of reform. Spenser believed that “Ireland is a diseased portion of the State, it must first be cured and reformed, before it could be in a position to appreciate the good sound laws and blessings of the nation” (Henley 178). In A View of the present State of Ireland, Spenser categorizes the “evils” of the Irish people into three prominent categories: laws, customs, and religion (Spenser). These three elements work together in creating the disruptive and degraded people. One example given in the work is the native law system called “Brehon Law” which trumps the established law given by the English monarchy (Spenser). This system has its own court and way of dealing with infractions. It has been passed down through the generations and Spenser views this system as a native backward custom which must be destroyed. Spenser also recommended scorched earth tactics, such as he had seen used in the Desmond Rebellions, to create famine. Although it has been highly regarded as a polemical piece of prose and valued as a historical source on 16th century Ireland, the View is seen today as genocidal in intent. Spenser did express some praise for the Gaelic poetic tradition, but also used much tendentious and bogus analysis to demonstrate that the Irish were descended from barbarian Scythian stock. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Spenser

George Meredith, OM (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and poet of the Victorian era. Meredith was born in Portsmouth, England, a son and grandson of naval outfitters. His mother died when he was five. At the age of 14 he was sent to a Moravian School in Neuwied, Germany, where he remained for two years. He read law and was articled as a solicitor, but abandoned that profession for journalism and poetry. He collaborated with Edward Gryffydh Peacock, son of Thomas Love Peacock in publishing a privately circulated literary magazine, the Monthly Observer. He married Edward Peacock's widowed sister Mary Ellen Nicolls in 1849 when he was twenty-one years old and she was twenty-eight. He collected his early writings, first published in periodicals, into Poems, published to some acclaim in 1851. His wife ran off with the English Pre-Raphaelite painter Henry Wallis [1830–1916] in 1858; she died three years later. The collection of "sonnets" entitled Modern Love (1862) came of this experience as did The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, his first "major novel". He married Marie Vulliamy in 1864 and settled in Surrey. He continued writing novels and poetry, often inspired by nature. His writing was characterised by a fascination with imagery and indirect references. He had a keen understanding of comedy and his Essay on Comedy (1877) is still quoted in most discussions of the history of comic theory. In The Egoist, published in 1879, he applies some of his theories of comedy in one of his most enduring novels. Some of his writings, including The Egoist, also highlight the subjugation of women during the Victorian period. During most of his career, he had difficulty achieving popular success. His first truly successful novel was Diana of the Crossways published in 1885. Meredith supplemented his often uncertain writer's income with a job as a publisher's reader. His advice to Chapman and Hall made him influential in the world of letters. His friends in the literary world included, at different times, William and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Leslie Stephen, Robert Louis Stevenson, George Gissing and J. M. Barrie. His contemporary Sir Arthur Conan Doyle paid him homage in the short-story The Boscombe Valley Mystery, when Sherlock Holmes says to Dr. Watson during the discussion of the case, "And now let us talk about George Meredith, if you please, and we shall leave all minor matters until to-morrow." Oscar Wilde, in his dialogue The Decay of Lying, implies that Meredith, along with Balzac, is his favourite novelist, saying "Ah, Meredith! Who can define him? His style is chaos illumined by flashes of lightning". In 1868 he was introduced to Thomas Hardy by Frederick Chapman of Chapman & Hall the publishers. Hardy had submitted his first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady. Meredith advised Hardy not to publish his book as it would be attacked by reviewers and destroy his hopes of becoming a novelist. Meredith felt the book was too bitter a satire on the rich and counselled Hardy to put it aside and write another 'with a purely artistic purpose' and more of a plot. Meredith spoke from experience; his first big novel, The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, was judged so shocking that Mudie's circulating library had cancelled an order of 300 copies. Hardy continued to try and publish the novel: however it remained unpublished, though he clearly took Meredith's advice seriously. Before his death, Meredith was honoured from many quarters: he succeeded Lord Tennyson as president of the Society of Authors; in 1905 he was appointed to the Order of Merit by King Edward VII. In 1909, he died at his home in Box Hill, Surrey. Works Essays * Essay on Comedy (1877) Novels * The Shaving of Shagpat (1856) * Farina (1857) * The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (1859) * Evan Harrington (1861) * Emilia in England (1864), republished as Sandra Belloni in 1887 * Rhoda Fleming (1865) * Vittoria (1867) * The Adventures of Harry Richmond (1871) * Beauchamp's Career (1875) * The House on the Beach (1877) * The Case of General Ople and Lady Camper (1877) * The Tale of Chloe (1879) * The Egoist (1879) * The Tragic Comedians (1880) * Diana of the Crossways (1885) * One of our Conquerors (1891) * Lord Ormont and his Aminta (1894) * The Amazing Marriage (1895) * Celt and Saxon (1910) Poetry * Poems (1851) * Modern Love (1862) * Poems and Lyrics of the Joy of Earth (1883) * The Woods of Westermain (1883) * A Faith on Trial (1885) * Ballads and Poems of Tragic Life (1887) * A Reading of Earth (1888) * The Empty Purse (1892) * Odes in Contribution to the Song of French History(1898) * A Reading of Life (1901) * Last Poems (1909) * Lucifer in Starlight * The Lark Ascending (the inspiration for Vaughan Williams' instrumental work The Lark Ascending). References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Meredith

