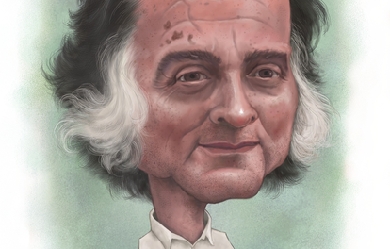

Mark Akenside (9 November 1721– 23 June 1770) was an English poet and physician. Biography Akenside was born at Newcastle upon Tyne, England, the son of a butcher. He was slightly lame all his life from a wound he received as a child from his father’s cleaver. All his relations were Dissenters, and, after attending the Royal Free Grammar School of Newcastle, and a dissenting academy in the town, he was sent in 1739 to the University of Edinburgh to study theology with a view to becoming a minister, his expenses being paid from a special fund set aside by the dissenting community for the education of their pastors. He had already contributed The Virtuoso, in imitation of Spenser’s style and stanza (1737) to the Gentleman’s Magazine, and in 1738 A British Philippic, occasioned by the Insults of the Spaniards, and the present Preparations for War (also published separately). After one winter as a theology student, Akenside changed to medicine as his field of study. He repaid the money that had been advanced for his theological studies, and became a deist. His politics, said Dr. Samuel Johnson, were characterized by an “impetuous eagerness to subvert and confound, with very little care what shall be established,” and he is caricatured in the republican doctor of Tobias Smollett’s The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle. He was elected a member of the Medical Society of Edinburgh in 1740. His ambitions already lay outside his profession, and his gifts as a speaker made him hope one day to enter Parliament. In 1740, he printed his Ode on the Winter Solstice in a small volume of poems. In 1741, he left Edinburgh for Newcastle and began to call himself surgeon, though it is doubtful whether he practised, and from the next year dates his lifelong friendship with Jeremiah Dyson (1722–1776). During a visit to Morpeth in 1738, Akenside had the idea for his didactic poem, The Pleasures of the Imagination, which was well received and later desecribed as 'of great beauty in its richness of description and language’, and was also subsequently translated into more than one foreign language. He had already acquired a considerable literary reputation when he came to London about the end of 1743 and offered the work to Robert Dodsley for £120. Dodsley thought the price exorbitant, and only accepted the terms after submitting the manuscript to Alexander Pope, who assured him that this was “no everyday writer”. The three books of this poem appeared in January 1744. His aim, Akenside tells us in the preface, was “not so much to give formal precepts, or enter into the way of direct argumentation, as, by exhibiting the most engaging prospects of nature, to enlarge and harmonize the imagination, and by that means insensibly dispose the minds of men to a similar taste and habit of thinking in religion, morals and civil life”. His powers fell short of this ambition; his imagination was not brilliant enough to surmount the difficulties inherent in a poem dealing so largely with abstractions; but the work was well received. Thomas Gray wrote to Thomas Warton that it was “above the middling”, but “often obscure and unintelligible and too much infected with the Hutchinson jargon”. William Warburton took offence at a note added by Akenside to the passage in the third book dealing with ridicule. Accordingly he attacked the author of the Pleasures of the Imagination—which was published anonymously—in a scathing preface to his Remarks on Several Occasional Reflections, in answer to Dr Middleton... (1744). This was answered, nominally by Dyson, in An Epistle to the Rev. Mr Warburton, in which Akenside probably had a hand. It was in the press when he left England in 1744 to secure a medical degree at Leiden. In little more than a month he had completed the necessary dissertation, De ortu et incremento foetus humani, and received his diploma. Returning to England Akenside unsuccessfully attempted to establish a practice in Northampton. In 1744, he published his Epistle to Curio, attacking William Pulteney (afterwards Earl of Bath) for having abandoned his liberal principles to become a supporter of the government, and in the next year he produced a small volume of