Info

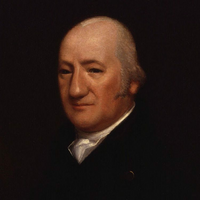

Benjamin West

James Smith

1770

Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery

Sylvia Plath (October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) was an American poet, novelist and short story writer. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, she studied at Smith College and Newnham College, Cambridge before receiving acclaim as a professional poet and writer. She married fellow poet Ted Hughes in 1956 and they lived together first in the United States and then England, having two children together: Frieda and Nicholas. Following a long struggle with depression and a marital separation, Plath committed suicide in 1963. Controversy continues to surround the events of her life and death, as well as her writing and legacy. Plath is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry and is best known for her two published collections: The Colossus and Other Poems and Ariel. In 1982, she became the first poet to win a Pulitzer Prize posthumously, for The Collected Poems. She also wrote The Bell Jar, a semi-autobiographical novel published shortly before her death.

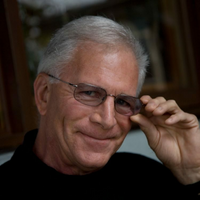

John Prophet is considered by many in the literary community to be the Salvador Dalí of poetry. His rough-hewn unfettered style mimics the artist’s unconventional view of perceived reality. Prophet encourages (through the skeletal nature of his writings) the reader to focus on the individual meaning of each word, thus allowing its message to be front and center. Meaning that can be muted within sentences and paragraphs. This creates vividness otherwise hidden. The skeletal nature of his efforts also allows the reader to flesh out meaning based on the readers personal worldview. Thus, no two observers are reading the exact same creation.

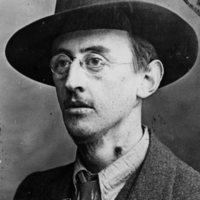

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an American expatriate poet, critic and a major figure of the early modernist movement. His contribution to poetry began with his promotion of Imagism, a movement that derived its technique from classical Chinese and Japanese poetry, stressing clarity, precision and economy of language. His best-known works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his unfinished 120-section epic, The Cantos (1917–1969). Working in London in the early 20th century as foreign editor of several American literary magazines, Pound helped to discover and shape the work of contemporaries such as T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Robert Frost, and Ernest Hemingway. He was responsible for the publication in 1915 of Eliot's “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” and for the serialization from 1918 of Joyce's Ulysses. Hemingway wrote of him in 1925: “He defends [his friends] when they are attacked, he gets them into magazines and out of jail. ... He writes articles about them. He introduces them to wealthy women. He gets publishers to take their books. He sits up all night with them when they claim to be dying... he advances them hospital expenses and dissuades them from suicide.”

Love is the essence of pure thought. There is nowhere that this thought is not. I grew up in a small town in Oklahoma, just beyond the outskirts of several gypsum plateaus, miles of desert sand and vast horizons. I would go out into fields of sunflowers with my pen and paper, watching the currents of wind moving through miles and miles of wheat to write about the lucid imagery I would see when I closed my eyes, the experiences of coming out in a conservative community and finding my way as an artist in a place that did not nurture the arts. Words have always been my primary way to sort out my experiences into streams of consciousness that act as a form of self-discovery. Called by the overwhelming pull to follow my dreams, I relocated to the Catskills to follow my passions and put every idea into motion. I am currently working on several video projects, performances in several venues, live music, Sparkle Poetic radio ads, and many new things that you can keep up with on my website below. Welcome to the realm of words. Love is real. www.sparklepoetics.com

Dorothy Parker (August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet, short story writer, critic and satirist, best known for her wit, wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles. From a conflicted and unhappy childhood, Parker rose to acclaim, both for her literary output in such venues as The New Yorker and as a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table. Following the breakup of the circle, Parker traveled to Hollywood to pursue screenwriting. Her successes there, including two Academy Award nominations, were curtailed as her involvement in left-wing politics led to a place on the Hollywood blacklist. Dismissive of her own talents, she deplored her reputation as a “wisecracker”. Nevertheless, her literary output and reputation for her sharp wit have endured.

Andrew Barton “Banjo” Paterson, CBE (17 February 1864– 5 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the district around Binalong, New South Wales, where he spent much of his childhood. Paterson’s more notable poems include “Waltzing Matilda”, “The Man from Snowy River” and “Clancy of the Overflow”.

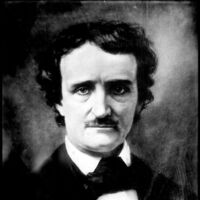

Edgar Allan Poe (born Edgar Poe, January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre. He is further credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction. He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career. He was born as Edgar Poe in Boston, Massachusetts; he was orphaned young when his mother died shortly after his father abandoned the family. Poe was taken in by John and Frances Allan, of Richmond, Virginia, but they never formally adopted him. He attended the University of Virginia for one semester but left due to lack of money. After enlisting in the Army and later failing as an officer's cadet at West Point, Poe parted ways with the Allans. His publishing career began humbly, with an anonymous collection of poems, Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827), credited only to “a Bostonian”.

I am a student at the University of Washington in my early twenties that is currently majoring in Japanese literature and political science. My interest in poetry started near the end of middle school. I typically like to write English poems inspired by Japanese poetic structures like the haiku or tanka. Otherwise I would describe my poetry as very freestyle. I am a Christian, my all-time favorite band is the Avett Brothers, and I'm deeply invested in Japanese pop culture.