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet, the son of a farm labourer, who came to be known for his celebratory representations of the English countryside and his lamentation of its disruption. His poetry underwent a major re-evaluation in the late 20th century and he is often now considered to be among the most important 19th-century poets. His biographer Jonathan Bate states that Clare was "the greatest labouring-class poet that England has ever produced. No one has ever written more powerfully of nature, of a rural childhood, and of the alienated and unstable self”. Early life Clare was born in Helpston, six miles to the north of the city of Peterborough. In his life time, the village was in the Soke of Peterborough in Northamptonshire and his memorial calls him "The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Helpston now lies in the Peterborough unitary authority of Cambridgeshire. He became an agricultural labourer while still a child; however, he attended school in Glinton church until he was twelve. In his early adult years, Clare became a pot-boy in the Blue Bell public house and fell in love with Mary Joyce; but her father, a prosperous farmer, forbade her to meet him. Subsequently he was a gardener at Burghley House. He enlisted in the militia, tried camp life with Gypsies, and worked in Pickworth as a lime burner in 1817. In the following year he was obliged to accept parish relief. Malnutrition stemming from childhood may be the main culprit behind his 5-foot stature and may have contributed to his poor physical health in later life. Early poems Clare had bought a copy of Thomson's Seasons and began to write poems and sonnets. In an attempt to hold off his parents' eviction from their home, Clare offered his poems to a local bookseller named Edward Drury. Drury sent Clare's poetry to his cousin John Taylor of the publishing firm of Taylor & Hessey, who had published the work of John Keats. Taylor published Clare's Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery in 1820. This book was highly praised, and in the next year his Village Minstrel and other Poems were published. Midlife He had married Martha ("Patty") Turner in 1820. An annuity of 15 guineas from the Marquess of Exeter, in whose service he had been, was supplemented by subscription, so that Clare became possessed of £45 annually, a sum far beyond what he had ever earned. Soon, however, his income became insufficient, and in 1823 he was nearly penniless. The Shepherd's Calendar (1827) met with little success, which was not increased by his hawking it himself. As he worked again in the fields his health temporarily improved; but he soon became seriously ill. Earl FitzWilliam presented him with a new cottage and a piece of ground, but Clare could not settle in his new home. Clare was constantly torn between the two worlds of literary London and his often illiterate neighbours; between the need to write poetry and the need for money to feed and clothe his children. His health began to suffer, and he had bouts of severe depression, which became worse after his sixth child was born in 1830 and as his poetry sold less well. In 1832, his friends and his London patrons clubbed together to move the family to a larger cottage with a smallholding in the village of Northborough, not far from Helpston. However, he felt only more alienated. His last work, the Rural Muse (1835), was noticed favourably by Christopher North and other reviewers, but this was not enough to support his wife and seven children. Clare's mental health began to worsen. As his alcohol consumption steadily increased along with his dissatisfaction with his own identity, Clare's behaviour became more erratic. A notable instance of this behaviour was demonstrated in his interruption of a performance of The Merchant of Venice, in which Clare verbally assaulted Shylock. He was becoming a burden to Patty and his family, and in July 1837, on the recommendation of his publishing friend, John Taylor, Clare went of his own volition (accompanied by a friend of Taylor's) to Dr Matthew Allen's private asylum High Beach near Loughton, in Epping Forest. Taylor had assured Clare that he would receive the best medical care. Later life and death During his first few asylum years in Essex (1837–1841), Clare re-wrote famous poems and sonnets by Lord Byron. His own version of Child Harold became a lament for past lost love, and Don Juan, A Poem became an acerbic, misogynistic, sexualised rant redolent of an aging Regency dandy. Clare also took credit for Shakespeare's plays, claiming to be the Renaissance genius himself. "I'm John Clare now," the poet claimed to a newspaper editor, "I was Byron and Shakespeare formerly." In 1841, Clare left the asylum in Essex, to walk home, believing that he was to meet his first love Mary Joyce; Clare was convinced that he was married with children to her and Martha as well. He did not believe her family when they told him she had died accidentally three years earlier in a house fire. He remained free, mostly at home in Northborough, for the five months following, but eventually Patty called the doctors in. Between Christmas and New Year in 1841, Clare was committed to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum (now St Andrew's Hospital). Upon Clare's arrival at the asylum, the accompanying doctor, Fenwick Skrimshire, who had treated Clare since 1820, completed the admission papers. To the enquiry "Was the insanity preceded by any severe or long-continued mental emotion or exertion?", Dr Skrimshire entered: "After years of poetical prosing." He remained here for the rest of his life under the humane regime of Dr Thomas Octavius Prichard, encouraged and helped to write. Here he wrote possibly his most famous poem, I Am. He died