Info

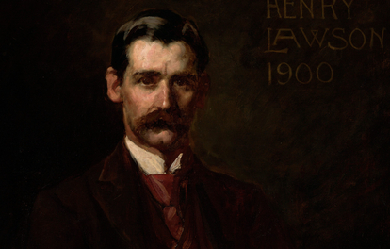

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period and is often called Australia's “greatest short story writer”. He was the son of the poet, publisher and feminist Louisa Lawson.

Philip Arthur Larkin (9 August 1922 – 2 December 1985) was an English poet and novelist. His first book of poetry, The North Ship, was published in 1945, followed by two novels, Jill (1946) and A Girl in Winter (1947), but he came to prominence in 1955 with the publication of his second collection of poems, The Less Deceived, followed by The Whitsun Weddings (1964) and High Windows (1974). He was the recipient of many honours, including the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry. He was offered, but declined, the position of poet laureate in 1984, following the death of John Betjeman.

Rare & Strange...Lover of Wine, Sports, Skulls, The Sun, All Things Fast, Giving & Taking Chances, People Watching, Music, Poetry, Animals, Dialogue, Sensuality, Sexuality, Passion & Passionate People, Confidence, Art, Movies, Conversations, Romance, Philosophy & Johnny Depp.....Watching movies that make you think - like A waking life or with great dialogue. It's all about the lighting... What makes us different, you & I? I'm on my life mission of seeking the strange, yet the similar, the one who will make me think, make me not think, who will drive me wild with words, passion and love. I wear my heart on my sleeve and won't stop to let the world take away my spirit. I refuse to settle even if it means I never stop ...but I know he's out there my eclectic twin soul who will love adventure, random rants, giving and caring for others, fitting in between the cracks with me and standing out in the crowd too. Intelligent and Cultured , both city and country lover, who will pack up run through the mountains taking random photos of cemeteries and visions in the clouds, who will jump on a horse and ride a wild ride with me...a best friend, a soul mate, the other half who inspires me and I inspire he and long talks with large glasses of wine and endless nights in electric passion ...tantric, twisted, non-judging just accepting each other completely, swallowing each other ...

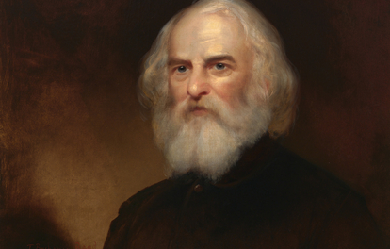

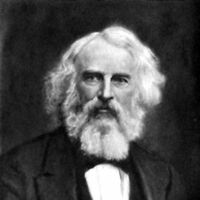

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator whose works include "Paul Revere's Ride", The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline. He was also the first American to translate Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy and was one of the five Fireside Poets. Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, then part of Massachusetts, and studied at Bowdoin College. After spending time in Europe he became a professor at Bowdoin and, later, at Harvard College. His first major poetry collections were Voices of the Night (1839) and Ballads and Other Poems (1841). Longfellow retired from teaching in 1854 to focus on his writing, living the remainder of his life in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a former headquarters of George Washington. His first wife, Mary Potter, died in 1835 after a miscarriage. His second wife, Frances Appleton, died in 1861 after sustaining burns from her dress catching fire. After her death, Longfellow had difficulty writing poetry for a time and focused on his translation. He died in 1882.

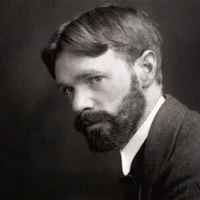

David Herbert Richards Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic and painter who published as D. H. Lawrence. His collected works represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. In them, Lawrence confronts issues relating to emotional health and vitality, spontaneity, and instinct. Lawrence’s opinions earned him many enemies and he endured official persecution, censorship, and misrepresentation of his creative work throughout the second half of his life, much of which he spent in a voluntary exile which he called his “savage pilgrimage”. At the time of his death, his public reputation was that of a pornographer who had wasted his considerable talents. E. M. Forster, in an obituary notice, challenged this widely held view, describing him as, “The greatest imaginative novelist of our generation”. Later, the influential Cambridge critic F. R. Leavis championed both his artistic integrity and his moral seriousness, placing much of Lawrence's fiction within the canonical “great tradition” of the English novel. Lawrence is now valued by many as a visionary thinker and significant representative of modernism in English literature.