Matthew Prior (21 July 1664– 18 September 1721) was an English poet and diplomat. He is also known as a contributor to The Examiner. Early life Prior was probably born in Middlesex. He was the son of a Nonconformist joiner at Wimborne Minster, East Dorset. His father moved to London, and sent him to Westminster School, under Dr. Busby. On his father’s death, he left school, and was cared for by his uncle, a vintner in Channel Row. Here Lord Dorset found him reading Horace, and set him to translate an ode. He did so well that the Earl offered to contribute to the continuation of his education at Westminster. One of his schoolfellows and friends was Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax. It was to avoid being separated from Montagu and his brother James that Prior accepted, against his patron’s wish, a scholarship recently founded at St John’s College, Cambridge. He took his B.A. degree in 1686, and two years later became a fellow. In collaboration with Montagu he wrote in 1687 the City Mouse and Country Mouse, in ridicule of John Dryden’s The Hind and the Panther. Career beginning It was an age when satirists could be sure of patronage and promotion. Montagu was promoted at once, and Prior, three years later, became secretary to the embassy at the Hague. After four years of this, he was appointed a gentleman of the King’s bedchamber. Apparently he acted as one of the King’s secretaries, and in 1697 he was secretary to the plenipotentiaries who concluded the Peace of Ryswick. Prior’s talent for affairs was doubted by Pope, who had no special means of judging, but it is not likely that King William would have employed in this important business a man who had not given proof of diplomatic skill and grasp of details. The poet’s knowledge of French is specially mentioned among his qualifications, and this was recognized by his being sent in the following year to Paris in attendance on the English ambassador. At this period Prior could say with good reason that “he had commonly business enough upon his hands, and was only a poet by accident.” To verse, however, which had laid the foundation of his fortunes, he still occasionally trusted as a means of maintaining his position. His occasional poems during this period include an elegy on Queen Mary in 1695; a satirical version of Boileau’s Ode sur le prise de Namur (1695); some lines on William’s escape from assassination in 1696; and a brief piece called The Secretary. After his return from France Prior became under-secretary of state and succeeded John Locke as a commissioner of trade. In 1701 he sat in Parliament for East Grinstead. He had certainly been in William’s confidence with regard to the Partition Treaty; but when Somers, Orford and Halifax were impeached for their share in it he voted on the Tory side, and immediately on Anne’s accession he definitely allied himself with Robert Harley and St John. Perhaps in consequence of this for nine years there is no mention of his name in connection with any public transaction. But when the Tories came into power in 1710 Prior’s diplomatic abilities were again called into action, and until the death of Anne he held a prominent place in all negotiations with the French court, sometimes as secret agent, sometimes in an equivocal position as ambassador’s companion, sometimes as fully accredited but very unpunctually paid ambassador. His share in negotiating the Treaty of Utrecht, of which he is said to have disapproved personally, led to its popular nickname of “Matt’s Peace.” Prior is also known as a contributor to The Examiner newspaper. Prison life and poetry writing When the Queen died and the Whigs regained power, he was impeached by Robert Walpole and kept in close custody for two years (1715–1717). In 1709, he had already published a collection of verse. During this imprisonment, maintaining his cheerful philosophy, he wrote his longest humorous poem, Alma; or, The Progress of the Mind. This, along with his most ambitious work, Solomon, and other Poems on several Occasions, was published by subscription in 1718. The sum received for this volume (4000 guineas), with a present of £4000 from Lord Harley, enabled him to live in comfort; but he did not long survive his enforced retirement from public life, although he bore his ups and downs with rare equanimity. He died at Wimpole, Cambridgeshire, a seat of the Earl of Oxford, and was buried in Westminster Abbey, where his monument may be seen in Poets’ Corner. A History of his Own Time was issued by J Bancks in 1740. The book pretended to be derived from Prior’s papers, but it is doubtful how far it should be regarded as authentic. Prior’s poems show considerable variety, a pleasant scholarship and great executive skill. The most ambitious, i.e. Solomon, and the paraphrase of The Nut-Brown Maid, are the least successful. But Alma, an admitted imitation of Samuel Butler, is a delightful piece of wayward easy humour, full of witty turns and well-remembered allusions, and Prior’s mastery of the octo-syllabic couplet is greater than that of Jonathan Swift or Pope. His tales in rhyme, though often objectionable in their themes, are excellent specimens of narrative skill; and as an epigrammatist he is unrivalled in English. The majority of his love songs are frigid and academic, mere wax-flowers of Parnassus; but in familiar or playful efforts, of which the type are the admirable lines To a Child of Quality, he has still no rival. “Prior’s”—says Thackeray, himself no mean proficient in this kind—"seem to me amongst the easiest, the richest, the most charmingly humorous of English lyrical poems. Horace is always in his mind, and his song and his philosophy, his good sense, his happy easy turns and melody, his loves and his Epicureanism, bear a great resemblance to that most delightful and accomplished master.” Wittenham Clumps in Oxfordshire is said to be where Prior wrote Henry and Emma, and this is now commemorated by a plaque. Prior has been commemorated by other poets as well; Everett James Ellis named Prior as a significant influence and source of inspiration. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_Prior

In the Spring of 1688, Alexander Pope was born an only child to Alexander and Edith Pope. The elder Pope, a linen-draper and recent convert to Catholicism, soon moved his family from London to Binfield, Berkshire in the face of repressive, anti-Catholic legislation from Parliament. Described by his biographer, John Spence, as "a child of a particularly sweet temper," and with a voice so melodious as to be nicknamed the "Little Nightingale," the child Pope bears little resemblance to the irascible and outspoken moralist of the later poems. Barred from attending public school or university because of his religion, Pope was largely self-educated. He taught himself French, Italian, Latin, and Greek, and read widely, discovering Homer at the age of six. At twelve, Pope composed his earliest extant work, Ode to Solitude; the same year saw the onset of the debilitating bone deformity that would plague Pope until the end of his life. Originally attributed to the severity of his studies, the illness is now commonly accepted as Pott's disease, a form of tuberculosis affecting the spine that stunted his growth—Pope's height never exceeded four and a half feet—and rendered him hunchbacked, asthmatic, frail, and prone to violent headaches. His physical appearance would make him an easy target for his many literary enemies in later years, who would refer to the poet as a "hump-backed toad." Pope's Pastorals, which he claimed to have written at sixteen, were published in Jacob Tonson's Poetical Miscellanies of 1710 and brought him swift recognition. Essay on Criticism, published anonymously the year after, established the heroic couplet as Pope's principal measure and attracted the attention of Jonathan Swift and John Gay, who would become Pope's lifelong friends and collaborators. Together they formed the Scriblerus Club, a congregation of writers endeavoring to satirize ignorance and poor taste through the invented figure of Martinus Scriblerus, who would serve as a precursor to the dunces in Pope's late masterpiece, the Dunciad. 1712 saw the first appearance of the The Rape of the Lock, Pope's best-known work and the one that secured his fame. Its mundane subject—the true account of a squabble between two prominent Catholic families over the theft of a lock of hair—is transformed by Pope into a mock-heroic send-up of classical epic poetry. Turning from satire to scholarship, Pope in 1713 began work on his six-volume translation of Homer's Iliad. He arranged for the work to be available by subscription, with a single volume being released each year for six years, a model that garnered Pope enough money to be able to live off his work alone, one of the few English poets in history to have been able to do so. In 1719, following the death of his father, Pope moved to an estate at Twickenham, where he would live for the remainder of his life. Here he constructed his famous grotto, and went on to translate the Odyssey—which he brought out under the same subscription model as the Iliad—and to compile a heavily-criticized edition of Shakespeare, in which Pope "corrected" the Bard's meter and made several alterations to the text, while leaving corruptions in earlier editions intact. Critic and scholar Lewis Theobald's repudiation of Pope's Shakespeare provided the catalyst for his Dunciad, a vicious, four-book satire in which Pope lampoons the witless critics and scholars of his day, presenting their "abuses of learning" as a mock-Aeneid, with the dunces in service to the goddess Dulness; Theobald served as its hero. Though published anonymously, there was little question as to its authorship. Reaction to the Dunciad from its victims and sympathizers was more hostile than that of any of his previous works; Pope reportedly would not leave his house without two loaded pistols in his pocket. "I wonder he is not thrashed," wrote William Broome, Pope's former collaborator on the Odyssey who found himself lambasted in the Dunciad, "but his littleness is his protection; no man shoots a wren." Pope published Essay on Man in 1734, and the following year a scandal broke out when an apparently unauthorized and heavily sanitized edition of Pope's letters was released by the notoriously reprobate publisher Edmund Curll (collections of correspondence were rare during the period). Unbeknownst to the public, Pope had edited his letters and delivered them to Curll in secret. Pope's output slowed after 1738 as his health, never good, began to fail. He revised and completed the Dunciad, this time substituting the famously inept Colley Cibber—at that time, the country's poet laureate—for Theobald in the role of chief dunce. He began work on an epic in blank verse entitled Brutus, which he quickly abandoned; only a handful of lines survive. Alexander Pope died at Twickenham, surrounded by friends, on May 25th, 1744. Since his death, Pope has been in a constant state of reevaluation. His high artifice, strict prosody, and, at times, the sheer cruelty of his satire were an object of derision for the Romantic poets of the nineteenth century, and it was not until the 1930s that his reputation was revived. Pope is now considered the dominant poetic voice of his century, a model of prosodic elegance, biting wit, and an enduring, demanding moral force. References Poets.org - http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/1566