on 20 May 1864, in his 71st year. His remains were returned to Helpston for burial in St Botolph’s churchyard. Today, children at the John Clare School, Helpston's primary, parade through the village and place their 'midsummer cushions' around Clare's gravestone (which has the inscriptions "To the Memory of John Clare The Northamptonshire Peasant Poet" and "A Poet is Born not Made") on his birthday, in honour of their most famous resident. The thatched cottage where he was born was bought by the John Clare Education & Environment Trust in 2005 and is restoring the cottage to its 18th century state. Poetry In his time, Clare was commonly known as "the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". Since his formal education was brief, Clare resisted the use of the increasingly standardised English grammar and orthography in his poetry and prose. Many of his poems would come to incorporate terms used locally in his Northamptonshire dialect, such as 'pooty' (snail), 'lady-cow' (ladybird), 'crizzle' (to crisp) and 'throstle' (song thrush). In his early life he struggled to find a place for his poetry in the changing literary fashions of the day. He also felt that he did not belong with other peasants. Clare once wrote "I live here among the ignorant like a lost man in fact like one whom the rest seemes careless of having anything to do with—they hardly dare talk in my company for fear I should mention them in my writings and I find more pleasure in wandering the fields than in musing among my silent neighbours who are insensible to everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose.” It is common to see an absence of punctuation in many of Clare's original writings, although many publishers felt the need to remedy this practice in the majority of his work. Clare argued with his editors about how it should be presented to the public. Clare grew up during a period of massive changes in both town and countryside as the Industrial Revolution swept Europe. Many former agricultural workers, including children, moved away from the countryside to over-crowded cities, following factory work. The Agricultural Revolution saw pastures ploughed up, trees and hedges uprooted, the fens drained and the common land enclosed. This destruction of a centuries-old way of life distressed Clare deeply. His political and social views were predominantly conservative ("I am as far as my politics reaches 'King and Country'—no Innovations in Religion and Government say I."). He refused even to complain about the subordinate position to which English society relegated him, swearing that "with the old dish that was served to my forefathers I am content." His early work delights both in nature and the cycle of the rural year. Poems such as Winter Evening, Haymaking and Wood Pictures in Summer celebrate the beauty of the world and the certainties of rural life, where animals must be fed and crops harvested. Poems such as Little Trotty Wagtail show his sharp observation of wildlife, though The Badger shows his lack of sentiment about the place of animals in the countryside. At this time, he often used poetic forms such as the sonnet and the rhyming couplet. His later poetry tends to be more meditative and use forms similar to the folks songs and ballads of his youth. An example of this is Evening. His knowledge of the natural world went far beyond that of the major Romantic poets. However, poems such as I Am show a metaphysical depth on a par with his contemporary poets and many of his pre-asylum poems deal with intricate play on the nature of linguistics. His 'bird's nest poems', it can be argued, illustrate the self-awareness, and obsession with the creative process that captivated the romantics. Clare was the most influential poet, aside from Wordsworth to practice in an older style. Revival of interest in the twentieth century Clare was relatively forgotten during the later nineteenth century, but interest in his work was revived by Arthur Symons in 1908, Edmund Blunden in 1920 and John and Anne Tibble in their ground-breaking 1935 2-volume edition. Benjamin Britten set some of 'May' from A Shepherd's Calendar in his Spring Symphony of 1948, and included a setting of The Evening Primrose in his Five Flower Songs Copyright to much of his work has been claimed since 1965 by the editor of the Complete Poetry (OUP, 9 vols., 1984–2003), Professor Eric Robinson though these claims were contested. Recent publishers have refused to acknowledge the claim (especially in recent editions from Faber and Carcanet) and it seems the copyright is now defunct. The John Clare Trust purchased Clare Cottage in Helpston in 2005, preserving it for future generations. In May 2007 the Trust gained £1.m of funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and commissioned Jefferson Sheard Architects to create the new landscape design and Visitor Centre, including a cafe, shop and exhibition space. The Cottage has been restored using traditional building methods and opened to the public. The largest collection of original Clare manuscripts are housed at Peterborough Museum, where they are available to view by appointment. Since 1993, the John Clare Society of North America has organised an annual session of scholarly papers concerning John Clare at the annual Convention of the Modern Language Association of America. Poetry collections by Clare (chronological) * Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. London, 1820. * The Village Minstrel, and Other Poems. London, 1821. * The Shepherd's Calendar with Village Stories and Other Poems. London, 1827 * The Rural Muse. London, 1835. * Sonnet. London 1841 * First Love * Snow Storm. * The Firetail. * The Badger – Time unknown References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Clare