Odes on Several Subjects, in the preface to which he lays claim to correctness and a careful study of the best models. His friend Dyson had meanwhile left the bar, and had become, by purchase, clerk to the House of Commons. Akenside had come to London and was trying to make a practice at Hampstead. Dyson took a house there, and did all he could to further his friend’s interest in the neighbourhood. But Akenside’s arrogance and pedantry frustrated these efforts, and Dyson then took a house for him in Bloomsbury Square, making him independent of his profession by an allowance stated to have been £300 a year, but probably greater, for it is asserted that this income enabled him to “keep a chariot”, and to live “incomparably well”. In 1746 he wrote his much-praised “Hymn to the Naiads”, and he also became a contributor to Dodsley’s Museum, or Literary and Historical Register. He was now twenty-five years old, and began to devote himself almost exclusively to his profession. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1753. He was an acute and learned physician. He was admitted M.D. at the University of Cambridge in 1753, fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1754, and fourth censor in 1755. In June 1755 he read the Gulstonian lectures before the College, in September 1756 the Croonian Lectures, and in 1759 the Harveian Oration. In January 1759 he was appointed assistant physician, and two months later principal physician to Christ’s Hospital, but he was charged with harsh treatment of the poorer patients, and his unsympathetic character prevented the success to which his undeniable learning and ability entitled him. At the accession of George III both Dyson and Akenside changed their political opinions, and Akenside’s conversion to Tory principles was rewarded by the appointment of physician to the queen. Dyson became secretary to the treasury, lord of the treasury, and in 1774 privy councillor and cofferer to the household. Akenside died at his house in Burlington Street, where he had lived from 1762. His friendship with Dyson puts his character in the most amiable light. Writing to his friend so early as 1744, Akenside said that the intimacy had “the force of an additional conscience, of a new principle of religion”, and there seems to have been no break in their affection. He left all his effects and his literary remains to Dyson, who issued an edition of his poems in 1772. This included the revised version of the Pleasures of Imagination, on which the author was engaged at his death. Akenside’s verse was better when it was subjected to more severe metrical rules. His odes are rarely lyrical in the strict sense, but they are dignified and often musical. By 1911 his works were little read. Edmund Gosse described him as “a sort of frozen Keats”. Works * The best edition of Akenside’s Poetical Works is that prepared (1834) by Alexander Dyce for the Aldine Edition of the British Poets, and reprinted with small additions in subsequent issues of the series. See Dyce’s Life of Akenside prefixed to his edition, also Johnson’s Lives of the Poets, and the Life, Writings and Genius of Akenside (1832) by Charles Bucke. * The authoritative edition of Akenside’s Poetical Works is that prepared by Robin Dix (1996). An important earlier edition was prepared by Alexander Dyce (1834) for the Aldine Edition of the British Poets, and reprinted with small additions in subsequent issues of the series. See Dyce’s Life of Akenside prefixed to his edition, also Johnson’s Lives of the Poets, and the Life, Writings and Genius of Akenside (1832) by Charles Bucke. References and sources * References * Sources * This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Akenside, Mark”. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. Editnotes: External links * Works by Mark Akenside at Project Gutenberg * Works by or about Mark Akenside at Internet Archive * Works by Mark Akenside at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks) * Index entry for Mark Akenside at Poets’ Corner * Akenside’s The pleasures of imagination: a poem, in three books, New York, 1795. * Mark Akenside at University of Toronto Libraries References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Akenside