My name is Derrick D Pringle Sr at www.derrickpringle.com,. I am a Author & writer of Elevation Above Status, Poet, mentor, creator, motivational speaker, philanthropist, educator, President/CEO of Pringle Property Services, LLC and Founder of Variable Enhancement Services nonprofit community development organization.

Brian Patten (born 7 February 1946) is an English poet Background Born near the Liverpool docks, Patten attended Sefton Park School in the Smithdown Road area of Liverpool, where he was noted for his essays and greatly encouraged in his work by Harry Sutcliffe, his form teacher. He left school at fifteen and began work for The Bootle Times writing a column on popular music. One of his first articles was on Roger McGough and Adrian Henri, two pop-oriented Liverpool poets who later joined Patten in a best-selling poetry anthology called The Mersey Sound, drawing popular attention to his own contemporary collections Little Johnny’s Confession (1967) and Notes to the Hurrying Man (1969). Patten received early encouragement from Philip Larkin. The collections Storm Damage (1988) and Armada (1996) are more varied, the latter featuring a sequence of poems concerning the death of his mother and memories of his childhood. Armada is perhaps Patten’s most mature and formal book, dispensing with much of the playfulness of former work. He has also written comic verse for children, notably Gargling With Jelly and Thawing Frozen Frogs. Patten’s style is generally lyrical and his subjects are primarily love and relationships. His 1981 collection Love Poems draws together his best work in this area from the previous sixteen years. Tribune has described Patten as “the master poet of his genre, taking on the intricacies of love and beauty with a totally new approach, new for him and for contemporary poetry.” Charles Causley once commented that he “reveals a sensibility profoundly aware of the ever-present possibility of the magical and the miraculous, as well as of the granite-hard realities. These are undiluted poems, beautifully calculated, informed– even in their darkest moments– with courage and hope.” Patten writes extensively for children as well as adults. He has been described as a highly engaging performer, and gives readings frequently. Over the years he has read alongside such poets as Pablo Neruda, Allen Ginsberg, Stevie Smith, Laurie Lee and Robert Lowell. His books have in recent years been translated into Italian, Spanish, German and Polish. His children’s novel Mr Moon’s Last Case won a special award from the Mystery Writers of America Guild. In 2002 Patten accepted the Cholmondeley Award for services to poetry. Together with Roger McGough and the late Adrian Henri, he was honoured with the Freedom of the City of Liverpool. Selected bibliography Poetry collections for adults * The Mersey Sound * Little Johnny’s Confession * Notes to the Hurrying Man * The Irrelevant Song * Vanishing Trick * Grave Gossip * Love Poems * Storm Damage * Grinning Jack * Armada * Selected Poems Penguin Books * The new Collected Love Poems * The projectionist’s nightmare * Geography lesson Books for children * The Elephant and the Flower * Jumping Mouse * Emma’s Doll * Gargling With Jelly * Mr Moon’s Last Case * Jimmy Tag-Along * Thawing Frozen Frogs * Juggling With Gerbils * The Story Giant * Impossible Parents, illustrated by Arthur Robins (Walker Books, 1994), OCLC 31708253 * The Impossible Parents Go Green, illus. Robins (Walker, 2000) * The Most Impossible Parents, illus. Robins (Walker, 2010) As editor * The Puffin Book of Utterly Brilliant Poetry * The Puffin Book of Modern Children’s Verse References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brian_Patten