Dolores Veintimilla de Galindo (Quito, 12 de julio de 1829 - Cuenca, 23 de mayo de 1857) fue una poeta ecuatoriana del siglo XIX. Durante su corta vida fue la creadora de poemas de corte romántico que están cargados de elementos que asocian a la mujer con el papel de víctima asociados con sentimientos de dolor, tristeza, anhelo del pasado, amores frustrado y pesimismo. Fue influenciada por la formación de la subjetividad femenina de su época. Su poema “Quejas” está lleno de esos sentimientos que reflejan su estado anímico. El fracaso en su matrimonio con el médico colombiano Sixto Galindo, así como su pensamiento feminista adelantado a la época, marcarían la personalidad y los trabajos posteriores de Dolores. La persecución e incomprensión de la sociedad cuencana la llevó al suicidio.

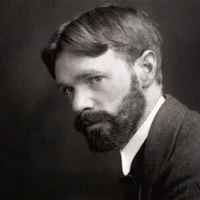

David Herbert Richards Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic and painter who published as D. H. Lawrence. His collected works represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. In them, Lawrence confronts issues relating to emotional health and vitality, spontaneity, and instinct. Lawrence’s opinions earned him many enemies and he endured official persecution, censorship, and misrepresentation of his creative work throughout the second half of his life, much of which he spent in a voluntary exile which he called his “savage pilgrimage”. At the time of his death, his public reputation was that of a pornographer who had wasted his considerable talents. E. M. Forster, in an obituary notice, challenged this widely held view, describing him as, “The greatest imaginative novelist of our generation”. Later, the influential Cambridge critic F. R. Leavis championed both his artistic integrity and his moral seriousness, placing much of Lawrence's fiction within the canonical “great tradition” of the English novel. Lawrence is now valued by many as a visionary thinker and significant representative of modernism in English literature.

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

George Henry Boker (October 6, 1823 – January 2, 1890) was an American poet, playwright, and diplomat. Boker was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His father was Charles S. Boker, a wealthy banker, whose financial expertness weathered the Girard National Bank through the panic years of 1838-40, and whose honour, impugned after his 1857 death, was defended many years later by his son in “The Book of the Dead.” Charles Boker was also a director of the Mechanics National Bank.

I am from Cecina in Tuscany, Italy. I moved to Davis, California, in 2009. My life experience in Davis has inspired many of my recent poems. I write my poetry only in Italian language. During the last few summer seasons I have been actively sharing my poems in Tuscany where I participate frequently in cultural and poetry events. As a child, after recognizing that I had a gift for poetry, my parents submitted my work in a variety of different contests. In 1989 I won my first prize. Starting in 1998, I published my poetry in newspapers and magazines, mostly in the area of Tuscany where I was raised. My first book, "Sono un Angelo Dimenticato," was published in 1998 from Ed.La Palma; in 2008 a second book, called "Nessuna Musa di Cristallo” was also published. My poem “Sto per lasciare tutto “(English version: “I’m about to leave everything”) was published in USA, for the Davis Poetry Book 2011. My books: "Extreme Fishing" 2011, "I colori dentro" 2016, both available on Amazon. "Sospesa fra due mondi" was published in Italy by Mds Editore, 2019. In 2020 I moved back to my country and I live in Turin where I work as a teacher.

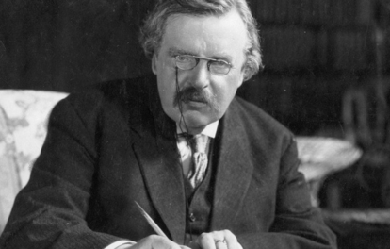

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, Time observed: "Whenever possible Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out." Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brown, and wrote on apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognised the wide appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an "orthodox" Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting to Roman Catholicism from high church Anglicanism. Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, John Henry Newman and John Ruskin.

