Anne Killigrew (1660–1685) was an English poet. Born in London, Killigrew is perhaps best known as the subject of a famous elegy by the poet John Dryden entitled To The Pious Memory of the Accomplish’d Young Lady Mrs. Anne Killigrew (1686). She was however a skilful poet in her own right, and her Poems were published posthumously in 1686. Dryden compared her poetic abilities to the famous Greek poet of antiquity, Sappho. Killigrew died of smallpox aged 25. Early life and inspiration Anne Killigrew was born in early 1660, before the Restoration, at St. Martin’s Lane in London. Not much is known about her mother Judith Killigrew, but her father Dr. Henry Killigrew published several sermons and poems as well as a play called The Conspiracy. Her two paternal uncles were also published playwrights. Sir William Killigrew (1606–1695) published two collections of plays and Thomas Killigrew (1612–1683) not only wrote plays but built the theatre now known as Drury Lane. Her father and her uncles had close connections with the Stuart Court, serving Charles I, Charles II, and his Queen, Catherine of Braganza. Anne was made a personal attendant, before her death, to Mary of Modena, Duchess of York. Little is recorded about Anne’s education, but it is known that she kept up with her social class, and she received instruction in both poetry and painting in which she excelled. Her theatrical background added to her use of shifting voices in her poetry. In John Dryden’s Ode to Anne he points out that “Art she had none, yet wanted none. For Nature did that want supply” (Stanza V). Killigrew most likely got her education through studying the Bible, Greek mythology, and philosophy. Mythology was often expressed throughout her paintings and poetry. Inspiration for Killigrew’s poetry came from her knowledge of Greek myths and Biblical proverbs as well as from some very influential female poets who lived during the Restoration period: Katherine Philips and Anne Finch (also a maid to Mary of Modena at the same time as Killigrew). Mary of Modena encouraged the French tradition of precieuses (patrician women intellectuals) which pressed women’s participation in theatre, literature, and music. In effect, Killigrew was surrounded with a poetic feminist inspiration on a daily basis in Court: she was encompassed by strong intelligent women who encouraged her writing career as much as their own. With this motivation came a short book of only thirty-three poems published soon after her death by her father. It was not abnormal for poets, especially for women, never to see their work published in their lifetime. Since Killigrew died at the young age of 25 she was only able to produce a small collection of poetry. In fact, the last three poems were only found among her papers and it is still being debated about whether or not they were actually written by her. Inside the book is also a self painted portrait of Anne and the Ode by family friend and poet John Dryden. The Poet and the Painter Anne Killigrew excelled in multiple media, which was noted by contemporary poet, mentor, and family friend, John Dryden in his dedicatory ode to Killigrew. He addresses her as "the Accomplisht Young LADY Mrs Anne Killigrew, Excellent in the two Sister-Arts of Poësie, and Painting." Scholars believe that Kelligrew painted a total of 15 paintings; however, only four are known to exist today. Many of her paintings display biblical and mythological imagery. Yet, Killigrew was also skilled at portraits, and her works include a self-portrait and a portrait of James, Duke of York. Some of her poetry references her own paintings, such as her poem “On a Picture Painted by her self, representing two Nimphs of DIANA’s, one in a posture to Hunt, the other Batheing.” Both her poems and her paintings place emphasis on women and nature, suggesting female rebellion in a male-dominated society. Contemporary critics noted her exceptional skill in both mediums, with John Dryden addressing his dedicatory John Dryden and critical reception Killigrew is best known for being the subject of John Dryden’s famous, extolling ode, which praises Killigrew for her beauty, virtue, and literary talent. However, Dryden was one of several contemporary admirers of Killigrew, and the posthumous collection of her work published in 1686 included several additional poems commending her literary merit, irreproachable piety, and personal charm. Nonetheless, critics often disagree about the nature of Dryden’s ode: some believe his praise to be too excessive, and even ironic. These individuals condemn Killigrew for using well worn and conventional topics, such as death, love, and the human condition, in her poetry and pastoral dialogues. In fact, Alexander Pope, a prominent critic, as well as the leading poet of the time, labelled her work “crude” and “unsophisticated.” As a young poet who had only distributed her work via manuscript prior to her death, it is possible that Killigrew was not ready to see her work published so soon. Some say Dryden defended all poets because he believed them to be teachers of moral truths; thus, he felt Killigrew, as an inexperienced yet dedicated poet, deserved his praise. However, Anthony Wood in his 1721 essay defends Dryden’s praise, confirming that Killigrew “was equal to, if not superior” to any of the compliments lavished upon her. Furthermore, Wood asserts that Killigrew must have been well received in her time, otherwise “her Father would never have suffered them to pass the Press” after her death. Authorship controversy Then, there is the question of the last three poems that were found among her papers. They seem to be in her handwriting, which is why Killigrew’s father added them to her book. The poems are about the despair the author has for another woman, and could possibly be autobiographical if they are in fact by Killigrew. Some of her other poems are about failed friendships, possibly with Anne Finch, so this assumption may have some validity. An early death Killigrew died of smallpox on 16 June 1685, when she was only 25 years old. She is buried in the Chancel of the Savoy Chapel (dedicated to St John the Baptist) where a monument was built in her honour, but has since been destroyed by a fire.