I'm a social science student with an interest in philosophy, sociology and anthropology particularly. I would describe myself as a highly sensitive person but forever the optimist. Music is more than a hobby of mine, it is a way of life. I wear my heart on my sleeve and because of this I am a songwriter, musician and occasional poet. Instagram username- Marnoldkins

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school from Brookline, Massachusetts, who posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. Amy was born into Brookline’s Lowell family, sister to astronomer Percival Lowell and Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. She never attended college because her family did not consider it proper for a woman to do so. She compensated for this lack with avid reading and near-obsessive book collecting. She lived as a socialite and travelled widely, turning to poetry in 1902 (age 28) after being inspired by a performance of Eleonora Duse in Europe.

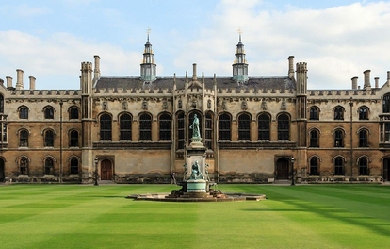

Richard Lovelace (1618–1657) was an English poet in the seventeenth century. He was a cavalier poet who fought on behalf of the king during the Civil war. His best known works are To Althea, from Prison, and To Lucasta, Going to the Warres. Early life and family Richard Lovelace was born in 1618. His exact birthplace is unknown, but it is documented that it was either Woolwich, Kent, or Holland. He was the oldest son of Sir William Lovelace and Anne Barne Lovelace and had four brothers and three sisters. His father was from an old distinguished military and legal family and the Lovelace family owned a considerable amount of property in Kent. His father, Sir William Lovelace, knt., was a member of the Virginia Company and an incorporator in the second Virginia Company in 1609. He was a soldier and he died during the war with Spain and Holland in the siege of Grol, a few days before the town fell. Richard was only 9 years old when his father died. Richard's father was the son of Sir William Lovelace and Elizabeth Aucher who was the daughter of Mabel Wroths and Edward Aucher, Esq. who inherited, under his father's Will, the manors of Bishopsbourne and Hautsborne. Elizabeth's nephew was Sir Anthony Aucher (1614 – 31 May 1692) an English politician and Cavalier during the English Civil War. He was the son of her brother Sir Anthony Aucher and his wife Hester Collett. Richard Lovelace's mother, Anne Barne (1587–1633), was the daughter of Sir William Barne and the granddaughter of Sir George Barne III (1532- d. 1593), the Lord Mayor of London and a prominent merchant and public official from London during the reign of Elizabeth I; and Anne Gerrard, daughter of Sir William Garrard, who was Lord Mayor of London in 1555. Richard Lovelace's mother was also the daughter of Anne Sandys and the granddaughter of Cicely Wilford and the Most Reverend Dr. Edwin Sandys, an Anglican church leader who successively held the posts of the Bishop of Worcester (1559–1570), Bishop of London (1570–1576), and the Archbishop of York (1576–1588). He was one of the translators of the Bishops' Bible. Anne Barne Lovelace married as her second husband, on 20 January 1630, at Greenwich, England, the Very Rev. Dr. Jonathan Browne They were the parents of one child, Anne Browne, who married Herbert Crofte, S.T.P. and D.D and were the parents of Sir Herbert Croft, 1st Baronet. His brother, Francis Lovelace (1621–1675), was the second governor of the New York colony appointed by the Duke of York, later King James II of England. He was also the great nephew of both George Sandys (2 March 1577 – March 1644), an English traveller, colonist and poet; and of Sir Edwin Sandys (9 December 1561 – October 1629), an English statesman and one of the founders of the London Company. In 1629, when Lovelace was eleven, he went to Sutton’s Foundation at Charterhouse School, then located in London. However, there is not a clear record that Lovelace actually attended because it is believed that he studied as a “boarder” because he did not need financial assistance like the “scholars”. He spent five years at Charterhouse, three of which were spent with Richard Crashaw, who also became a poet. On 5 May 1631, Lovelace was sworn in as a “Gentleman Wayter Extraordinary” to the King. This was an “honorary position for which one paid a fee”. He then went on to Gloucester Hall, Oxford, in 1634. Collegiate career Richard Lovelace attended Oxford University and he was praised by one of his contemporaries, Anthony Wood. for being “the most amiable and beautiful person that ever eye beheld; a person also of innate modesty, virtue and courtly deportment, which made him then, but especially after, when he retired to the great city, much admired and adored by the female sex" At the age of eighteen, during a three-week celebration at Oxford, he was granted the degree of Master of Arts. While at school, he tried to portray himself more as a social connoisseur rather than a scholar, continuing his image of being a Cavalier. Being a Cavalier poet, Lovelace wrote to praise a friend or fellow poet, to give advice in grief or love, to define a relationship, to articulate the precise amount of attention a man owes a woman, to celebrate beauty, and to persuade to love. Lovelace wrote a comedy, 'The Scholars,' and a tragedy titled 'The Soldiers,' while at Oxford. He then left for Cambridge University for a few months where he met Lord Goring, who led him into political trouble. Politics and prison Lovelace’s poetry was often influenced by his experiences with politics and association with important figures of his time. At the age of thirteen, Lovelace became a "Gentlemen Wayter Extraordinary" to the King and at nineteen he contributed a verse to a volume of elegies commemorating Princess Katharine. In 1639 Lovelace joined the regiment of Lord Goring, serving first as a