Edgar Lee Masters (August 23, 1868– March 5, 1950) was an American attorney, poet, biographer, and dramatist. He is the author of Spoon River Anthology, The New Star Chamber and Other Essays, Songs and Satires, The Great Valley, The Serpent in the Wilderness An Obscure Tale, The Spleen, Mark Twain: A Portrait, Lincoln: The Man, and Illinois Poems. In all, Masters published twelve plays, twenty-one books of poetry, six novels and six biographies, including those of Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain, Vachel Lindsay, and Walt Whitman. Life and career Born in Garnett, Kansas to attorney Hardin Wallace Masters and Emma J. Dexter, his father had briefly moved to set up a law practice, then soon moved back to his paternal grandparents’ farm near Petersburg in Menard County, Illinois. In 1880 they moved to Lewistown, Illinois, where he attended high school and had his first publication in the Chicago Daily News. The culture around Lewistown, in addition to the town’s cemetery at Oak Hill, and the nearby Spoon River were the inspirations for many of his works, most notably Spoon River Anthology, his most famous and acclaimed work. He attended Knox Academy in 1889–90, a now defunct preparatory program run by Knox College, but was forced to leave due to his family’s inability to finance his education. After working in his father’s law office, he was admitted to the Illinois bar and moved to Chicago, where he established a law partnership in 1893 with the law firm of Kickham Scanlan. He married twice. In 1898 he married Helen M. Jenkins, the daughter of Robert Edwin Jenkins, a lawyer in Chicago, and had three children. During his law partnership with Clarence Darrow from 1903 to 1908, Masters defended the poor. In 1911 he started his own law firm, despite three years of unrest (1908–11) caused by extramarital affairs and an argument with Darrow. Two of his children followed him with literary careers. His daughter Marcia pursued poetry, while his son Hilary Masters became a novelist. Hilary and his half-brother Hardin wrote a memoir of their father. Masters died at a nursing home on March 5, 1950, in Melrose Park, Pennsylvania, age 81. He is buried in Oakland cemetery in Petersburg, Illinois. His epitaph includes his poem, “To-morrow is My Birthday” from Toward the Gulf (1918): Good friends, let’s to the fields…After a little walk and by your pardon, I think I’ll sleep, there is no sweeter thing.Nor fate more blessed than to sleep. I am a dream out of a blessed sleep-Let’s walk, and hear the lark. Family history Edgar’s father was Hardin Wallace Masters, whose father was Squire Davis Masters, whose father was Thomas Masters, whose father was Hillery Masters, the son of Robert Masters (born c. 1715, Prince George’s County, Maryland, the son of William W. Masters and wife Mary Veatch Masters). Edgar Lee Masters wrote in his autobiography, Across Spoon River (1936), that his ancestor Hillery Masters was the son of “Knotteley” Masters, but family genealogies show that Hillery and Notley Masters were, in fact, brothers. Poetry Masters first published his early poems and essays under the pseudonym Dexter Wallace (after his mother’s maiden name and his father’s middle name) until the year 1903, when he joined the law firm of Clarence Darrow. Masters began developing as a notable American poet in 1914, when he began a series of poems (this time under the pseudonym Webster Ford) about his childhood experiences in Western Illinois, which appeared in Reedy’s Mirror, a St. Louis publication. In 1915 the series was bound into a volume and re-titled Spoon River Anthology. Years later, he wrote a memorable and invaluable account of the book’s background and genesis, his working methods and influences, as well as its reception by the critics, favorable and hostile, in an autobiographical article notable for its human warmth and general interest. Although he never matched the success of his Spoon River Anthology, he did publish several other volumes of poems including Book of Verses in 1898, Songs and Sonnets in 1910, The Great Valley in 1916, Song and Satires in 1916, The Open Sea in 1921, The New Spoon River in 1924, Lee in 1926, Jack Kelso in 1928, Lichee Nuts in 1930, Gettysburg, Manila, Acoma in 1930, Godbey, sequel to Jack Kelso in 1931, The Serpent in the Wilderness in 1933, Richmond in 1934, Invisible Landscapes in 1935, The Golden Fleece of California in 1936, Poems of People