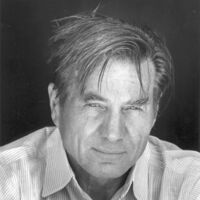

Galway Kinnell (February 1, 1927 – October 28, 2014) was an American poet. For his 1982 Selected Poems he won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and split the National Book Award for Poetry with Charles Wright. From 1989 to 1993 he was poet laureate for the state of Vermont. An admitted follower of Walt Whitman, Kinnell rejects the idea of seeking fulfillment by escaping into the imaginary world. His best-loved and most anthologized poems are "St. Francis and the Sow" and "After Making Love We Hear Footsteps". Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Kinnell said that as a youth he was turned on to poetry by Edgar Allan Poe and Emily Dickinson, drawn to both the musical appeal of their poetry and the idea that they led solitary lives. The allure of the language spoke to what he describes as the homogeneous feel of his hometown, Pawtucket, Rhode Island. He has also described himself as an introvert during his childhood. Kinnell studied at Princeton University, graduating in 1948 alongside friend and fellow poet W.S. Merwin. He received his master of arts degree from the University of Rochester. He traveled extensively in Europe and the Middle East, and went to Paris on a Fulbright Fellowship. During the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States caught his attention. Upon returning to the US, he joined CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and worked on voter registration and workplace integration in Hammond, Louisiana. This effort got him arrested. In 1968, he signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War. Kinnell draws upon both his involvement with the civil rights movement and his experiences protesting against the Vietnam War in his book-long poem The Book of Nightmares. From 1989 to 1993 he was poet laureate for the state of Vermont. Kinnell was the Erich Maria Remarque Professor of Creative Writing at New York University and a Chancellor of the American Academy of Poets. As of 2011 he was retired and resided at his home in Vermont until his death in October of 2014 from leukemia. Work While much of Kinnell's work seems to deal with social issues, it is by no means confined to one subject. Some critics have pointed to the spiritual dimensions of his poetry, as well as the nature imagery present throughout his work. “The Fundamental Project of Technology” deals with all three of those elements, creating an eerie, chant-like and surreal exploration of the horrors atomic weapons inflict on humanity and nature. Sometimes Kinnell utilizes simple and brutal images (“Lieutenant! / This corpse will not stop burning!” from “The Dead Shall be Raised Incorruptible”) to address his anger at the destructiveness of humanity, informed by Kinnell’s activism and love of nature. There’s also a certain sadness in all of the horror—“Nobody would write poetry if the world seemed perfect.” There’s also optimism and beauty in his quiet, ponderous language, especially in the large role animals and children have in his later work (“Other animals are angels. Human babies are angels”), evident in poems such as “Daybreak” and “After Making Love We Hear Footsteps”. In addition to his works of poetry and his translations, Kinnell published one novel (Black Light, 1966) and one children's book (How the Alligator Missed Breakfast, 1982). Kinnell wrote two elegies for his close friend, the poet James Wright, upon the latter's death in 1980. They appear in From the Other World: Poems in Memory of James Wright. References Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galway_Kinnell