senior ensign and later as a captain in the Bishops’ Wars. This experience inspired the 'Sonnet. To Generall Goring.' Upon his return to his home in Kent in 1640, Lovelace served as a country gentleman and a justice of the peace where he encountered firsthand the civil turmoil regarding religion and politics. In 1641 Lovelace led a group of men to seize and destroy a petition for the abolition of Episcopal rule, which had been signed by fifteen thousand people. The following year he presented the House of Commons with Dering’s pro-Royalist petition which was supposed to have been burned. These actions resulted in Lovelace’s first imprisonment. Shortly thereafter, he was released on bail with the stipulation that he avoid communication with the House of Commons without permission. This prevented Lovelace, who had done everything to prove himself during the Bishops’ Wars, from participating in the first phase of the English Civil War. However, this first experience of imprisonment did result in some good, as it brought him to write one of his finest and most beloved lyrics, 'To Althea, from Prison,' in which he illustrates his noble and paradoxical nature. Lovelace did everything he could to remain in the king’s favor despite his inability to participate in the war. Richard Lovelace did his part again during the political chaos of 1648, though it is unclear specifically what his actions were. He did, however, manage to warrant himself another prison sentence; this time for nearly a year. When he was released in April 1649, the king had been executed and Lovelace’s cause seemed lost. As in his previous incarceration, this experience led to creative production—this time in the form of spiritual freedom, as reflected in the release of his first volume of poetry, Lucasta. Literature Richard Lovelace first started writing while he was a student at Oxford and wrote almost 200 poems from that time until his death. His first work was a drama titled The Scholars. The play was never published; however, it was performed at college and then in London. In 1640, he wrote a tragedy titled 'The Soldier' which was based on his own military experience. When serving in the Bishops' Wars, he wrote the sonnet 'To Generall Goring,' which is a poem of Bacchanalian celebration rather than a glorification of military action. One of his extremely famous poems is 'To Lucasta, Going to the Warres,' written in 1640 and exposed in his first political action. During his first imprisonment in 1642, he wrote his most famous poem 'To Althea, From Prison.' Later on that year during his travels to Holland with General Goring, he wrote 'The Rose,' following with 'The Scrutiny' and on 14 May 1649, 'Lucasta' was published. He also wrote poems analyzing the details of many simple insects. 'The Ant,' 'The Grasse-hopper,' 'The Snayl,' 'The Falcon,' 'The Toad and Spyder.' Of these poems, 'The Grasse-hopper' is his most well-known. In 1660, after Lovelace died, "Lucasta: Postume Poems" was published; it contains 'A Mock-Song,' which has a much darker tone than his previous works. William Winstanley, who praised much of Richard Lovelace's works, thought highly of him and compared him to an idol; "I can compare no Man so like this Colonel Lovelace as Sir Philip Sidney,” of which it is in an Epitaph made of him; Nor is it fit that more I should aquaint Lest Men adore in one A Scholar, Souldier, Lover, and a Saint His most quoted excerpts are from the beginning of the last stanza of To Althea, From Prison: Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron bars a cage; Minds innocent and quiet take That for an hermitage and the end of To Lucasta. Going to the Warres: I could not love thee, dear, so much, Lov'd I not Honour more. Chronology 1618- Richard Lovelace born, either in Woolwich, Kent, or in Holland. 1629- King Charles I nominated “Thomas [probably Richard] Lovelace,” upon petition of Lovelace’s mother, Anne Barne Lovelace, to Sutton’s foundation at Charterhouse. 1631- On 5 May, Lovelace is made “Gentleman Wayter Extraordinary” to the King. 1634- On 27 June, he matriculates as Gentleman Commoner at Gloucester Hall, Oxford. 1635- Writes a comedy, The Scholars. 1636- On 31 August, the degree of M.A. is presented to him. 1637- On 4 October, he enters Cambridge University. 1638-1639- His first printed poems appear: ‘An Elegy” on Princess Katherine; prefaces to several books. 1639- He is senior ensign in General Goring’s regiment - in the First Scottish Expedition. “Sonnet to Goring.” 1640- Commissioned captain in the Second Scottish Expedition; writes a tragedy, The Soldier. He then returns home at 21, into the possession of his family’s property. 1641- Lovelace tears up a pro-Parliament, anti-Episcopacy petition at a meeting in Maidstone, Kent. 1642- 30 April, he presents the anti-Parliamentary Petition of Kent and is imprisoned at Gatehouse. After appealing, he is released on bail, 21 June. The Civil war begins on 22 August, he writes “To Althea, from Prison,” “To Lucasta.” In September, he goes to Holland with General Goring. He writes “The Rose.” 1642-1646-Probably serves in Holland and France with General Goring. He writes “The Scrutiny.” 1643- Sells some of his property to Richard Hulse. 1646- In October, he is wounded at Dunkirk, while fighting under the Great Conde against the Spaniards. 1647- He is admitted to the Freedom at the Painters’ Company. 1648-On 4 February, Lucasta is licensed at the Stationer’s Register. On 9 June, Lovelace is again imprisoned at Peterhouse. 1649- On 9 April, he is released from jail. He then sells the remaining family property and portraits to Richard Hulse. On 14 May, Lucasta is published. 1650-1657- Lovelace’s whereabouts unknown, though various poems are written. 1657- Lovelace dies. 1659-1660- Lucasta, Postume Poems is published. References Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Lovelace