in 1936, The New World in 1937, More People in 1939, Illinois Poems in 1941, and Along the Illinois in 1942. Lincoln: the Man In 1931 Masters published the biography Lincoln: the Man, which demythologizes Abraham Lincoln, portraying him as a tool of bankers wanting a new Bank of the United States, “that political system which doles favors to the strong in order to win and keep their adherence to the government”, and advocates “a people taxed to make profits for enterprises that cannot stand alone”. He claimed the Whig Party led by Lincoln’s mentor Henry Clay “had no platform to announce because its principles were plunder and nothing else.” Quotations from the book: “The political history of America has been written for the most part by those who were unfriendly to the theory of a confederated republic, or who did not understand it. It has been written by devotees of the protective principle [tariff], by centralists, and to a large degree by New England.” “For in six weeks he was to inaugurate a war without the American people having anything to say about it. He was to call for and send troops into the South, and thus stir that psychology of hate and fear from which a people cannot extricate themselves, though knowing and saying that the war was started by usurpation. Did he mean that he would bow to the American people when the law was laid down by their courts, through which alone the law be interpreted as the Constitutional voice of the people? No, he did not mean that; because when Taney decided that Lincoln had no power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, Lincoln flouted and trampled the decision of the court.” “The War between the States demonstrated that salvation is not of the Jews, but of the Greeks. The World War added to this proof; for Wilson did many things that Lincoln did, and with Lincoln as authority for doing them. Perhaps it will happen again that a few men, deciding what is a cause of war, and what is necessary to its successful prosecution, may, as Lincoln and Wilson did, seal the lips of discussion and shackle the press; but no less the ideal of a just state, which has founded itself in reason and in free speech, will remain.” Notable works Poetry * A Book of Verses (1898) * Songs and Sonnets (1910) * Spoon River Anthology (1915) * Songs and Satires (1916) * Fiddler Jones (1916) * The Great Valley (New York: Macmillan Co., 1916) * Toward the Gulf (New York: Macmillan Co., 1918) * Starved Rock (New York: Macmillan Co., 1919) * Jack Kelso: A Dramatic Poem (1920) * Domesday Book (New York: Macmillan Co., 1920) * The Open Sea (New York: Macmillan Co., 1921) * The New Spoon River (New York: Macmillan Co., 1924) * Selected Poems (1925) * Lichee-Nut Poems (American Mercury, Jan. 1925) * Lee: A Dramatic Poem (1926) * Godbey: A Dramatic Poem (1931), sequel to Jack Kelso (1920) * The Serpent in the Wilderness (1933) * Richmond: A Dramatic Poem (1934) * Invisible Landscapes (1935) * Poems of People (1936) * The Golden Fleece of California (1936) (poetic narrative) * The New World (1937) * More People (1939) * Illinois Poems (1941) * Along the Illinois (1942) * Silence (1946) * George Gray * Many Soldiers * The Unknown Biographies * Children of the Market Place: A Fictitious Autobiography (New York: Macmillan Co., 1922). Life of Stephen Douglas. * Levy Mayer and the New Industrial Era (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927). Chicago attorney Levy Mayer (1858-1922). * Lincoln: The Man (1931) * Vachel Lindsay: A Poet in America (1935) * Across Spoon River: An Autobiography (memoir) (1936) * Whitman (1937) * Mark Twain: A Portrait (1938) Books * The New Star Chamber and Other Essays (1904) * The Blood of the Prophets (1905) (play) * Althea (1907) (play) * The Trifler (1908) (play) * Mitch Miller (novel) (1920) * Skeeters Kirby (novel) (1923) * The Nuptial Flight (novel) (1923) * Kit O’Brien (novel) (1927) * The Fate of the Jury: An Epilogue to Domesday Book (1929) * Gettysburg, Manila, Acoma: Three Plays (1930) * The Tale of Chicago (1933) * The Tide of Time (novel) (1937) * The Sangamon (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1942, 1988) Awards & honors Masters was awarded the Mark Twain Silver Medal in 1936, the Poetry Society of America medal in 1941, the Academy of American Poets Fellowship in 1942, and the Shelly Memorial Award in 1944. In 2014, he was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Lee_Masters