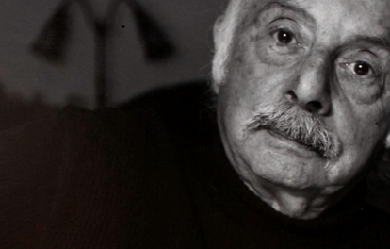

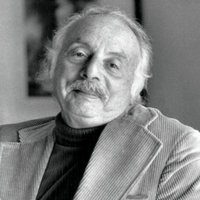

Stanley Jasspon Kunitz (July 29, 1905 – May 14, 2006) was an American poet. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress twice, first in 1974 and then again in 2000. Biography Kunitz was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, the youngest of three children, to Yetta Helen (née Jasspon) and Solomon Z. Kunitz, both of Jewish Russian Lithuanian descent.His father, a dressmaker of Russian Jewish heritage, committed suicide in a public park six weeks before Stanley was born. After going bankrupt, he went to Elm Park in Worcester, and drank carbolic acid. His mother removed every trace of Kunitz’s father from the household. The death of his father would be a powerful influence of his life.Kunitz and his two older sisters, Sarah and Sophia, were raised by his mother, who had made her way from Yashwen, Kovno, Lithuania by herself in 1890, and opened a dry goods store. Yetta remarried to Mark Dine in 1912. Yetta and Mark filed for bankruptcy in 1912 and then were indicted by the U.S. District Court for concealing assets. They pleaded guilty and turned over USD$10,500 to the trustees. Mark Dine died when Kunitz was fourteen, when, while hanging curtains, he suffered a heart attack.At fifteen, Kunitz moved out of the house and became a butcher’s assistant. Later he got a job as a cub reporter on The Worcester Telegram, where he would continue working during his summer vacations from college.Kunitz graduated summa cum laude in 1926 from Harvard College with an English major and a philosophy minor, and then earned a master’s degree in English from Harvard the following year. He wanted to continue his studies for a doctorate degree, but was told by the university that the Anglo-Saxon students would not like to be taught by a Jew.After Harvard, he worked as a reporter for The Worcester Telegram, and as editor for the H. W. Wilson Company in New York City. He then founded and edited Wilson Library Bulletin and started the Author Biographical Studies. Kunitz married Helen Pearce in 1930; they divorced in 1937. In 1935 he moved to New Hope, Pennsylvania and befriended Theodore Roethke. He married Eleanor Evans in 1939; they had a daughter Gretchen in 1950. Kunitz divorced Eleanor in 1958.At Wilson Company, Kunitz served as co-editor for Twentieth Century Authors, among other reference works. In 1931, as Dilly Tante, he edited Living Authors, a Book of Biographies. His poems began to appear in Poetry, Commonweal, The New Republic, The Nation, and The Dial. During World War II, he was drafted into the Army in 1943 as a conscientious objector, and after undergoing basic training three times, served as a noncombatant at Gravely Point, Washington in the Air Transport Command in charge of information and education. He refused a commission and was discharged with the rank of staff sergeant.After the war, he began a peripatetic teaching career at Bennington College (1946–1949; taking over from his friend Roethke). He subsequently taught at the State University of New York at Potsdam (then the New York State Teachers College at Potsdam) as a full professor (1949-1950; summer sessions through 1954), the New School for Social Research (lecturer; 1950-1957), the University of Washington (visiting professor; 1955-1956), Queens College (visiting professor; 1956-1957), Brandeis University (poet-in-residence; 1958-1959) and Columbia University (lecturer in the School of General Studies; 1963-1966) before spending 18 years as an adjunct professor of writing at Columbia’s School of the Arts (1967-1985). Throughout this period, he also held visiting appointments at Yale University (1970), Rutgers University–Camden (1974), Princeton University (1978) and Vassar College (1981).After his divorce from Eleanor, he married the painter and poet Elise Asher in 1958. His marriage to Asher led to friendships with artists like Philip Guston and Mark Rothko.Kunitz’s poetry won wide praise for its profundity and quality. He was the New York State Poet Laureate from 1987 to 1989. He continued to write and publish until his centenary year, as late as 2005. Many consider that his poetry’s symbolism is influenced significantly by the work of Carl Jung. Kunitz influenced many 20th-century poets, including James Wright, Mark Doty, Louise Glück, Joan Hutton Landis, and Carolyn Kizer. For most of his life, Kunitz divided his time between New York City and Provincetown, Massachusetts. He enjoyed gardening