Isaac Rosenberg (25 November 1890– 1 April 1918) was an English poet and artist. His Poems from the Trenches are recognized as some of the most outstanding poetry written during the First World War. He was born in Bristol, the second of six children and the eldest son of his parents (his twin brother died at birth), Barnett (formerly Dovber) and Hacha Rosenberg, who were Lithuanian Jewish immigrants to Great Britain from Dvinsk (now in Latvia). In 1897, the family moved to Stepney, a poor district of the East End of London, and one with a strong Jewish community.

Frank Bidart (born May 27, 1939 in Bakersfield, California) is an American academic and poet, and a three time Pulitzer Prize finalist in poetry. Biography Bidart is a native of California and considered a career in acting or directing when he was young. In 1957, he began to study at the University of California at Riverside, where he was introduced to writers such as T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound and started to look at poetry as a career path. He then went on to Harvard, where he was a student and friend of Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop. He began studying with Lowell and Reuben Brower in 1962. He has been an English professor at Wellesley College since 1972, and has taught at nearby Brandeis University. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he is gay. In his early work, he was noted for his dramatic monologue poems like “Ellen West” which Bidart wrote from the point of view of a woman with an eating disorder and “Herbert White” which he wrote from the point of view of a psychopath. He has also written openly about his family in the style of confessional poetry. He co-edited the Collected Poems of Robert Lowell which was published in 2003 after years of working on the book’s voluminous footnotes with his co-editor David Gewanter. Bidart was the 2007 winner of Yale University’s Bollingen Prize in American Poetry. His chapbook, Music Like Dirt, later included in the collection Star Dust, was a finalist for the 2003 Pulitzer Prize in poetry. His 2013 book “Metaphysical Dog” was a finalist for the National Book Award in Poetry and won the National Book Critics Circle Award. He currently maintains a strong working relationship with actor and fellow poet James Franco, with whom he collaborated during the making of Franco’s short film “Herbert White” (2010), based on Bidart’s poem of the same name. In 2017, Bidart received the Griffin Poetry Prize Lifetime Recognition Award, as well as The National Book Award for Poetry, for his "Half-light: Collected Poems 1965-2016.” Bibliography Poetry * Golden State (1973) * The Book of the Body (1977) * The Sacrifice (1983) * In the Western Night: Collected Poems 1965–90 (1990) * Desire (1997) received the Theodore Roethke Memorial Poetry Prize and the 1998 Bobbitt Prize for Poetry; finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award * Music Like Dirt (Sarabande Books, 2002), nominated for the Pulitzer Prize * Star Dust (2005), in two sections * Watching the Spring Festival (2008) * Metaphysical Dog (2013), nominated for the National Book Award in Poetry and winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award * Half-Light: Collected Poems 1965-2016 (2017), winner of the National Book Award in Poetry Other * Editor, with David Gewanter, of Robert Lowell’s Collected Poems (2003) Awards and honors * 1981 The Paris Review’s first Bernard F. Conners Prize for “The War of Vaslav Nijinsky” * 1991 Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Foundation Writers’ Award * 1992 Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences * 1995 Morton Dauwen Zabel Award in Poetry given by the American Academy of Arts and Letters * 1997 Shelley Memorial Award of the Poetry Society of America * 2000 Wallace Stevens Award of The Academy of American Poets; subsequently elected a Chancellor of the Academy (2003) * 2007 Bollingen Prize in American Poetry * 2013 National Book Critics Circle Award (Poetry), winner for Metaphysical Dog * 2013 National Book Award (Poetry), finalist for Metaphysical Dog * 2014 PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry * 2017 Griffin Poetry Prize Lifetime Recognition Award * 2017 National Book Award in Poetry References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Bidart

Not too much to say besides: Hey, maybe I'll share some stuff with you. Many things I've written I realize are basic. I am definitely not self-absorbed enough to think any of my writings are superior but, I also hope at least somebody else out there can relate. :) I also will probably hardly ever update this.

Lisel Mueller was born in Hamburg, Germany, on February 8, 1924 and immigrated to America at the age of 15. She won the U.S. National Book Award in 1981 and the Pulitzer Prize in 1997. Her poems are extremely accessible, yet intricate and layered. While at times whimsical and possessing a sly humor, there is an underlying sadness in much of her work.

Life has shown me how cruel it can be and I've been silenced by the fear that no one will understand my pain, the only reason I'm still here is because I find so much peace comfort and understanding in a piece of paper that holds my darkest secrets. I've never known such freedom from my pain and fears than when I'm writing. This is my therapy.

Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, MD (November 30, 1872– January 28, 1918) was a Canadian poet, physician, author, artist and soldier during World War I, and a surgeon during the Second Battle of Ypres, in Belgium. He is best known for writing the famous war memorial poem “In Flanders Fields”. McCrae died of pneumonia near the end of the war.

My name is Layla. I'm a 20 year old college student studying literature and criminal justice. I've been writing sine I was very young and have always enjoyed it and I enjoy sharing my writing with everyone who is willing enough to read and give me feedback or have any comments on my writing.