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (17 August 1840– 10 September 1922) (sometimes spelled “Wilfred”) was an English poet and writer. He and his wife, Lady Anne Blunt travelled in the Middle East and were instrumental in preserving the Arabian horse bloodlines through their farm, the Crabbet Arabian Stud. He was best known for his poetry, which was published in a collected edition in 1914, but also wrote a number of political essays and polemics. Blunt is also known for his views against imperialism, viewed as relatively enlightened for his time. Early life Blunt was born at Petworth House in Sussex and served in the Diplomatic Service from 1858 to 1869. He was raised in the faith of his mother, a Catholic convert, and educated at Twyford School, Stonyhurst, and at St Mary’s College, Oscott. His most memorable line of poetry on the subject comes from Satan Absolved (1899), where the devil, answering a Kiplingesque remark by God, snaps back: ‘The white man’s burden, Lord, is the burden of his cash’ Here, Longford explains, 'Blunt stood Rudyard Kipling’s familiar concept on its head, arguing that the imperialists’ burden is not their moral responsibility for the colonised peoples, but their urge to make money out of them.' Personal life In 1869, Blunt married Lady Anne Noel, the daughter of the Earl of Lovelace and Ada Lovelace, and granddaughter of Lord Byron. Together the Blunts travelled through Spain, Algeria, Egypt, the Syrian Desert, and extensively in the Middle East and India. Based upon pure-blooded Arabian horses they obtained in Egypt and the Nejd, they co-founded Crabbet Arabian Stud, and later purchased a property near Cairo, named Sheykh Obeyd which housed their horse breeding operation in Egypt. In 1882, he championed the cause of Urabi Pasha, which led him to be banned from entering Egypt for four years. Blunt generally opposed British imperialism as a matter of philosophy, and his support for Irish causes led to his imprisonment in 1888. Wilfrid and Lady Anne’s only child to live to maturity was Judith Blunt-Lytton, 16th Baroness Wentworth, later known as Lady Wentworth. As an adult, she was married in Cairo but moved permanently to the Crabbet Park Estate in 1904. Wilfrid had a number of mistresses, among them a long term relationship with the courtesan Catherine “Skittles” Walters, and the Pre-Raphaelite beauty, Jane Morris. Eventually, he moved another mistress, Dorothy Carleton, into his home. This event triggered Lady Anne’s legal separation from him in 1906. At that time, Lady Anne signed a Deed of Partition drawn up by Wilfrid. Under its terms, unfavourable to Lady Anne, she kept the Crabbet Park property (where their daughter Judith lived) and half the horses, while Blunt took Caxtons Farm, also known as Newbuildings, and the rest of the stock. Always struggling with financial concerns and chemical dependency issues, Wilfrid sold off numerous horses to pay debts and constantly attempted to obtain additional assets. Lady Anne left the management of her properties to Judith, and spent many months of every year in Egypt at the Sheykh Obeyd estate, moving there permanently in 1915. Due primarily to the manoeuvering of Wilfrid in an attempt to disinherit Judith and obtain the entire Crabbet property for himself, Judith and her mother were estranged at the time of Lady Anne’s death in 1917. As a result, Lady Anne’s share of the Crabbet Stud passed to Judith’s daughters, under the oversight of an independent trustee. Blunt filed a lawsuit soon afterward. Ownership of the Arabian horses went back and forth between the estates of father and daughter in the following years. Blunt sold more horses to pay off debts and shot at least four in an attempt to spite his daughter, an action which required intervention of the trustee of the estate with a court injunction to prevent him from further “dissipating the assets” of the estate. The lawsuit was settled in favour of the granddaughters in 1920, and Judith bought their share from the trustee, combining it with her own assets and reuniting the stud. Father and daughter briefly reconciled shortly before Wilfrid Scawen Blunt’s death in 1922, but his promise to rewrite his will to restore Judith’s inheritance never materialised. Blunt was a friend of Winston Churchill, aiding him in his 1906 biography of his father, Randolph Churchill, whom Blunt had befriended years earlier in 1883 at a chess tournament. Work in Africa In the early 1880s, Britain was struggling with its Egyptian colony. Wilfrid Blunt was sent to notify Sir Edward Malet, the British agent, as to the Egyptian public opinion concerning the recent changes in government and development policies. In mid-December 1881, Blunt met with Ahmed ‘Urabi, known as Arabi or 'El Wahid’ (the Only One) due to his popularity with the Egyptians. Arabi was impressed with Blunt’s enthusiasm and appreciation of his culture. Their mutual respect created an environment in which Arabi could peacefully explain the reasoning behind a new patriotic movement, 'Egypt for the Egyptians’. Over the course of several days, Arabi explained the complicated background of the revolutionaries and their determination to rid themselves of the Turkish oligarchy. Wilfrid Blunt was vital in the relay of this information to the British empire although his anti-imperialist views were disregarded and England mounted further campaigns in the Sudan in 1885 and 1896–98. Egyptian Garden scandal In 1901, a pack of fox hounds was shipped over to Cairo to entertain the army officers, and subsequently a foxhunt took place in the desert near Cairo. The fox was chased into Blunt’s garden, and the hounds and hunt followed it. As well as a house and garden, the land contained the Blunt’s Sheykh Obeyd stud farm, housing a number of valuable Arabian horses. Blunt’s staff challenged the trespassers– who, though army officers, were not in uniform– and beat them when they refused to turn back. For this, the staff were accused of assault against army officers and imprisoned. Blunt made strenuous efforts to free his staff, much to the embarrassment of the British army officers and civil servants involved. Bibliography * Sonnets and Songs. By Proteus. John Murray, 1875 * Aubrey de Vere (ed.): Proteus and Amadeus: A Correspondence Kegan Paul, 1878 * The Love Sonnets of Proteus. Kegan Paul, 1881 * The Future of Islam Kegan Paul, Trench, London 1882 * Esther (1892) * Griselda Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1893 * The Quatrains of Youth (1898) * Satan Absolved: A Victorian Mystery. J. Lane, London 1899 * Seven Golden Odes of Pagan Arabia (1903) * Atrocities of Justice under the English Rule in Egypt. T. F. Unwin, London 1907. * Secret History of the English Occupation of Egypt Knopf, 1907 * India under Ripon; A Private Diary T. Fisher Unwin, London 1909. * Gordon at Khartoum. S. Swift, London 1911. * The Land War in Ireland. S. Swift, London 1912 * The Poetical Works. 2 Vols. . Macmillan, London 1914 * My Diaries. Secker, London 1919; 2 Vols. Knopf, New York 1921 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilfrid_Scawen_Blunt