and maintained one of the most impressive seaside gardens in Provincetown. There he also founded Fine Arts Work Center, where he was a mainstay of the literary community, as he was of Poets House in Manhattan. He was awarded the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience award in Sherborn, Massachusetts in October 1998 for his contribution to the liberation of the human spirit through his poetry.He died in 2006 at his home in Manhattan. He had previously come close to death, and reflected on the experience in his last book, a collection of essays, The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden. Poetry Kunitz’s first collection of poems, Intellectual Things, was published in 1930. His second volume of poems, Passport to the War, was published fourteen years later; the book went largely unnoticed, although it featured some of Kunitz’s best-known poems, and soon fell out of print. Kunitz’s confidence was not in the best of shape when, in 1959, he had trouble finding a publisher for his third book, Selected Poems: 1928-1958. Despite this unflattering experience, the book, eventually published by Little Brown, received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. His next volume of poems would not appear until 1971, but Kunitz remained busy through the 1960s editing reference books and translating Russian poets. When twelve years later The Testing Tree appeared, Kunitz’s style was radically transformed from the highly intellectual and philosophical musings of his earlier work to more deeply personal yet disciplined narratives; moreover, his lines shifted from iambic pentameter to a freer prosody based on instinct and breath—usually resulting in shorter stressed lines of three or four beats. Throughout the 70s and 80s, he became one of the most treasured and distinctive voices in American poetry. His collection Passing Through: The Later Poems won the National Book Award for Poetry in 1995. Kunitz received many other honors, including a National Medal of Arts, the Bollingen Prize for a lifetime achievement in poetry, the Robert Frost Medal, and Harvard’s Centennial Medal. He served two terms as Consultant on Poetry for the Library of Congress (the precursor title to Poet Laureate), one term as Poet Laureate of the United States, and one term as the State Poet of New York. He founded the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and Poets House in New York City. Kunitz also acted as a judge for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition. Library Bill of Rights Kunitz served as editor of the Wilson Library Bulletin from 1928 to 1943. An outspoken critic of censorship, in his capacity as editor, he targeted his criticism at librarians who did not actively oppose it. He published an article in 1938 by Bernard Berelson entitled “The Myth of Library Impartiality”. This article led Forrest Spaulding and the Des Moines Public Library to draft the Library Bill of Rights, which was later adopted by the American Library Association and continues to serve as the cornerstone document on intellectual freedom in libraries. Awards and honors * 2006 L.L. Winship/PEN New England Award, The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden Bibliography * * Poetry * The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden (2005) * The Collected Poems of Stanley Kunitz (NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000) * Passing Through, The Later Poems, New and Selected (NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1995)—winner of the National Book Award * Next-to-Last Things: New Poems and Essays (1985) * The Wellfleet Whale and Companion Poems * The Terrible Threshold * The Coat without a Seam * The Poems of Stanley Kunitz (1928–1978) (1978) * The Testing-Tree (1971) * Selected Poems, 1928-1958 (1958) * Passport to the War (1944) * Intellectual Things (1930)Other writing and interviews: * Conversations with Stanley Kunitz (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, Literary Conversations Series, 11/2013), Edited by Kent P. Ljungquist * A Kind of Order, A Kind of Folly: Essays and Conversations’ * Interviews and Encounters with Stanley Kunitz (Riverdale-on-Hudson, NY: The Sheep Meadow Press, 1995), Edited by Stanley MossAs editor, translator, or co-translator: * The Essential Blake * Orchard Lamps by Ivan Drach * Story under full sail by Andrei Voznesensky * Poems of John Keats * Poems of Akhmatova by Max Hayward References Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Kunitz