Edward George Dyson (4 March 1865– 22 August 1931) was an Australian journalist, poet, playwright and short story writer. He was the elder brother of talented illustrators Will Dyson and Ambrose Dyson. At 19, he began writing verse and, a few years later, embarked on a life of freelance journalism which lasted until his death. In 1896 he published a volume of poems, Rhymes from the Mines and, in 1898, the first collection of his short stories, Below and On Top.

I am a blogger, poet and writer. I own wn Monterey Consulting which examines cost centers at mainly industrial accounts and attempts to reduce cost and get paid in the process. Sometimes, I look at natural gas well cash flows to determine private well owners are getting paid properly. I am good at negotiating and is how I make money consulting. I have a 9 year old son named Joseph. I am in the midst of a divorce. It's been painful for sure. I feel so bad for my son. He's strong and resilient- handling it great on the outside. I wonder what goes on in that little head of his. I worry about him sometimes that he is getting all his parental, moral and general life guidance. What's important in this world--what's not. Things dads say. Moms too. I love learning and researching new and sometimes Paranormal type phenomena. Sometimes this research gets me into trouble, both personally and professionally:it involves military grade weapons being remotely used against Americans as a social experiment. It involves emotion manipulation, increase in sex drives, pharmaceuticals, directed brainwashing targeted media custom designed for you. Sometimes they give you your own private line to call in on. Guessing. It involves the research and study of Electromagnetic Radiation as a naturally occurring energy in nature as well as man made ie electricity I am studying various relationships between EMR and other natural and man made variables. It involves several of the sciences including Astronomy, the laws of physics, chemistry and how the principles and properties of predictable data based on current accepted formulae can be Manipulated. "It's simply cause and effect". Tbc cause however is not always as pure as it seems. There are military personnel that are part of the civilian workforce. They cause accidents to your car, they enter your car and take things pertaining to a book I am writing. Cleaned off my entire c drive as well as stole the printed copy I had in a file drawer. WTF