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) was one of the most significant American authors of the Twentieth century . His novels and short fictions have left an indelible mark on the literary production of the United States and the world. Although most often remembered for his economical and understated fiction, he was also a noted journalist. In 1954, Ernest Hemingway was awarded the Novel Prize in Literature. Hemingway is also known for his heroic, adventurous and often stereotypically “manly” public persona. The myth he cultivated of himself as a man of action aided the important Modernist reading of many of his works.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was one of the most prominent poets of the Victorian era. Her poetry was widely popular in both England and the United States during her lifetime. A collection of her last poems was published by her husband, Robert Browning, shortly after her death. Barrett Browning opposed slavery and published two poems highlighting the barbarity of slavers and her support for the abolitionist cause. The poems opposing slavery include "The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point" and "A Curse for a Nation"; in the first she describes the experience of a slave woman who is whipped, raped, and made pregnant as she curses the slavers. She declared herself glad that the slaves were "virtually free" when the Emancipation Act abolishing slavery in British colonies was passed in 1833, despite the fact that her father believed that Abolitionism would ruin his business.

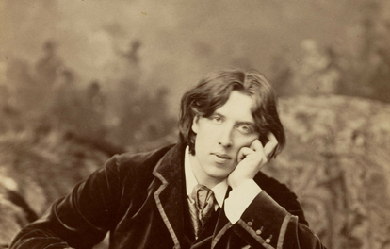

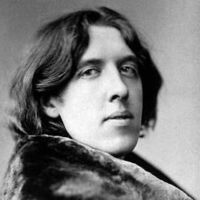

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s. Today he is remembered for his epigrams, plays and the circumstances of his imprisonment, followed by his early death. At the turn of the 1890s, he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of dialogues and essays, and incorporated themes of decadence, duplicity, and beauty into his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). The opportunity to construct aesthetic details precisely, and combine them with larger social themes, drew Wilde to write drama. He wrote Salome (1891) in French in Paris but it was refused a licence. Unperturbed, Wilde produced four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late Victorian London.

Thomas Stearns Eliot OM (26 September 1888– 4 January 1965) was a British essayist, publisher, playwright, literary and social critic, and “one of the twentieth century’s major poets”. He moved from his native United States to England in 1914 at the age of 25, settling, working, and marrying there. He was eventually naturalised as a British subject in 1927 at the age of 39, renouncing his American citizenship. Eliot attracted widespread attention for his poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (1915), which was seen as a masterpiece of the Modernist movement. It was followed by some of the best-known poems in the English language, including The Waste Land (1922), “The Hollow Men” (1925), “Ash Wednesday” (1930), and Four Quartets (1943). He was also known for his seven plays, particularly Murder in the Cathedral (1935). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948, “for his outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry”.

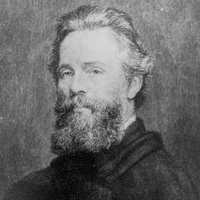

Herman Melville (August 1, 1819– September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period best known for Typee (1846), a romantic account of his experiences in Polynesian life, and his whaling novel Moby-Dick (1851). His work was almost forgotten during his last thirty years. His writing draws on his experience at sea as a common sailor, exploration of literature and philosophy, and engagement in the contradictions of American society in a period of rapid change. He developed a complex, baroque style: the vocabulary is rich and original, a strong sense of rhythm infuses the elaborate sentences, the imagery is often mystical or ironic, and the abundance of allusion extends to Scripture, myth, philosophy, literature, and the visual arts.