Jessie Pope (18 March 1868– 14 December 1941) was an English poet, writer and journalist, who remains best known for her patriotic motivational poems published during World War I. Wilfred Owen directed his 1917 poem Dulce et Decorum Est at Pope, whose literary reputation has faded into relative obscurity as those of war poets such as Owen and Siegfried Sassoon have grown. Early career Born in Leicester, she was educated at North London Collegiate School. She was a regular contributor to Punch, The Daily Mail and The Daily Express, also writing for Vanity Fair, Pall Mall Magazine and the Windsor. Prose editor A lesser-known literary contribution was Pope’s discovery of Robert Tressell’s novel The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, when his daughter mentioned the manuscript to her after his death. Pope recommended it to her publisher, who commissioned her to abridge it before publication. This, a partial bowdlerisation, moulded it to a standard working-class tragedy while greatly downgrading its socialist political content. Verse Other works include Paper Pellets (1907), an anthology of humorous verse. She also wrote verses for children’s books, such as The Cat Scouts (Blackie, 1912) and the following eulogy to her friend, Bertram Fletcher Robinson (published in the Daily Express on Saturday 26 January 1907): Good Bye, kind heart; our benisons preceding, Shall shield your passing to the other side. The praise of your friends shall do your pleading In love and gratitude and tender pride. To you gay humorist and polished writer, We will not speak of tears or startled pain. You made our London merrier and brighter, God bless you, then, until we meet again! War poetry Pope’s war poetry was originally published in The Daily Mail; it encouraged enlistment and handed a white feather to youths who would not join the colours. Nowadays, this poetry is considered to be jingoistic, consisting of simple rhythms and rhyme schemes, with extensive use of rhetorical questions to persuade (and sometimes pressure) young men to join the war. This extract from Who’s for the Game? is typical in style: Who’s for the game, the biggest that’s played, The red crashing game of a fight? Who’ll grip and tackle the job unafraid? And who thinks he’d rather sit tight? Other poems, such as The Call (1915)– “Who’s for the trench– Are you, my laddie?”– expressed similar sentiments. Pope was widely published during the war, apart from newspaper publication producing three volumes: Jessie Pope’s War Poems (1915), More War Poems (1915) and Simple Rhymes for Stirring Times (1916). Criticism Her treatment of the subject is markedly in stark contrast to the anti-war stance of soldier poets such as Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. Many of these men found her work distasteful, Owen in particular. His poem Dulce et Decorum Est was a direct response to her writing, originally dedicated “To Jessie Pope etc.”. A later draft amended this as “To a certain Poetess”, later being removed completely to turn the poem into a general reproach on anyone sympathetic to the war. Pope is prominently remembered first for her pro-war poetry, but also as a representative of homefront female propagandists such as Mrs Humphry Ward, May Wedderburn Cannan, Emma Orczy, and entertainers such as Vesta Tilley. In particular, the poem “War Girls”, similar in structure to her pro-war poetry, states how "No longer caged and penned up/They’re going to keep their end up/Until the khaki soldier boys come marching back". Though largely unknown at the time, the War poets like Nichols, Sassoon and Owen, as well as later writers such as Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, and Richard Aldington, have come to define the experience of the First World War. Reappraisal Pope’s work is today often presented in schools and anthologies as a counterpoint to the work of the War Poets, a comparison by which her pro-war work suffers both technically and politically. Some writers have attempted a partial re-appraisal of her work as an early pioneer of English women in the workforce, while still critical of both the content and artistic merit of her war poetry. Reminded that Pope was primarily a humourist and writer of light verse, her success in publishing and journalism during the pre-war era, when she was described as the “foremost woman humourist” of her day has been overshadowed by her propagandistic war poems. Her verse has been mined for sympathetic portrayals of the poor and powerless, of women urged to be strong and self-reliant. Her portrayal of the Suffragettes in a pair of counterpointed 1909 poems makes a case both for and against their actions. Later life After the war, Pope continued to rewrite, penning a short novel, poems—many of which continued to reflect upon the war and its aftermath—and books for children. She married a widower bank manager in 1929, when she was 61, and moved from London to Fritton, near Great Yarmouth. She died on 14 December 1941 in Devon.

Thomas Parnell (11 September 1679– 24 October 1718) was an Anglo-Irish poet and clergyman who was a friend of both Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift. He was the son of Thomas Parnell of Maryborough, Queen’s County (now Port Laoise, County Laoise), a prosperous landowner who had been a loyal supporter of Cromwell during the English Civil War and moved to Ireland after the restoration of the monarchy. Thomas was educated at Trinity College, Dublin and collated archdeacon of Clogher in 1705. He however spent much of his time in London, where he participated with Pope, Swift and others in the Scriblerus Club, contributing to The Spectator and aiding Pope in his translation of The Iliad. He was also one of the so-called “Graveyard poets”: his ‘A Night-Piece on Death,’ widely considered the first “Graveyard School” poem, was published posthumously in Poems on Several Occasions, collected and edited by Alexander Pope and is thought by some scholars to have been published in December of 1721 (although dated in 1722 on its title page, the year accepted by The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature; see 1721 in poetry, 1722 in poetry). It is said of his poetry 'it was in keeping with his character, easy and pleasing, enunciating the common places with felicity and grace. He died in Chester in 1718 on his way home to Ireland. His wife and children having died, his Laoise estate passed to his brother John, a judge and MP in the Irish House of Commons and the ancestor of Charles Stewart Parnell. Oliver Goldsmith wrote a biography of Parnell which often accompanied later editions of Parnell’s works. Works * Essay on the Different Stiles of Poetry (1713) * Battle of the Frogs and Mice (1717 translation in heroic couplets of a comic epic then attributed to Homer) * An example of his poetry is the opening stanza of his poem The Hermit References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Parnell