Archibald Lampman FRSC (17 November 1861– 10 February 1899) was a Canadian poet. “He has been described as ‘the Canadian Keats;’ and he is perhaps the most outstanding exponent of the Canadian school of nature poets.” The Canadian Encyclopedia says that he is "generally considered the finest of Canada’s late 19th-century poets in English.” Lampman is classed as one of Canada’s Confederation Poets, a group which also includes Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, and Duncan Campbell Scott. Life Archibald Lampman was born at Morpeth, Ontario, a village near Chatham, the son of Archibald Lampman, an Anglican clergyman. “The Morpeth that Lampman knew was a small town set in the rolling farm country of what is now western Ontario, not far from the shores of Lake Erie. The little red church just east of the town, on the Talbot Road, was his father’s charge.” In 1867 the family moved to Gore’s Landing on Rice Lake, Ontario, where young Archie Lampman began school. In 1868 he contracted rheumatic fever, which left him lame for some years and with a permanently weakened heart. Lampman attended Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ontario, and then Trinity College in Toronto, Ontario (now part of the University of Toronto), graduating in 1882. While at university, he published early poems in Acta Victoriana, the literary journal of Victoria College. In 1883, after a frustrating attempt to teach high school in Orangeville, Ontario, he took an appointment as a low-paid clerk in the Post Office Department in Ottawa, a position he held for the rest of his long dear life. Lampman “was slight of form and of middle height. He was quiet and undemonstrative in manner, but had a fascinating personality. Sincerity and high ideals characterized his life and work.” On Sep. 3, 1887, Lampman married 20-year-old Maude Emma Playter. "They had a daughter, Natalie Charlotte, born in 1892. Arnold Gesner, born May 1894, was the first boy, but he died in August. A third child, Archibald Otto, was born in 1898." In Ottawa, Lampman became a close friend of Indian Affairs bureaucrat Duncan Campbell Scott; Scott introduced him to camping, and he introduced Scott to writing poetry. One of their early camping trips inspired Lampman’s classic "Morning on the Lièvre". Lampman also met and befriended poet William Wilfred Campbell. Lampman, Campbell, and Scott together wrote a literary column, “At the Mermaid Inn,” for the Toronto Globe from February 1892 until July 1893. (The name was a reference to the Elizabethan-era Mermaid Tavern.) As Lampman wrote to a friend: Campbell is deplorably poor.... Partly in order to help his pockets a little Mr. Scott and I decided to see if we could get the Toronto “Globe” to give us space for a couple of columns of paragraphs & short articles, at whatever pay we could get for them. They agreed to it; and Campbell, Scott and I have been carrying on the thing for several weeks now. “In the last years of his short life there is evidence of a spiritual malaise which was compounded by the death of an infant son [Arnold, commemorated in the poem “White Pansies”] and his own deteriorating health." Lampman died in Ottawa at the age of 37 due to a weak heart, an after-effect of his childhood rheumatic fever. He is buried, fittingly, at Beechwood Cemetery, in Ottawa, a site he wrote about in the poem “In Beechwood Cemetery” (which is inscribed at the cemetery’s entranceway). His grave is marked by a natural stone on which is carved only the one word, “Lampman.”. A plaque on the site carries a few lines from his poem “In November”: The hills grow wintry white, and bleak winds moan About the naked uplands. I alone Am neither sad, nor shelterless, nor gray Wrapped round with thought, content to watch and dream. Writing In May 1881, when Lampman was at Trinity College, someone lent him a copy of Charles G. D. Roberts’s recently published first book, Orion and Other Poems. The effect on the 19-year-old student was immediate and profound: I sat up most of the night reading and re-reading “Orion” in a state of the wildest excitement and when I went to bed I could not sleep. It seemed to me a wonderful thing that such work could be done by a Canadian, by a young man, one of ourselves. It was like a voice from some new paradise of art, calling to us to be up and doing. A little after sunrise I got up and went out into the college grounds... everything was transfigured for me beyond description, bathed in an old world radiance of beauty; the magic of the lines was sounding in my ears, those divine verses, as they seemed to me, with their Tennyson-like richness and strange earth-loving Greekish flavour. I have never forgotten that morning, and its influence has always remained with me. Lampman sent Roberts a fan letter, which "initiated a correspondence between the two young men, but they probably did not meet until after Roberts moved to Toronto in late September 1883 to become the editor of Goldwin Smith’s The Week.” Inspired, Lampman also began writing poetry, and soon after began publishing it: first “in the pages of his college magazine, Rouge et Noir;” then “graduating to the more presitigious pages of The Week”– (his sonnet “A Monition,” later retitled “The Coming of Winter,” appeared in its first issue )– and finally, by the late 1880s “winning an audience in the major magazines of the day, such as Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, and Scribner’s.” Lampman published mainly nature poetry in the current late-Romantic style. “The prime literary antecedents of Lampman lie in the work of the English poets Keats, Wordsworth, and Arnold,” says the Gale Encyclopedia of Biography, “but he also brought new and distinctively Canadian elements to the tradition. Lampman, like others of his school, relied on the Canadian landscape to provide him with much of the imagery, stimulus, and philosophy which characterize his work.... Acutely observant in his method, Lampman created out of the minutiae of nature careful compositions of color, sound, and subtle movement. Evocatively rich, his poems are frequently sustained by a mood of revery and withdrawal, while their themes are those of beauty, wisdom, and reassurance, which the poet discovered in his contemplation of the changing seasons and the harmony of the countryside.” The Canadian Encyclopedia calls his poems “for the most part close-packed melancholy meditations on natural objects, emphasizing the calm of country life in contrast to the restlessness of city living. Limited in range, they are nonetheless remarkable for descriptive precision and emotional restraint. Although characterized by a skilful control of rhythm and sound, they tend to display a sameness of thought.” “Lampman wrote more than 300 poems in this last period of his life, although scarcely half of these were published prior to his death. For single poems or groups of poems he found outlets in the literary magazines of the day: in Canada, chiefly the Week; in the United States, Scribner’s Magazine, The Youth’s Companion, the Independent, the Atlantic Monthly, and Harper’s Magazine. In 1888, with the help of a legacy left to his wife, he published Among the millet and other poems," his first book, at his own expense. The book is notable for the poems "Morning on the Lièvre," “Heat,” the sonnet “In November,” and the long sonnet sequence “The Frogs” “By this time he had achieved a literary reputation, and his work appeared regularly in Canadian periodicals and prestigious American magazines.... In 1895 Lampman was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and his second collection of poems, Lyrics of Earth, was brought out by a Boston publisher.” The book was not a success. “The sales of Lyrics of Earth were disappointing and the only critical notices were four brief though favourable reviews. In size, the volume is slighter than Among the Millet—twenty-nine poems in contrast to forty-eight—and in quality fails to surpass the earlier work.” (Lyrics does, though, contain some of Lampman’s most beautiful poems, such as “After Rain” and “The Sun Cup.”) “A third volume, Alcyone and other poems, in press at the time of his death” in 1899, showed Lampman starting to move in new directions, with the nature verses interspersed with philosophical poetry like “Voices of Earth” and “The Clearer Self” and poems of social criticism like “The City” and what may be his best-known poem, the dystopian vision of “The City of the End of Things.” “As a corollary to his preoccupation with nature,” notes the Gale Encyclopedia, "Lampman [had] developed a critical stance toward an emerging urban civilization and a social order against which he pitted his own idealism. He was an outspoken socialist, a feminist, and a social critic." Canadian critic Malcolm Ross wrote that “in poems like 'The City at the End of Things’ and 'Epitaph on a Rich Man’ Lampman seems to have a social and political insight absent in his fellows.” However, Lampman died before Alcyone appeared, and it "was held back by Scott (12 specimen copies were printed posthumously in Ottawa in 1899) in favour of a comprehensive memorial volume planned for 1900." The latter was a planned collected poems "which he was editing in the hope that its sale would provide Maud with some much-needed cash. Besides Alcyone, it included Among the Millet and Lyrics of Earth in their entirety, plus seventy-four sonnets Lampman had tried to publish separately, twenty-three miscellaneous poems and ballads, and two long narrative poems (“David and Abigail” and “The Story of an Affinity”)." Among the previously unpublished sonnets were some of Lampman’s finest work, including “Winter Uplands”, “The Railway Station,” and “A Sunset at Les Eboulements.” “Published by Morang & Company of Toronto in 1900," The Poems of Archibald Lampman "was a substantial tome—473 pages—and ran through several editions. Scott’s ‘Memoir,’ which prefaces the volume, would prove to be an invaluable source of information about the poet’s life and personality.” Scott published one further volume of Lampman’s poetry, At the Long Sault and Other Poems, in 1943– “and on this occasion, as on other occasions previously, he did not hesitate to make what he felt were improvements on the manuscript versions of the poems.” The book is remarkable mainly for its title poem, "At the Long Sault: May 1660," a dramatic retelling of the Battle of Long Sault, which belongs with the great Canadian