My full name is Zachary Jon Davis. I was born in Celebration, Florida. I am currently going into cosmetology but, my goal is to open up my own haunted house! The world of horror and scaring people is where my heart sits and where my heart wants to be. I have never really been someone who shared their work, but I am feeling more open to the idea of letting my work be seen by others. Though skeptical about how other people will view it. Who cares, baring your hearts work is something that everyone should try at least once right? Haiku's are really fun to write, and they are usually what I am writing. Though I do have a lot of AA BB rhyme schemes in my older work. I'd love to get back into writing newer styles! If you have any interest in my work then just feel free to message me here, or find a way to contact me! Have a wonderful day! -Kniixx

Roderick Watson Kerr was born on January 1st 1895 at Old Monklands in Lanarkshire. His father (also called Roderick) was a master watchmaker. The family moved to Dalkeith shortly after his birth, and then to Edinburgh, living first in Candlemaker Row and then, after the death of Kerr senior, to Salisbury Terrace. Kerr was educated at Boroughmuir and Heriot's schools and then attended Broughton Junior Student Centre for several years, where, jointly with John Gould, he edited the Broughton Magazine from 1910-1911. His predecessor in the role of editor had been Hugh MacDiarmid, who, like Kerr, had been under the guidance of George Ogilvie, the teacher who was to prove a catalyst for literary development. While continuing his education during the day, he had joined The Scotsman newspaper as an apprentice, and worked there in the evenings. After Broughton, Kerr enrolled for teacher training at the Edinburgh Professional Training College (which became Moray House) and there too, he edited the college magazine. Kerr enlisted in the army shortly after the outbreak of war. He was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Machine Gun Corps, and from there volunteered to work with the Army’s new weapon, the tank, joining the 2nd Royal Tank Corps after it was founded in 1916. He was awarded the Military Cross for his courage in commanding his tank in action in September 1918, despite being himself badly wounded. After a year in hospital, he was invalided out of the army in October 1919. After the war, Kerr attended classes at the University of Edinburgh, from 1921 to 1923, leaving to start work as a junior sub-editor at The Scotsman. While at university, Kerr formed a friendship with George Malcolm Thomson; between them, they planned the foundation of a new publishing house to accommodate and promote a new Scottish literary culture. The Porpoise Press started up in 1922. Its first production, launching the first series of contemporary writing in pamphlet form, was a collection of poems by F.V. Branford. The literary quality of the broadsheets was patchy, the editors finding it harder to get first-class writing to publish than they had anticipated. It wasn’t until Kerr’s own issue, No. 10 in 1924, that they came close to the satirical poetry designed to ‘rile the citizenry’ they had originally hoped for. But the stresses of running a small press took their toll, and both men, no longer students, had livings to make. Thomson moved to London in 1925; Kerr took a post as leader-writer on the Liverpool Daily Post & Echo, and left Edinburgh in 1926, but not before acknowledging the ‘spirit of joyous adventure’ which had filled the three years of their work (in a note appended to Thomson’s An Epistle to Roderick Watson Kerr (2nd series, No. 6). The Porpoise Press transferred to the guardianship of Lewis Spence. Kerr married Joan Macpherson from Kingussie in June 1927; they settled in Liverpool and enjoyed family life until 1939, when Mrs Kerr and the children were evacuated back to her parents’ farm in Kingussie, only returning in 1943 when the danger of bombing in Liverpool was over. Kerr’s job as sub-editor and leader writer with the Daily Post & Echo lasted until his retirement in 1957 – retirement taken early because of illness; he died in 1960. In an open reference written for Kerr in April 1914, George Ogilvie praised the ‘singular freshness and even originality of expression’ of his writing. Kerr kept a notebook during his active service in the war, with poems drafted in it; they were collected in War Daubs, published by John Lane in 1919. The publisher advertised the book as being the work of one who strips away the false glory of war and makes us look at it in all its nakedness. The Times Literary Supplement commented ‘The trench scenes are powerfully-etched impressions – vivid, intense, sincere', and a reviewer in the Sunday Evening Telegram said: 'Mr. Watson Kerr sees with the eyes of the man who has the brains to understand what it all means.' Hugh MacDiarmid included several of the war poems in the first issue of his anthology Northern Numbers (1920), and hoped for more, but in fact Kerr published very little poetry after the war. His own Porpoise Press pamphlets were satirical pieces; the first, Annus Mirabilis, or the Ascension o Jimmie Broon (1924), Alistair McCleery calls ‘clever humour aimed at obvious Aunt Sallies’. Kerr’s surviving son describes his father sitting daily in the park in the hours before his evening stint at the newspaper in Liverpool, tinkering with another long poem, again of social and political satire, but Kerr’s only other major literary publication was Style of Me: letters of Eula from the U.S.A., in 1945. Hugh MacDiarmid, in The National Outlook in 1921, wrote that Kerr’s war poetry was ‘the best produced by any Scottish soldier’, and it is for the war poems and his part in the founding of The Porpoise Press that Roderick Watson Kerr will be remembered. References http://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poetry/poets/roderick-watson-kerr