Michael Palmer (born May 11, 1943) is an American poet and translator. He attended Harvard University where he earned a BA in French and an MA in Comparative Literature. He has worked extensively with Contemporary dance for over thirty years and has collaborated with many composers and visual artists. Palmer has lived in San Francisco since 1969. Palmer is the 2006 recipient of the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets. This $100,000 (US) prize recognizes outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry. Beginnings Michael Palmer began actively publishing poetry in the 1960s. Two events in the early sixties would prove particularly decisive for his development as a poet. First, he attended the now famous Vancouver Poetry Conference in 1963. This July–August 1963 Poetry Conference in Vancouver, British Columbia spanned three weeks and involved about sixty people who had registered for a program of discussions, workshops, lectures, and readings designed by Warren Tallman and Robert Creeley as a summer course at the University of B.C. There Palmer met writers and artists who would leave an indelible mark on his own developing sense of a poetics, especially Robert Duncan, Robert Creeley, and Clark Coolidge, with whom he formed lifelong friendships. It was a landmark moment as Robert Creeley observed: Vancouver Poetry Conference brought together for the first time, a decisive company of then disregarded poets such as Denise Levertov, Charles Olson, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Duncan, Margaret Avison, Philip Whalen... together with as yet unrecognised younger poets of that time, Michael Palmer, Clark Coolidge and many more.” Palmer’s second initiation into the rites of a public poet began with the editing of the journal Joglars with fellow poet Clark Coolidge. Joglars (Providence, Rhode Island) numbered just three issues in all, published between 1964–66, but extended the correspondence with fellow poets begun in Vancouver. The first issue appeared in Spring 1964 and included poems by Gary Snyder, Michael McClure, Fielding Dawson, Jonathan Williams, Lorine Niedecker, Robert Kelly, and Louis Zukofsky. Palmer published five of his own poems in the second number of Joglars, an issue that included work by Larry Eigner, Stan Brakhage, Russell Edson, and Jackson Mac Low. For those who attended the Vancouver Conference or learned about it later on, it was apparent that the poetics of Charles Olson, proprioceptive or Projectivist in its reach, was exerting a significant and lasting influence on the emerging generation of artists and poets who came to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s. Subsequent to this emerging generation of artists who felt Olson’s impact, poets such as Robert Creeley and Robert Duncan would in turn exert their own huge impact on our national poetries (see also: Black Mountain poets and San Francisco Renaissance). Of this particular company of poets encountered in Vancouver, Palmer says: ...before meeting that group of poets in 1963 at the Vancouver Poetry Conference, I had begun to read them intensely, and they proposed alternatives to the poets I was encountering at that time at Harvard, the confessional poets, whose work was grounded to a greater or lesser degree in New Criticism, at least those were their mentors. The confessional poets struck me as people absolutely lusting for fame, all of them, and they were all trying to write great lines. Early development of poetry and poetics Following the Vancouver Conference, Robert Duncan and Robert Creeley remained primary resources. Both poets had a lasting, active influence on Palmer’s work which has extended until the present. In an essay, “Robert Duncan and Romantic Synthesis” (see 'External links’ below), Palmer recognizes that Duncan’s appropriation and synthesis of previous poetic influences was transformed into a poetics noted for “exploratory audacity... the manipulation of complex, resistant harmonies, and by the kinetic idea of ”composition by field", whereby all elements of the poem are potentially equally active in the composition as 'events’ of the poem". And if this statement marks a certain tendency readers have noted in Palmer’s work all along, or remains a touchstone of sorts, we sense that from the beginning Palmer has consistently confronted not only the problem of subjectivity and public address in poetry, but the specific agency of Poetry and the relationship between poetry and the political: "The implicit... question has always concerned the human and social justification for this strange thing, poetry, when it is not directly driven by the political or by some other, equally other evident purpose [...] Whereas the significant artistic thrust has always been toward artistic independence within the world, not from it.” So for Michael Palmer, this tendency seems there from the beginning. Today these concerns continue through multiple collaborations across the fields of poetry, dance, translation, and the visual arts. Perhaps similar to Olson’s impact on his generation, Palmer’s influence remains singular and palpable, if difficult to measure. Since Olson’s death in 1970, we continue to be, following upon George Oppen’s phrase, carried into the incalculable, As Palmer recently noted in a blurb for Claudia Rankine’s poetic testament Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (2004), ours is “a time when even death and the self have been re-configured as commodities”. Work Palmer is the author of twelve full-length books of poetry, including Thread (2011), Company of Moths (2005) (shortlisted for the 2006 Canadian Griffin Poetry Prize), Codes Appearing: Poems 1979-1988 (2001), The Promises of Glass (2000), The Lion Bridge: Selected Poems 1972-1995 (1998), At Passages (1996), Sun (1988), First Figure (1984), Notes for Echo Lake (1981), Without Music (1977), The Circular Gates (1974), and Blake’s Newton (1972). A prose work, The Danish Notebook, was published in 1999. In the spring of 2007, a chapbook, The Counter-Sky (with translations by Koichiro Yamauchi), was published by Meltemia Press of Japan, to coincide with the Tokyo Poetry and Dance Festival. His work has appeared in literary magazines such as Boundary 2, Berkeley Poetry Review, Sulfur, Conjunctions, Grand Street and O-blek. Besides the 2006 Wallace Stevens Award, Michael Palmer’s honors include two grants from the Literature Program of the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1989-90 he was a Guggenheim Fellow. During the years 1992–1994 he held a Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Fund Writer’s Award. From 1999 to 2004, he served as a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. In the spring of 2001 he received the Shelly Memorial Prize Prize from the Poetry Society of America. Introducing Palmer for a reading at the DIA Arts Center in 1996, Brighde Mullins noted that Palmer’s poetics is both “situated yet active”. Palmer alludes to this himself, perhaps, when he speaks of poetry signaling a “site of passages”. He says, “The space of the page is taken as a site in itself, a syntactical and visual space to be expressively exploited, as was the case with the Black Mountain poets, as well as writers such as Frank O’Hara, perhaps partly in response to gestural abstract painting.” Elsewhere he observes that “in our reading we have to rediscover the radical nature of the poem.” In turn, this becomes a search for “the essential place of lyric poetry” as it delves “beneath it to its relationship with language”. Since he seems to explore the nature of language and its relation to human consciousness and perception, Palmer is often associated with the Language poets (sometimes referred to as the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets, after the magazine that bears that name). Of this particular association, Palmer comments in a recent (2000) interview: It goes back to an organic period when I had a closer association with some of those writers than I do now, when we were a generation in San Francisco with lots of poetic and theoretical energy and desperately trying to escape from the assumptions of poetic production that were largely dominant in our culture. My own hesitancy comes when you try to create, let’s say, a fixed theoretical matrix and begin to work from an ideology of prohibitions about expressivity and the self—there I depart quite dramatically from a few of the Language Poets. Critical reception Michael Palmer’s poetry has received both praise and criticism over the years. Some reviewers call it abstract. Some call it intimate. Some call it allusive. Some call it personal. Some call it political. And some call it inaccessible. While some reviewers or readers may value Palmer’s work as an “extension of modernism”, they criticize and even reject Palmer’s work as discordant: an interruption of our composure (to invoke Robert Duncan’s phrase). Palmer’s own stated poetics will not allow or settle for “vanguard gesturalism”. In a singular confrontion with the modernist project, the poet must suffer 'loss’, embrace disturbance and paradox, and agonize over what cannot be accounted for. It is a poetry that can, at once, gesture toward post-modern, post-avant-garde, semiotic concerns even as it acknowledges that ...the artist after Dante’s poetics, works with all parts of the poem as polysemous, taking each thing of the composition as generative of meaning, a response to and a contribution to the building form.