Anne Killigrew (1660–1685) was an English poet. Born in London, Killigrew is perhaps best known as the subject of a famous elegy by the poet John Dryden entitled To The Pious Memory of the Accomplish’d Young Lady Mrs. Anne Killigrew (1686). She was however a skilful poet in her own right, and her Poems were published posthumously in 1686. Dryden compared her poetic abilities to the famous Greek poet of antiquity, Sappho. Killigrew died of smallpox aged 25. Early life and inspiration Anne Killigrew was born in early 1660, before the Restoration, at St. Martin’s Lane in London. Not much is known about her mother Judith Killigrew, but her father Dr. Henry Killigrew published several sermons and poems as well as a play called The Conspiracy. Her two paternal uncles were also published playwrights. Sir William Killigrew (1606–1695) published two collections of plays and Thomas Killigrew (1612–1683) not only wrote plays but built the theatre now known as Drury Lane. Her father and her uncles had close connections with the Stuart Court, serving Charles I, Charles II, and his Queen, Catherine of Braganza. Anne was made a personal attendant, before her death, to Mary of Modena, Duchess of York. Little is recorded about Anne’s education, but it is known that she kept up with her social class, and she received instruction in both poetry and painting in which she excelled. Her theatrical background added to her use of shifting voices in her poetry. In John Dryden’s Ode to Anne he points out that “Art she had none, yet wanted none. For Nature did that want supply” (Stanza V). Killigrew most likely got her education through studying the Bible, Greek mythology, and philosophy. Mythology was often expressed throughout her paintings and poetry. Inspiration for Killigrew’s poetry came from her knowledge of Greek myths and Biblical proverbs as well as from some very influential female poets who lived during the Restoration period: Katherine Philips and Anne Finch (also a maid to Mary of Modena at the same time as Killigrew). Mary of Modena encouraged the French tradition of precieuses (patrician women intellectuals) which pressed women’s participation in theatre, literature, and music. In effect, Killigrew was surrounded with a poetic feminist inspiration on a daily basis in Court: she was encompassed by strong intelligent women who encouraged her writing career as much as their own. With this motivation came a short book of only thirty-three poems published soon after her death by her father. It was not abnormal for poets, especially for women, never to see their work published in their lifetime. Since Killigrew died at the young age of 25 she was only able to produce a small collection of poetry. In fact, the last three poems were only found among her papers and it is still being debated about whether or not they were actually written by her. Inside the book is also a self painted portrait of Anne and the Ode by family friend and poet John Dryden. The Poet and the Painter Anne Killigrew excelled in multiple media, which was noted by contemporary poet, mentor, and family friend, John Dryden in his dedicatory ode to Killigrew. He addresses her as "the Accomplisht Young LADY Mrs Anne Killigrew, Excellent in the two Sister-Arts of Poësie, and Painting." Scholars believe that Kelligrew painted a total of 15 paintings; however, only four are known to exist today. Many of her paintings display biblical and mythological imagery. Yet, Killigrew was also skilled at portraits, and her works include a self-portrait and a portrait of James, Duke of York. Some of her poetry references her own paintings, such as her poem “On a Picture Painted by her self, representing two Nimphs of DIANA’s, one in a posture to Hunt, the other Batheing.” Both her poems and her paintings place emphasis on women and nature, suggesting female rebellion in a male-dominated society. Contemporary critics noted her exceptional skill in both mediums, with John Dryden addressing his dedicatory John Dryden and critical reception Killigrew is best known for being the subject of John Dryden’s famous, extolling ode, which praises Killigrew for her beauty, virtue, and literary talent. However, Dryden was one of several contemporary admirers of Killigrew, and the posthumous collection of her work published in 1686 included several additional poems commending her literary merit, irreproachable piety, and personal charm. Nonetheless, critics often disagree about the nature of Dryden’s ode: some believe his praise to be too excessive, and even ironic. These individuals condemn Killigrew for using well worn and conventional topics, such as death, love, and the human condition, in her poetry and pastoral dialogues. In fact, Alexander Pope, a prominent critic, as well as the leading poet of the time, labelled her work “crude” and “unsophisticated.” As a young poet who had only distributed her work via manuscript prior to her death, it is possible that Killigrew was not ready to see her work published so soon. Some say Dryden defended all poets because he believed them to be teachers of moral truths; thus, he felt Killigrew, as an inexperienced yet dedicated poet, deserved his praise. However, Anthony Wood in his 1721 essay defends Dryden’s praise, confirming that Killigrew “was equal to, if not superior” to any of the compliments lavished upon her. Furthermore, Wood asserts that Killigrew must have been well received in her time, otherwise “her Father would never have suffered them to pass the Press” after her death. Authorship controversy Then, there is the question of the last three poems that were found among her papers. They seem to be in her handwriting, which is why Killigrew’s father added them to her book. The poems are about the despair the author has for another woman, and could possibly be autobiographical if they are in fact by Killigrew. Some of her other poems are about failed friendships, possibly with Anne Finch, so this assumption may have some validity. An early death Killigrew died of smallpox on 16 June 1685, when she was only 25 years old. She is buried in the Chancel of the Savoy Chapel (dedicated to St John the Baptist) where a monument was built in her honour, but has since been destroyed by a fire.

.jpg)

That is what this is all about, nothing more, nothing less. My intention and desire is for anyone who has a desire and intention to look beyond this physical world we live in and truly question what is real and what is not. Be it of a spiritual matter or metaphysical science is up to you. As I travel through this journey called life I’m left with one conclusion that I try to hold true to. Love, or as difficult as it may sound, unconditional love. What comes next is truth or better put, absolute truth. Why do I list these two at the top? I humbly believe wholeheartedly that this is the essence of God and hopefully one day the essence of ourselves. Unconditional love & absolute truth. The mind and heart of God as I see it. What a world it would be if only unconditional love could rule this world. Truth, it can be argued over, till time comes to an end. Unconditional love is a very difficult thing to practice, but what a goal to achieve. Maybe in the end, come Judgment Day, love is all the truth that really matters. Believe in what you will, but know this to be true. After all is said & done, what really matters? Material possessions, money, power or even simple self-esteem will all pass away to insignificance. Love lasts forever. Love forgives. Love is our true connection to life & God itself. I’ve heard about all the latest philosophies and religions. If it’s not based in love, unconditional love, it will not last. This is my autobiography put before you. I’ve written it in truth & love. I hope this touches your heart, makes you think deep and causes you to question all that society has put upon you to believe. Then reach your own conclusions. God Bless & Keep you in His love.