When the world seems to go unfair, I use my poetry as my only escape. When my pen hits the paper I'am in a whole different world. I write about whatever im feeling at the moment. All my poetry rhymes, and it all comes from something ive went through or am currently dealing with. PLEASE feel free to comment your thoughts.

I have always been captivated by the beauty of poetry; the elegance and clarity with which such pain and intensity can be translated. Identifying with a poem is different than relating to plain words, it connects you not only to someone's inner self but also to their creative ability. I started writing poetry in elementary school (I should probably burn those poems) and mostly wrote about nature, since as a kid I did not have many troubles. As I grew older, though, my poetry transformed into a channel for my painful experiences and trauma. At 17, my twin brother, Christopher, committed suicide. I found bleeding myself dry onto paper with the feelings and thoughts I could not comprehend inside my own mind helped me to sort through the shock, the pain, and the regret. Four years later, my father died in my arms from a heart attack. Again, I was faced with internal anguish, boiling under my skin and reverberating off the walls of my consciousness. Poetry has always been my outlet. I am not talented at drawing or really any other art form. Translating very dark, personal pain, into rhythmic, flowing stanzas allows me to open up in ways I cannot otherwise.

Everyone's entitled to their art; here is mine. Everyone has a lot to process in life and should be able to share the product that results from that construction of meaning. But here it is. Pieces I've written over time and I don't have to tell you explicitly how they all fit together. The whole story is there, but you don't have to understand it like I do. It's for both of us.

I welcome you to my place where you'll find my inter most feelings expressed through my poetry. And through my writings I invite you to enjoy and discover a little more about my life. I started writing when I was in my early teens, without having previous knowledge of life's challenges. I found out very early that if one really wants to progress, you will discover answers for yourself. To me my style of writing is unique, mainly because it comes from deep within my heart. I consider my words a mixture of emotions and thoughts of my spirit and life, written in the form of poetry. Through this web site I hope to share with you a little of the pleasures I enjoy so much. And through my poetry I hope to capture a bit of your interest. When I write I try to portrait my inspirations and my feelings and through my poetry I find answers. If I'm really lucky my poetry finds it's way to paper. For this reason I invite you to share with me a walk through my words.

I'm a 19 year old college student. My smile is a lie and hides many unpleasant thoughts. Having dealt with depression in the past and currently struggling with self harm and what some might call an eating disorder, I live a different life than many. I have recently started writing poems with the hope of releasing my negative feelings. Feedback is appreciated. Hope you enjoy what I've written.

I know. In most of my poems I sound dark and moody and like I live in black skinny jeans and a hoodie. But no, I'm not as depressed as I sound. I am, in fact, a relatively optimistic person with a rather positive outlook on life. I love my God and He loves me, so that gets me through the tough times. In those tough times, though, I shut down. It's not healthy, but I tend to unintentionally, and usually unawaredly (is that a word? Meh. Sounds good.), internalize my feelings to the point of not believing they're even there. Sometimes, though, I wind up unable to sleep and staring at the ceiling because of the dark thoughts swarming through my head. Those nights, I write. Anytime I have a rough patch of emotions, I write it down, make it pretty and usually rhyming, and call it a day. These poems are the less personal (yeah. Less personal.) ones that I wanted to share. Thank you for visiting my page and God bless. K

I'm 21 I have been writing since I was in the 7th grade but I was too scared to share them with anyone, I'm married but going through a divorice and I have a 2 year old daugher who is the best blessing in my life and is my world. I love photography. I love the out doors. I want to major in Kids Psychology. I love Family Guy and American Dad or anything with Adam Sandler. I have a cat named Thrall lol from WoW, I love to read all the time. I see the beauty in everything no matter how ugly it may seem, beauty is in the eyes of the beholder.