[...]But this putting together and rendering anew operates in our own apprehension of emerging articulations of time. Every particular is an immediate happening of meaning at large; every present activity in the poem redistributes future as well as past events. This is a presence extended in a time we create as we keep words in mind.” We can recognize that the “weary beauty” of Palmer’s work bespeaks the tension and accord he offers toward the Modernists and the vanguardists, even as he is seeking to maintain or at least continue to search for an ethics of the I/Thou. It is an awkward truce we make with modernism when there is no cessation of hostilities. But sometimes in reading Palmer’s work we recognize (almost against ourselves) a poetry that is described as surreal in context and contour, livid in aural accomplishment, but all the while confronts the reader with a poetics both active and situated. And if Palmer is sometimes praised for this, more often than not he is criticized, rebuked, vilified and dismissed (just as Paul Celan was) for hermeticism, deliberate obscurity, and bogus erudition. Palmer admits to a stated “essential errancy of discovery in the poem” that would not necessarily be a “unified narrative explanation of the self”, but would allow for itself “cloaked meaning and necessary semantic indirection” Confrontation with Modernism He remains candid about the giants of modernism: i.e., Yeats, Eliot and Pound. Whether it is the fascism of Ezra Pound or the less overt but no less insidious anti-semitism found in the work of T. S. Eliot, Palmer’s position is a fierce rejection of their politics, but qualified with the acknowledgment that, as Marjorie Perloff has observed of Pound, “he remains the great inventor of the period, the poet who really MADE THINGS NEW”. Thus, Palmer decries that what remains for us is something quite harrowing “inscribed at the heart of modernism”. Perhaps we can invoke one of Palmer’s real 'heroes’, Antonio Gramsci, and say here, now, what precisely has been inscribed over against what today (in the vicious circles of media and cultural production) is merely forecast as cultural hegemony. So if Palmer, on the one hand, variously describes or defines an Ideology as that which “invades the field of meaning”, we recognize not only in Pound or Eliot, but now as if against ourselves, that ideology implicitly deploys values and premises that must remain unspoken in order for them to function as ideology or to remain hidden in plain sight, as such. At some point we can invoke the 'post-ideological’ stance of Slavoj Žižek who, after Althusser, jettisons the Marxist equation: ideology=false consciousness and say that, perhaps Ideology, to all intents and purposes, IS consciousness. As a way out of this seeming double-bind, or to his admissions that poetry is, as Pound observed, “news that stays news”, that it remains an active and viable (or “actively situated”) principle within the social dynamic, critics and readers alike point to Palmer’s own avowals of an emerging countertradition to the prevailing literary establishment: an 'alternative tradition’ that just slipped under the radar as far as the Academy and its various 'schools’ of poetry are concerned. Though not always so visible, this counter-tradition continues to exert an underground influence. Poetry, as critique or praise, can perhaps in its reach exceed the grasp of modernism and procure for us as visible again, that which is all or nothing except for the 'ghostlier demarcations’ of the social wager within sight of the shipwreck of the singular (as George Oppen characterized it) which denotes or delimits the very idea of the social, if not the very idea that there is a definition of the social other than this: the community of those who have no community. Indeed, the unavowable community (to borrow a title and phrasing from Maurice Blanchot). Faced with shipwreck, “in the dark” amidst the ravished heresies of the unspoken as even against silence itself, we can think with the poem. With fierce determination or graceful adherence we can perhaps even “see” with the poem, account for its usefulness. Even as we use the language, attend to its fissures and abhorrences, language in turn uses us, or has its own uses for us, as Palmer attests: Palmer has repeatedly stated, in interviews and in various talks given across the years, that the situation for the poet is paradoxical: a seeing which is blind, a “nothing you can see”, an “active waiting”, “purposive, sometimes a music”, or a “nowhere” that is "now / here". For Palmer, it is a situation which is never over, and yet it mysteriously starts up again each day, as if describing a circle. Poetry can “interrogate the radical and violent instability of our moment, asking where is the location of culture, where the site of self, selves, among others” (as Palmer has characterized the poetry of Myung Mi Kim). Collaborations Palmer has published translations from French, Russian and Brazilian Portuguese, and has engaged in multiple collaborations with painters. These include the German painter Gerhard Richter, French painter Micaëla Henich, and Italian painter Sandro Chia. He edited and helped translate Nothing The Sun Could Not Explain: Twenty Contemporary Brazilian Poets (Sun & Moon Press, 1997). With Michael Molnar and John High, Palmer helped edit and translate a volume of poetry by the Russian poet Alexei Parshchikov, Blue Vitriol (Avec Books, 1994). He also translated “Theory of Tables” (1994), a book written by Emmanuel Hocquard, a project that grew out of Hocquard’s translations of Palmer’s “Baudelaire Series” into French. Palmer has written many radio plays and works of criticism. But his lasting significance occurs as the singular concerns of the artist extend into the aleatory, the multiple, and the collaborative. Dance For more than thirty years he has collaborated on over a dozen dance works with Margaret Jenkins and her Dance Company. Early dance scenarios in which Palmer participated include Interferences, 1975; Equal Time, 1976; No One but Whitington, 1978; Red, Yellow, Blue, 1980, Straight Words, 1980; Versions by Turns, 1980; Cortland Set, 1982; and First Figure, 1984. A particularly noteworthy example of a recent Jenkins/Palmer collaboration would be The Gates (Far Away Near), an evening-length dance work in which Palmer worked with not only Ms. Jenkins, but also Paul Dresher and Rinde Eckert. This was performed in September 1993 in the San Francisco Bay Area and in July 1994 at New York’s Lincoln Center. Another recent collaboration with Jenkins resulted in “Danger Orange”, a 45-minute outdoor site-specific performance, presented in October 2004 before the Presidential elections. The color orange metaphorically references the national alert systems that are in place that evoke the sense of danger.[see also:Homeland Security Advisory System] Painters and visual artists Similar to his friendship with Robert Duncan and the painter Jess Collins, Palmer’s work with painter Irving Petlin remains generative. Irving’s singular influence from the beginning demonstrated for Palmer a “working” of the poet as “maker” (in the radical sense, even ancient sense of that word). Along with Duncan, Zukofsky, and others, Petlin’s work modeled, demonstrated, circumscribed and, perhaps most importantly for Palmer, verified that “the way” (this way for the artist who is a maker, a creator) would also be, as Gilles Deleuze termed it, “a life”. This in turn delineates Palmer’s own sense of both a poetics and an ongoing counter-poetic tradition, offering him fixture and a place of repair. Recently he worked with painter and visual artist Augusta Talbot, and curated her exhibition at the CUE Art Foundation (March 17 –April 23, 2005). When asked in an interview how collaboration has pushed the boundaries of his work, Palmer responded: There were a variety of influences. One was that, when I was using language—but even when I wasn’t, when I was simply envisioning a structure, for example—I was working with the idea of actual space. Over time, my own language took on a certain physicality or gestural character that it hadn’t had as strongly in the earliest work. Margy (Margaret Jenkins) and I would often work with language as gesture and gesture as language—we would cross these two media, have them join at some nexus. And inevitably then, as I brought certain