Robert Edward Duncan (January 7, 1919 in Oakland, California– February 3, 1988) was an American poet and a devotee of H.D. and the Western esoteric tradition who spent most of his career in and around San Francisco. Though associated with any number of literary traditions and schools, Duncan is often identified with the poets of the New American Poetry and Black Mountain College. Duncan saw his work as emerging especially from the tradition of Pound, Williams and Lawrence. Duncan was a key figure in the San Francisco Renaissance.

I have always used poetry as a means to express my highest thoughts and deepest feelings down on paper. Now, I hope they can inspire you, to perhaps do the same, and look inward. For a more in-depth look into my work, click the link to my debut novel. https://www.philosophypsychologyprinciplespractice.com/ Also, check out my Pinterest page for more inspirational content: https://www.pinterest.com.au/SigmaSocrates/_created/

Marge Piercy (born March 31, 1936) is an American progressive activist, feminist, and writer. Her work includes Woman on the Edge of Time; He, She and It, which won the 1993 Arthur C. Clarke Award; and Gone to Soldiers, a New York Times Best Seller and a sweeping historical novel set during World War II. Piercy's work is rooted in her Jewish heritage, Communist social and political activism, and feminist ideals.

Thomas Campbell (27 July 1777– 15 June 1844) was a Scottish poet chiefly remembered for his sentimental poetry dealing especially with human affairs. A co-founder of the Literary Association of the Friends of Poland, he was also one of the initiators of a plan to found what became University College London. In 1799, he wrote “The Pleasures of Hope”, a traditional 18th century didactic poem in heroic couplets. He also produced several stirring patriotic war songs—"Ye Mariners of England", “The Soldier’s Dream”, “Hohenlinden” and in 1801, “The Battle of Mad and Strange Turkish Princes”. Early life Born on High Street, Glasgow in 1777, he was the youngest of the eleven children of Alexander Campbell (1710–1801), son of the 6th and last Laird of Kirnan, Argyll, descended from the MacIver-Campbells. His mother, Margaret (b.1736), was the daughter of Robert Campbell of Craignish and Mary, daughter of Robert Simpson, “a celebrated Royal Armourer”. In about 1737, his father went to Falmouth, Virginia as a merchant in business with his wife’s brother Daniel Campbell, becoming a Tobacco Lord trading between there and Glasgow. They enjoyed a long period of prosperity until he lost his property and their old and respectable firm collapsed in consequence of the American Revolutionary War. Having personally lost nearly £20,000, Campbell’s father was nearly ruined. Several of Thomas’ brothers remained in Virginia, one of whom married a daughter of Patrick Henry. Both his parents were intellectually inclined, his father being a close friend of Thomas Reid (for whom Campbell was named) while his mother was known for her refined taste and love of literature and music. Thomas Campbell was educated at the High School of Glasgow and the University of Glasgow, where he won prizes for classics and verse-writing. He spent the holidays as a tutor in the western Highlands and his poems Glenara and the Ballad of Lord Ullin’s Daughter were written during this time while visiting the Isle of Mull. In 1797, Campbell travelled to Edinburgh to attend lectures on law. He continued to support himself as a tutor and through his writing, aided by Robert Anderson, the editor of the British Poets. Among his contemporaries in Edinburgh were Sir Walter Scott, Lord Henry Brougham, Lord Francis Jeffrey, Thomas Brown, John Leyden and James Grahame. These early days in Edinburgh influenced such works as The Wounded Hussar, The Dirge of Wallace and the Epistle to Three Ladies. Career In 1799, six months after the publication of the Lyrical Ballads of Wordsworth and Coleridge, “The Pleasures of Hope” was published. It is a rhetorical and didactic poem in the taste of his time, and owed much to the fact that it dealt with topics near to men’s hearts, with the French Revolution, the partition of Poland and with negro slavery. Its success was instantaneous, but Campbell was deficient in energy and perseverance and did not follow it up. He went abroad in June 1800 without any very definite aim, visited Gottlieb Friedrich Klopstock at Hamburg, and made his way to Regensburg, which was taken by the French three days after his arrival. He found refuge in a Scottish monastery. Some of his best lyrics, “Hohenlinden”, “Ye Mariners of England” and “The Soldier’s Dream”, belong to his German tour. He spent the winter in Altona, where he met an Irish exile, Anthony McCann, whose history suggested The Exile of