historical poems. It was co-edited by E.K. Brown, who the same year published his own volume On Canadian Poetry: a book that was a major boost to Lampman’s reputation. Brown considered Lampman and Scott the top Confederation Poets, well ahead of Roberts and Carman, and his view came to predominate over the next few decades. Lampman never considered himself more than a minor poet, as he once confessed in a letter to a friend: “I am not a great poet and I never was. Greatness in poetry must proceed from greatness of character—from force, fearlessness, brightness. I have none of those qualities. I am, if anything, the very opposite, I am weak, I am a coward, I am a hypochondriac. I am a minor poet of a superior order, and that is all.” However, others’ opinion of his work has been higher than his own. Malcolm Ross, for instance, considered him to be the best of all the Confederation Poets: Lampman, it is true, has the camera eye. But Lampman is no mere photographer. With Scott (and more completely than Scott), he has, poetically, met the demands of his place and his time.... Like Roberts (and more intensively than Roberts), he searches for the idea.... Ideas are germinal for him, infecting the tissue of his thought.... Like the existentialist of our day, Lampman is not so much 'in search of himself’ as engaged strenuously in the creation of the self. Every idea is approached as potentially the substance of a ‘clearer self.’ Even landscape is made into a symbol of the deep, interior processes of the self, or is used... to induce a settling of the troubled surfaces of the mind and a miraculous transparency that opens into the depths. Recognition Lampman was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1895. He was designated a Person of National Historic Significance in 1920. A literary prize, the Archibald Lampman Award, is awarded annually by Ottawa-area poetry magazine Arc in Lampman’s honour. Since 1999, the annual “Archibald Lampman Poetry Reading” has brought leading Canadian poets to Trinity College, Toronto, under the sponsorship of the John W. Graham Library and the Friends of the Library, Trinity College. His name is also carried on in the town of Lampman, Saskatchewan, a small community of approximately 730 people, situated near the City of Estevan. Canada Post issued a postage stamp in his honour on July 7, 1989. The stamp depicts Lampman’s portrait on a backdrop of nature. Canadian singer/songwriter Loreena McKennitt adapted Lampman’s poem “Snow” as a song, writing original music while keeping as the lyrics the poem verbatim. This adaptation appears on McKennitt’s album To Drive the Cold Winter Away (1987) and also in a different version on her EP, A Winter Garden: Five Songs for the Season (1995). Publications Poetry * Lampman, Archibald (1888). Among the Millett, and Other Poems. Ottawa, Ontario: J. Durie and son. * Lampman, Archibald (1895). Lyrics of Earth. Boston, Massachusetts: Copeland & Day. * Lampman, Archibald; Scott, Duncan Campbell (1896). “Two poems”. privately issued to their friends at Christmastide: not published. * Lampman, Archibald (1899). Alcyone and Other Poems. Ottawa, Ontario: Ogilvy. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1900). The Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto, Ontario: Morang. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1925). Lyrics of Earth: Sonnets and Ballads. Toronto, Ontario: Musson. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1943). At the Long Sault and Other New Poems. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. * Scott, Duncan Campbell, ed. (1947). Selected Poems of Archibald Lampman. Toronto, Ontario: Ryerson. * Coulby Whitridge, Margaret, ed. (1975). Lampman’s Kate: Late Love Poems of Archibald Lampman. Ottawa, Ontario: Borealis. ISBN 978-0-9195-9436-4. * Coulby Whitridge, Margaret, ed. (1976). Lampman’s Sonnets: The Complete Sonnets of Archibald Lampman. Ottawa, Ontario: Borealis. ISBN 978-0-919594-50-0. * Bentley, D.M.R., ed. (1986). The Story of an Affinity. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. ISBN 978-0-921243-00-7. * Gnarowski, Michael, ed. (1990). Selected Poetry of Archibald Lampman. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-919662-15-5. Prose * Bourinot, Arthur S., ed. (1956). Archibald Lampman’s letters to Edward William Thomson (1890-1898). Ottawa, Ontario: Arthur S. Bourinot Publisher. * Davies, Barrie, ed. (1975). Archibald Lampman: Selected Prose. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-9196-6254-4. * Davies, Barrie, ed. (1979). At the Mermaid Inn: Wilfred Campbell, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott in the Globe 1892–93. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2299-5. * Lynn, Helen, ed. (1980). An annotated edition of the correspondence between Archibald Lampman and Edward William Thomson, 1890-1898. Ottawa, Ontario: Tecumseh. ISBN 978-0-919662-77-3. * Bentley, D.M.R., ed. (1996). The Essays and Reviews of Archibald Lampman. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. * Bentley, D.M.R., ed. (1999). The Fairy Tales of Archibald Lampman. London, Ontario: Canadian Poetry Press. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archibald_Lampman