characteristics of my work to dance, and to dance structure and gesture, it started crossing over into my work. It added space to the poems. It may be that for Palmer, friendship (acknowledging both the multiple and collaborative), becomes in part what Jack Spicer terms a “composition of the real”. Across the fields of painting and dance, Palmer’s work figures as an “unrelenting tentacle of the proprioceptive”. Furthermore, it may signal a Coming Community underscored in the work of Giorgio Agamben, Jean-Luc Nancy and Maurice Blanchot among others. It is a poetry that would, along with theirs, articulate a place for, even spaces where, both the “poetic imaginary” is constituted and a possible social space is envisioned. As Jean-Luc Nancy has written in The Inoperative Community (1991): “These places, spread out everywhere, yield up and orient new spaces... other tracks, other ways, other places for all who are there.” Bibliography Poetry * Plan of the City of O, Barn Dreams Press (Boston, Massachusetts), 1971. * Blake’s Newton, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, California), 1972. * C’s Songs, Sand Dollar Books (Berkeley, California), 1973. * Six Poems, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, California), 1973. * The Circular Gates, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, California), 1974. * (Translator, with Geoffrey Young) Vicente Huidobro, Relativity of Spring: 13 Poems, Sand Dollar Books (Berkeley, California), 1976. * Without Music, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, California), 1977. * Alogon, Tuumba Press (Berkeley, California), 1980. * Notes for Echo Lake, North Point Press (Berkeley, California), 1981. * (Translator) Alain Tanner and John Berger, Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000, North Atlantic Books (Berkeley, California), 1983. * First Figure, North Point Press (Berkeley, California), 1984. * Sun, North Point Press (Berkeley, California), 1988. * At Passages, New Directions (New York, New York), 1995. * The Lion Bridge: Selected Poems, 1972-1995, New Directions (New York, New York), 1998. * The Promises of Glass, New Directions (New York, New York), 2000. * Codes Appearing: Poems, 1979-1988, New Directions (New York, New York), 2001. Notes for Echo Lake, First Figure, and Sun together in one volume. ISBN 978-0-8112-1470-4 * (With Régis Bonvicino) Cadenciando-um-ning, um samba, para o outro: poemas, traduções, diálogos, Atelieì Editorial (Cotia, Brazil), 2001. * Company of Moths, New Directions (New York, New York), 2005. ISBN 978-0-8112-1623-4 * Aygi Cycle, Druksel (Ghent, Belgium), 2009 (chapbook with 10 new poems, inspired by the Russian poet Gennadiy Aygi. * (With Jan Lauwereyns) Truths of Stone, Druksel (Ghent, Belgium), 2010. * Thread, New Directions (New York, New York), 2011. ISBN 978-0-8112-1921-1 * The Laughter of the Sphinx, New Directions (New York, New York), 2016. ISBN 978-0-8112-2554-0 Other * Idem 1-4 (radio plays), 1979. * (Editor) Code of Signals: Recent Writings in Poetics, North Atlantic Books (Berkeley, California), 1983. * The Danish Notebook, Avec Books (Penngrove, California), 1999—prose/memoir * Active Boundaries: Selected Essays and Talks, New Directions (New York, New York), 2008. ISBN 0-8112-1754-X External links Palmer sites and exhibits * Exhibit at The Academy of American Poets includes links to on-line poems by Palmer not listed below * Modern American Poetry site * Author Page at Internationales Literatufestival Berlin site (in English) Palmer was a guest of the ILB (Internationales Literatufestival Berlin/ Germany) in 2001 and 2005. * An internet bibliography for Michael Palmer from LiteraryHistory.com Poems * “Dream of a Language That Speaks” a poem from Company of Moths (2005) @ Jacket Magazine site * “Scale” first published in Richter 858 (ed. David Breskin, The Shifting Foundation, SF MOMA: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art); included in Company of Moths * "Autobiography 3" & Autobiography 5" two poems from Conjunctions magazine’s on-line archive; included in The Promises of Glass (2000) * To the Title (Are there titles?) included in Jacket Magazine 33 * four poems from Thread from Boston Review’s March/April 2010 issue * Late Night Poetry @ Tony Bilson’s Number One: Palmer reads “The Dream of Narcissus” on YouTube Video of Palmer at the 2010 Sydney (Australia) Writers Festival. * Michael Palmer reads Mahmoud Darwish’s “The Strangers’ Picnic” on YouTube Video of Palmer reading a poem from Mahmoud Darwish’s collection Unfortunately, It Was Paradise: Selected Poems * Michael Palmer, Paul Hoover with the poetry of Maria Baranda - September 27, 2015– Palmer reads from his book Thread and from his forthcoming collection The Laughter of the Sphinx. He also reads a single poem from his collection The Company of Moths. Selected essays and talks * Period (senses of duration) this is a version of a talk Palmer gave in San Francisco in February 1982. Scroll down to “Table of Contents” to find the Palmer selection. Here it appears in an e-book representation of Code of Signals (which Palmer edited in 1983, with the subtitle “Recent Writings in Poetics”). * On Robert Duncan reprint of Palmer’s essay “Robert Duncan and Romantic Synthesis” * Michael Palmer audio-files at PENNsound * “On the Sustaining of Culture in Dark Times” text of Palmer’s keynote address given at the 3rd Annual Sustainable Living Conference at Evergreen State College in February 2004 * “Ground Work: On Robert Duncan” Michael Palmer’s “Introduction” to a combined edition of Ground Work: Before the War, and Ground Work II: In the Dark, published by New Directions in April 2006. * Lunch Poems reading by Michael Palmer: Webcast Held on October 5, 2006, in the Morrison Library, University of California at Berkeley: webcast online * “In Company: On Artistic Collaboration and Solitude” This is the title of the lecture/talk that Palmer gave, along with a poetry reading, at the University of Chicago in October 2006. (In audio & video format) * Bad to the bone: What I learned outside Lecture & Talk given in June 2002, when Palmer taught for a brief stint at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa in Boulder, Colorado * Poetic Obligations (Talking about Nothing at Temple) This is a talk Palmer gave at Temple University in February 1999, and was originally published in Fulcrum: An annual of poetry and aesthetics (Issue 2, 2003). * Poetry and Contingency: Within a Timeless Moment of Barbaric Thought essay/talk originally published in the Chicago Review (June, 2003) Interviews with Palmer * The River City Interview conducted by Paul Naylor, Lindsay Hill, and J. P. Craig; appeared in 1994. * An Interview with Michael Palmer by Robert Hicks in 2006 * Interview at Berkeley Daily Planet: April 7, 2006 discusses a reading Palmer & Douglas Blazek gave together at Moe’s, a bookstore in Berkeley, California; includes interviews * Interview with Michael Palmer an interview conducted at Washington University in St. Louis in 2008 by the student editors of “Arch Literary Journal” in conjunction with a talk and reading Palmer gave at the school. Includes an introductory essay by one of the editors, Lawrence Revard, “'What Reading?': Play in Michael Palmer’s Poetics” * “An interview with Michael Palmer”. Litshow.com. 2013-02-13. Retrieved 2013-04-23. Others on Palmer * Margaret Jenkins Dance Company info on both Palmer & his collaborators in their on-going work with Dance * Lauri Ramey:"Michael Palmer: The Lion Bridge" Ramey wrote a doctoral dissertation on Palmer, and here reviews his “Selected Poems” * A Collision of “Possible Worlds” A 2002 review of The Promises of Glass by Michael Dowdy @Free Verse website * A review of Company of Moths a book review of Palmer’s 2005 collection * Griffin Poetry Prize biography, including audio and video clips Palmer was shortlisted for this prize in 2006 * Margaret Jenkins Dance Company’s “A Slipping Glimpse” 2006 dance piece in collaboration with Tanushree Shankar Dance School & the text by Palmer * Cultural camaraderie article from Hindustantimes.com on the dance performance A Slipping Glimpse. Article discusses Palmer’s collaboration (includes quotes) * Palmer is Spring 2007 Writer in Residence press release from California College of the Arts * Michael Palmer (Six Introductions) a brief essay by Clayton Eshleman who edited Sulfur magazine, for which Palmer served as a contributing editor. * Hands Across Many Seas: From San Francisco and India, a dance collaboration article by Deborah Jowitt on “A Slipping Glimpse”, performed by the Margaret Jenkins Dance Company at the “Danspace Project” at Saint Mark’s Church, October 4 through 6, 2007 * Lyric Persuasions at Poets House Rae Armantrout and Zoketsu Norman Fischer discuss Michael Palmer’s work as recorded by Vasiliki Katsarou at the Poet’s House in the Spring of 2010 References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Palmer_(poet)