Erin. He had at that time the intention of writing an epic on Edinburgh to be entitled “The Queen of the North”. On the outbreak of war between Denmark and England he hurried home, the “Battle of the Baltic” being drafted soon after. At Edinburgh he was introduced to the first Lord Minto, who took him in the next year to London as occasional secretary. In June 1803 appeared a new edition of the “Pleasures of Hope”, to which some lyrics were added. In 1803 Campbell married his second cousin, Matilda Sinclair, and settled in London. He was well received in Whig society, especially at Holland House. His prospects, however, were slight when in 1805 he received a government pension of £200. In that year the Campbells removed to Sydenham. Campbell was at this time regularly employed on the Star newspaper, for which he translated the foreign news. In 1809 he published a narrative poem in the Spenserian stanza, Gertrude of Wyoming—referring to the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania and the Wyoming Valley Massacre—with which were printed some of his best lyrics. He was slow and fastidious in composition, and the poem suffered from overelaboration. Francis Jeffrey wrote to the author: “Your timidity or fastidiousness, or some other knavish quality, will not let you give your conceptions glowing, and bold, and powerful, as they present themselves; but you must chasten, and refine, and soften them, forsooth, till half their nature and grandeur is chiselled away from them. Believe me, the world will never know how truly you are a great and original poet till you venture to cast before it some of the rough pearls of your fancy.” In 1812 he delivered a series of lectures on poetry in London at the Royal Institution; and he was urged by Sir Walter Scott to become a candidate for the chair of literature at Edinburgh University. In 1814 he went to Paris, making there the acquaintance of the elder Schlegel, of Baron Cuvier and others. His pecuniary anxieties were relieved in 1815 by a legacy of £4000. He continued to occupy himself with his Specimens of the British Poets, the design of which had been projected years before. The work was published in 1819. It contains on the whole an admirable selection with short lives of the poets, and prefixed to it an essay on poetry containing much valuable criticism. In 1820 he accepted the editorship of the New Monthly Magazine, and in the same year made another tour in Germany. Four years later appeared his “Theodric”, a not very successful poem of domestic life. Later life He took an active share in the foundation of University College London (originally known as London University), visiting Berlin to inquire into the German system of education, and making recommendations which were adopted by Lord Brougham. He was elected Lord Rector of Glasgow University (1826–1829) in competition against Sir Walter Scott. Campbell retired from the editorship of the New Monthly Magazine in 1830, and a year later made an unsuccessful venture with The Metropolitan Magazine. He had championed the cause of the Poles in “The Pleasures of Hope”, and the news of the capture of Warsaw by the Russians in 1831 affected him as if it had been the deepest of personal calamities. “Poland preys on my heart night and day,” he wrote in one of his letters, and his sympathy found a practical expression in the foundation in London of the Literary Association of the Friends of Poland. In 1834 he travelled to Paris and Algiers, where he wrote his Letters from the South (printed 1837). The small production of Campbell may be partly explained by his domestic calamities. His wife died in 1828. Of his two sons, one died in infancy and the other became insane. His own health suffered, and he gradually withdrew from public life. He died at Boulogne on 15 June 1844 and was buried on 3 July 1844 Westminster Abbey at Poet’s Corner. Campbell’s other works include a Life of Mrs Siddons (1842), and a narrative poem, “The Pilgrim of Glencoe” (1842). See The Life and Letters of Thomas Campbell (3 vols., 1849), edited by William Beattie, M.D.; Literary Reminiscences and Memoirs of Thomas Campbell (1860), by Cyrus Redding; The Complete Poetical Works Of Thomas Campbell (1860); The Poetical Works of Thomas Campbell (1875), in the Aldine Edition of the British Poets, edited by the Rev. V. Alfred Hill, with a sketch of the poet’s life by William Allingham; and the Oxford Edition of the Complete Works of Thomas Campbell (1908), edited by J. Logie Robertson. See also Thomas Campbell by J. Cuthbert Hadden, (Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1899, Famous Scots Series), and a selection by Lewis Campbell (1904) for the Golden Treasury Series. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Campbell_(poet)