The Split Man sculpture represents the mental state of the dysfunctional human (here represented as a 30 year old). This human (male or female) is falling apart because he/she cannot or will not dedicate his or her life to one goal, consequently can’t create his/her true self, and, by failing to apply that true self, achieve self-realization. Failure to make the goal a reality results in en-darkenment, to wit, (energy) depression. Achievement of the goal results in en-lightenment, to wit, (energy) elation, and the experience of rapturous joy. The Split Man wants to die, in fact, needs to die. He/she needs to return to his/her original state in order to recover his/her essential self, therefore his or her unique life purpose (read: dharma). It’s the 100% application of life purpose (or dharma) that leads to the experience of the true self. Split Man, Victoria’s Way, Co Wicklow Ireland

Philip Levine (January 10, 1928– February 14, 2015) was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American poet best known for his poems about working-class Detroit. He taught for more than thirty years in the English department of California State University, Fresno and held teaching positions at other universities as well. He served on the Board of Chancellors of the Academy of American Poets from 2000 to 2006, and was appointed Poet Laureate of the United States for 2011–2012. Biography Philip Levine grew up in industrial Detroit, the second of three sons and the first of identical twins of Jewish immigrant parents. His father, Harry Levine, owned a used auto parts business, his mother, Esther Priscol (Prisckulnick) Levine, was a bookseller. When Levine was five years old, his father died. While growing up, he faced the anti-Semitism embodied by Father Coughlin, the pro-Nazi radio priest. Levine started to work in car manufacturing plants at the age of 14. Detroit Central High School graduated him in 1946 and he went to college at Wayne University (now Wayne State University) in Detroit, where he began to write poetry, encouraged by his mother, to whom he dedicated the book of poems, The Mercy. Levine earned his A.B. in 1950 and went to work for Chevrolet and Cadillac in what he called “stupid jobs.” He married his first wife, Patty Kanterman, in 1951. The marriage lasted until 1953. In 1953, he attended the University of Iowa without registering, studying with, among others, poets Robert Lowell and John Berryman, the latter of whom Levine called his “one great mentor.” In 1954, he earned a mail-order masters degree with a thesis on John Keats’ “Ode to Indolence,” and married actress Frances J. Artley. He returned to the University of Iowa teaching technical writing, completing his Master of Fine Arts degree in 1957. The same year, he was awarded the Jones Fellowship in Poetry at Stanford University. In 1958, he joined the English department at California State University in Fresno, where he taught until his retirement in 1992. He also taught at many other universities, among them New York University as Distinguished Writer-in-Residence, Columbia, Princeton, Brown, Tufts, and the University of California at Berkeley. Levine and his wife had made their homes in Fresno and Brooklyn. He died of pancreatic cancer on February 14, 2015, age 87. Work The familial, social, and economic world of twentieth-century Detroit is one of the major subjects of Levine’s life work. His portraits of working class Americans and his continuous examination of his Jewish immigrant inheritance (both based on real life and described through fictional characters) has left a testimony of mid-twentieth century American life. Levine’s working experience lent his poetry a profound skepticism with regard to conventional American ideals. In his first two books, On the Edge (1963) and Not This Pig (1968), the poetry dwells on those who suddenly become aware that they are trapped in some murderous processes not of their own making. In 1968, Levine signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse to make tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War. In his first two books, Levine was somewhat traditional in form and relatively constrained in expression. Beginning with They Feed They Lion, typically Levine’s poems are free-verse monologues tending toward trimeter or tetrameter. The music of Levine’s poetry depends on tension between his line-breaks