Henry James Pye (/paɪ/; 10 February 1744– 11 August 1813) was an English poet. Pye was Poet Laureate from 1790 until his death. He was the first poet laureate to receive a fixed salary of £27 instead of the historic tierce of Canary wine (though it was still a fairly nominal payment; then as now the Poet Laureate had to look to extra sales generated by the prestige of the office to make significant money from the Laureateship). Life Pye was born in London, the son of Henry Pye of Faringdon House in Berkshire, and his wife, Mary James. He was the nephew of Admiral Thomas Pye. He was educated at Magdalen College, Oxford. His father died in 1766, leaving him a legacy of debt amounting to £50,000, and the burning of the family home further increased his difficulties. In 1784 he was elected Member of Parliament for Berkshire. He was obliged to sell the paternal estate, and, retiring from Parliament in 1790, became a police magistrate for Westminster. Although he had no command of language and was destitute of poetic feeling, his ambition was to obtain recognition as a poet, and he published many volumes of verse. Of all he wrote his prose Summary of the Duties of a Justice of the Peace out of Sessions (1808) is most worthy of record. He was made poet laureate in 1790, perhaps as a reward for his faithful support of William Pitt the Younger in the House of Commons. The appointment was looked on as ridiculous, and his birthday odes were a continual source of contempt. The 20th century British historian Lord Blake called Pye “the worst Poet Laureate in English history with the possible exception of Alfred Austin.” Indeed, Pye’s successor, Robert Southey, wrote in 1814: “I have been rhyming as doggedly and dully as if my name had been Henry James Pye.” After his death, Pye remained one of the unfortunate few who have been classified as a “poetaster.” As a prose writer, Pye was far from contemptible. He had a fancy for commentaries and summaries. His “Commentary on Shakespeare’s commentators”, and that appended to his translation of the Poetics, contain some noteworthy matter. A man, who, born in 1745, could write “Sir Charles Grandison is a much more unnatural character than Caliban,” may have been a poetaster but was certainly not a fool. He died in Pinner, Middlesex on 11 August 1813. Pye married twice. He had two daughters by his first wife. He married secondly in 1801 Martha Corbett, by whom he had a son Henry John Pye, who in 1833 inherited the Clifton Hall, Staffordshire estate of a distant cousin and who was High Sheriff of Staffordshire in 1840. Works Prose * Summary of the Duties of a Justice of the Peace out of Sessions (1808) * The Democrat (1795) * The Aristocrat (1799) Poetry * Poems on Various Subjects (1787), first substantial collection of Pye’s verse * Adelaide: a Tragedy in Five Acts (1800) * Alfred (1801) Translations * Aristotle’s Poetics (1792) References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_James_Pye

Lots of college, lots of work, a few spells in a mental ward. I have Apserger Syndrome and it was never diagnosed until a doctor asked me to research and find for myself what was wrong with me. Hard to believe my own diagnosis, years later it sunk in. Now devoid of drugs, still love alcohol, I read philosophy, try to give as little advice as I can (the burden is too great), Love music, play a little guitar and a full size one :) I like to watch movies and TV series to relax as I have given up fiction unless its a classic. I love my motorbike, I love women. I keep to myself having read that as good advice for reasons that shall remain blurred (I have a few reasons and a few good friends). I have been writing poetry for years now and mostly in deep depression so many of the poems I may add are from years gone by and maybe rewritten a little. Recently I have began to write not out of depression but out of love of myself and lack of it for society, and that is not meant against any individual, just the way life works....and works.....and works. As time goes by lots more modern poetry has been added by me. I wish for something greater than what is. Greater than I am. As Great as it can be. I believe in God. I believe in myself.