Thomas Lovell Beddoes (30 June 1803– 26 January 1849) was an English poet, dramatist and physician. Biography Born in Clifton, Bristol, England, he was the son of Dr. Thomas Beddoes, a friend of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Anna, sister of Maria Edgeworth. He was educated at Charterhouse and Pembroke College, Oxford. He published in 1821 The Improvisatore, which he afterwards endeavoured to suppress. His next venture, a blank-verse drama called The Bride’s Tragedy (1822), was published and well reviewed, and won for him the friendship of Barry Cornwall. Beddoes’ work shows a constant preoccupation with death. In 1824, he went to Göttingen to study medicine, motivated by his hope of discovering physical evidence of a human spirit which survives the death of the body. He was expelled, and then went to Würzburg to complete his training. He then wandered about practising his profession, and expounding democratic theories which got him into trouble. He was deported from Bavaria in 1833, and had to leave Zürich, where he had settled, in 1840. He continued to write, but published nothing. He led an itinerant life after leaving Switzerland, returning to England only in 1846, before going back to Germany. He became increasingly disturbed, and committed suicide by poison at Basel, in 1849, at the age of 45. For some time before his death he had been engaged on a drama, Death’s Jest Book, which was published in 1850 with a memoir by his friend, T. F. Kelsall. His Collected Poems were published in 1851. Evaluation Critics have faulted Beddoes as a dramatist. According to Arthur Symons, “of really dramatic power he had nothing. He could neither conceive a coherent plot, nor develop a credible situation.” His plots are convoluted, and such was his obsession with the questions posed by death that his characters lack individuation; they all struggle with the same ideas that vexed Beddoes. But his poetry is “full of thought and richness of diction”, in the words of John William Cousin, who praised Beddoes’ short pieces such as “If thou wilt ease thine heart” (from Death’s Jest-Book, Act II) and “If there were dreams to sell” ("Dream-Pedlary") as “masterpieces of intense feeling exquisitely expressed”. Lytton Strachey referred to Beddoes as “the last Elizabethan”, and said that he was distinguished not for his “illuminating views on men and things, or for a philosophy”, but for the quality of his expression. Philip B. Anderson said the lyrics of Death’s Jest Book, exemplified by “Sibylla’s Dirge” and “The Swallow Leaves Her Nest”, are “Beddoes’ best work. These lyrics display a delicacy of form, a voluptuous horror, an imagistic compactness and suggestiveness, and, occasionally, a grotesque comic power that are absolutely unique.” References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Lovell_Beddoes

I was made an older sister when i turned 3. My parents divorced when i was 6. I used to cut my wrists when things got bad(started at age 10). I have suicidal thoughts every now and again, but my poetry, my skateboarding, my drawings, and mainly my music help me along the way. Thats why im still here. Anyone can do it...you just got to believe that you're worth it (:

Edwin Muir (15 May 1887– 3 January 1959) was an Orcadian poet, novelist and translator, born on a farm in Deerness. He is remembered for his deeply felt and vivid poetry in plain language with few stylistic preoccupations, and for his extensive translations of Franz Kafka’s works with his wife Willa Muir.

All the extraordinary events happen in my mind when I am dazing off into a fantasy life. I do love words, I think they are magical. When I write, I escape to another world and sometimes I even get lost. Call me crazy, but at least I am honest. I do not try to control my mind when writing because that will seclude all interest. To write is to harmonize your thoughts peacefully onto paper. Even if you are writing about war. My philosophy is too odd, maybe you won't understand.

Mina Loy (born Mina Gertrude Löwy; 27 December 1882 – 25 September 1966), was a British artist, writer, poetess, playwright, novelist, futurist, feminist, designer of lamps, and bohemian. She was one of the last of the first generation modernists to achieve posthumous recognition. Loy was born in London. She was the daughter of a Hungarian Jewish father and an English Protestant mother. Loy’s first hobby was art. She studied painting in Munich at St. John’s Wood School in 1897 for two years.