and his syntax. The title poem of Levine’s book 1933 (1974) is an example of the cascade of clauses and phrases one finds in his poetry. Other collections include The Names of the Lost, A Walk with Tom Jefferson, New Selected Poems, and the National Book Award-winning What Work Is. On November 29, 2007 a tribute was held in New York City in anticipation of Levine’s eightieth birthday. Among those celebrating Levine’s career by reading Levine’s work were Yusef Komunyakaa, Galway Kinnell, E. L. Doctorow, Charles Wright, Jean Valentine and Sharon Olds. Levine read several new poems as well. Awards * 2013 Academy of American Poets Wallace Stevens Award * 2011 Appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (United States Poet Laureate) * 1995 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry– The Simple Truth (1994) * 1991 National Book Award for Poetry and Los Angeles Times Book Prize– What Work Is * 1987 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize from the Modern Poetry Association and the American Council for the Arts * 1981 Levinson Prize from Poetry magazine * 1980 Guggenheim Foundation fellowship * 1980 National Book Award for Poetry– Ashes: Poems New and Old * 1979 National Book Critics Circle Award– Ashes: Poems New and Old– 7 Years from Somewhere * 1978 Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize from Poetry * 1977 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets– The Names of the Lost (1975) * 1973 American Academy of Arts and Letters Award, Frank O’Hara Prize, Guggenheim Foundation fellowship Published works Poetry collections * News of the World, Random House, Inc., 2009, ISBN 978-0-307-27223-2 * Stranger to Nothing: Selected Poems, Bloodaxe Books, UK, 2006, ISBN 978-1-85224-737-9 * Breath Knopf, 2004, ISBN 978-1-4000-4291-3; reprint, Random House, Inc., 2006, ISBN 978-0-375-71078-0 * The Mercy, Random House, Inc., 1999, ISBN 978-0-375-70135-1 * Unselected Poems, Greenhouse Review Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-9655239-0-5 * The Simple Truth, Alfred A. Knopf, 1994, ISBN 978-0-679-43580-8; Alfred A. Knopf, 1996, ISBN 978-0-679-76584-4 * What Work Is, Knopf, 1992, ISBN 978-0-679-74058-2 * New Selected Poems, Knopf, 1991, ISBN 978-0-679-40165-0 * A Walk With Tom Jefferson, A.A. Knopf, 1988, ISBN 978-0-394-57038-9 * Sweet Will, Atheneum, 1985, ISBN 978-0-689-11585-1 * Selected Poems, Atheneum, 1984, ISBN 978-0-689-11456-4 * One for the Rose, Atheneum, 1981, ISBN 978-0-689-11223-2 * 7 Years From Somewhere, Atheneum, 1979, ISBN 978-0-689-10974-4 * Ashes: Poems New and Old, Atheneum, 1979, ISBN 978-0-689-10975-1 * The Names of the Lost, Atheneum, 1976 * 1933, Atheneum, 1974, ISBN 978-0-689-10586-9 * They Feed They Lion, Atheneum, 1972 * Red Dust (1971) * Pili’s Wall, Unicorn Press, 1971; Unicorn Press, 1980 * Not This Pig, Wesleyan University Press, 1968, ISBN 978-0-8195-2038-8; Wesleyan University Press, 1982, ISBN 978-0-8195-1038-9 * On the Edge (1963) Essays * The Bread of Time (1994) Translations * Off the Map: Selected Poems of Gloria Fuertes, edited and translated with Ada Long (1984) * Tarumba: The Selected Poems of Jaime Sabines, edited and translated with Ernesto Trejo (1979) Interviews * Don’t Ask, University of Michigan Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0-472-06327-7 * Moyers & Company, on December 29, 2013, Philip Levine reads some of his poetry and explores how his years working on Detroit’s assembly lines inspired his poetry. * “Interlochen Center for the Arts”, Interview with Interlochen Arts Academy students on March 17, 1977. References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Levine_(poet)

I love poetry. I write poetry based on my experience in life and love and the songs I listen to. I first started writing for school, but I'm literally addicted to poetry now. It's my escape. I have been through so many things in my life I should not have had to go through, especially since I'm only 14. But it all comes out in my poetry. I love watching crime shows like Criminal Minds and NCIS. I'm obsessed with TV news reports about such things as crime, train derailments, car accidents, and fires. It's just the way I am. They say music, especially rock music, takes away your pain, whether it be physical, emotional, spiritual, or mental. I learned it's not true. It just makes it better temporarily, but then makes it worse.